Site on the Gettysburg Battlefield

Image: Nicholas Codori Farm

Image: Nicholas Codori Farm

Emmitsburg Road

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

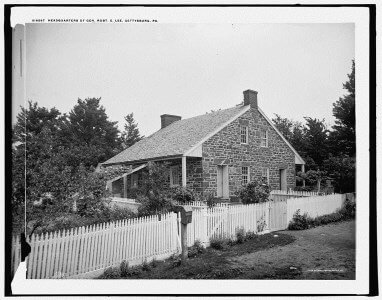

The heaviest fighting at the Battle of Gettysburg took place around the buildings and in the fields and orchards of the area’s farms owned by people whose lives were forever changed in July 1863. The Nicholas Codori Farm is on the east side of Emmitsburg Road just south of Gettysburg. The farmhouse is the same, except for the two story brick addition added in 1877. The current barn is a replacement for the original which was torn down in 1882.

Before the Battle

Nicholas Codori came to Gettysburg from Alsace, France, in 1828 at the age of 19, and apprenticed himself to Anthony B. Kuntz to learn the butchering business. Codori became the wealthiest and best known butcher in town. He had 11 children and a thriving business, and needed more room.

In 1843, Codori purchased the home at 44 York Street, one of the oldest and finest houses in town. He later bought the property on either side of the house, building a large carriage house at the back of the east side and adding his meat market to the west side. This is where his family lived until his death in the 1870s.

As Nicholas Codori prospered, he invested much of his money in real estate. He bought the 273 acre Codori farm in 1854, replacing the original log house with today’s two story frame house. Codori lived in town and rented the farm to tenants. At the time of the battle it was occupied by his niece Catharine Codori Staub and her husband John Staub.

Located along the Emmitsburg Road about 400 yards in front of the Union battle lines on Cemetery Ridge, the Codori house spent most of the battle within the Union forward skirmish line. One of eight existing Pennsylvania bank barns in the Park, the Codori barn is a representative structure of a 19th century Pennsylvania farm.

July 1, 1863

Mid-morning on July 1, 1863, USA General John Reynolds and his I Corps rushed up the Emmitsburg Road to support General John Buford‘s Cavalry, which was barely holding CSA General Henry Heth‘s Infantry at bay on the Chambersburg Road northwest of Gettysburg.

The Union column contained 8,000 men and was several miles long. The famed ‘Iron Brigade’ was among the first to arrive in Gettysburg. As they approached the Codori Farm, they heard gunfire to their northwest and were ordered to move on the double quick across the Codori fields west of the road and up towards McPherson’s Ridge.

The Codori Farm was apparently occupied by Codori’s relatives on July 1 because an officer mentioned an ‘old man’ coming through the gate and requesting that the soldiers “not go through his wheat field.” Of course, they immediately crossed that field, heading east to Cemetery Ridge, where they reported to General Abner Doubleday. This is the only known mention of the Codori Farm on the first day of the battle.

The ‘old man’ could have been Anthony Codori – Nicholas Codori’s brother – out on the farm with his wife visiting their daughter Catherine Staub and his three young grandchildren. Interestingly, records show that on July 8, 1863, Catherine delivered twins, so it is understandable why she would need someone to be with her at that time.

Her husband John was away in the Federal army in Virginia with his regiment, the 165th Pennsylvania Infantry. It is not known where Catherine and her family went after July 1, but we can assume that they left, because no mention of civilians was made by the many soldiers who occupied the farm after that day.

The Nicholas Codori family hid in the basement of their York Street home during the street fighting on the afternoon of July 1, 1863, listening as bullets struck their home above them. For months after the battle the house served as the Catholic chapel since St. Francis Xavier Catholic Church was full of wounded soldiers.

July 2, 1863

By first light,the main body of the two armies had arranged themselves to the south of town along two ridges known as Seminary Ridge (Confederates) and Cemetery Ridge (Union),the area between being bisected by the Emmitsburg Road. The Union Army of the Potomac numbered 95,000 and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, 75,000.

General Robert E. Lee had determined that he would attack his enemy on both flanks simultaneously, with General Richard Ewell hitting the Union Army at Culp’s Hill on the right and General James Longstreet striking at Little Round Top on the left. Then he would order an en echelon attack up the Emmitsburg Road.

Ewell did nothing until the evening of that day, which was then too little and too late. Longstreet also delayed his attack, saying he would like to wait for Pickett’s Division, which had not yet arrived. Longstreet, affectionately known as ‘Old Pete’ by his men, initially was holding out for a defensive strategy, but could not convince Lee.

Union General Daniel Sickles, who remembered having to give up high ground the previous month at Chancellorsville, with disastrous consequences. Now, studying the terrain at his place at the end of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, Sickles decided there was better position on higher ground three-fourths of a mile in front of him at the Emmitsburg Road – and he determined to place his Third Corps there.

After requesting permission from General George G. Meade and receiving no positive reply, Sickles ordered his men forward anyway, creating a salient (a bulge) in this part of the line that could be attacked from all sides. Both of his flanks were now “in the air,” with his line beginning at Devil’s Den, running through John Sherfy’s peach orchard and ending at the Codori Farm.

Meade found out about Sickles’ movement forward at the same time that Longstreet’s artillery opened on Third Corps batteries in the Peach Orchard. There was nothing else for Meade to do for the moment but to order reinforcements forward to help Sickles. Many men would die trying to back up Sickles’ untenable position.

After a desperate struggle at Little Round Top and in the Wheatfield by Hood’s Division. General William Barksdale’s ferocious Mississippians were sent forward as part of Lee’s en echelon attack. The objective was to break through the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, the northern part of which was held by the II Corps commanded by General Winfield Scott Hancock.

The II Corps was stretched along the crest of the ridge, which also formed the eastern boundary of the Codori Farm. At six o’clock, Barksdale and his men rolled over the Federal troops in the Peach Orchard, unhinging the Union’s position from the Wheatfield to the center of their entire line, and ending up at Plum Run. Here, they where finally stopped, and General Barksdale was mortally wounded.

Now General Cadmus Wilcox and his Alabama Brigade hurried forward, threatening to push through a gap that had opened when Union troops there had moved off to the Wheatfield. Hancock ordered in the men of the small-in-number but seasoned 1st Minnesota, who crashed into the Alabamians. After 20 minutes of fighting, only 47 men were left standing, but they had delayed the Rebels long enough for Hancock to send in reinforcements to stop the rebel advance.

Next, it was General Ambrose Wright’s turn to hammer the Union line. Initially, he was successful, his brigade rolling over the Federals near the Codori house. Union soldiers had advanced to the road and prepared a defensive position by piling up a barricade of fence rails behind the road. They were surprised by the approach of Wright’s men, who were hidden from view by tall grass. Confusion reigned, and many men were taken prisoners.

As the day drew to a close, the armies were realigned on their respective ridges. In his report to General Lee, General Wright complained about the lack of support and freely stated that had he had that support “I should have been able to maintain my position on the heights.” Perhaps this reinforced Lee’s resolve to again attack across Codori’s fields the next day.

July 3, 1863

The day dawned hot and muggy. The Confederate cannonade began about 1 p.m. For nearly two hours, upwards of 120 guns battered Cemetery Ridge, answered by over 100 U.S. pieces. Many rounds went over the crest of the ridge where the Union men lay pressed to the ground, and wreaked havoc on the batteries, horses and equipment behind.

Union artillery responded more slowly, with fewer rounds, in order to conserve ammunition. Even so, the human damage done to the Confederate infantry was more costly. Many shells found their mark among the men of General George Pickett‘s Division who were waiting in battle order in Pitzer’s Woods.

At the end of the cannonade these Virginia veterans were to begin their three-quarter mile advance across the Codori farm and up Cemetery Ridge. Longstreet, feeling that the assault would fail but duty bound to follow Lee’s orders, regretfully ordered Pickett’s Division forward.

The Southerners passed on either side of the house as they moved toward the Union center. Their first objective was the Codori barn, which has three small cupolas on its roof. The Confederate soldiers used the barn as an orientation device. As they crossed the Emmitsburg Road, they were met with a terrific barrage of shot and shell.

Their final objective was a copse of trees on the crest of Cemetery Ridge at the rear of the Codori property. As the assault continued, and the men in gray got closer and closer to the wall, more and more Confederates were being wounded. Pickett’s division were eventually repulsed with great loss in their attempt to break the Union line.

In 1861 Nicholas Codori had purchased the 66-acre, pie-shaped piece of land west of the Emmitsburg Road. Today one corner of that plot is the site of the Virginia monument which is purportedly the place where General Lee watched Pickett’s division assault the Union center.

The Codori farm went from farmland to battlefield to burial ground in three days. After the wounded were removed the burials began. According to Wasted Valor by Gregory Coco, 583 Confederates were buried on this farm: men from Wright’s brigade who were killed here while attacking the Union center late on July 2 and those who were killed during Pickett’s Charge on July 3. More than on any other farm on the battlefield.

After the Battle

In 1868 Nicholas Codori sold his Emmitsburg Road farm. It was useless for farming purposes because it was now a mass grave for Confederate soldiers. However, by 1872, all of the remains that could be located were removed from the fields and shipped south and Codori bought the farm back. A rear addition to the brick farmhouse was built in 1877.

Nicholas Codori suffered a mowing accident in July 1878. An article from The Gettysburg Times entitled Shocking Accident tells the sad tale:

On Monday last Mr. Nicholas Codori, the well-known butcher of this place, met with a terrible accident from a mowing machine, which may prove fatal. After breakfast he hitched up a favorite young colt team on a spring wagon and drove out to his farm a short distance southwest of town intending to mow a field of grass, and transferred the colt team from the spring wagon to the mower. It was a sprightly team and had never been hitched to the mower.

The rattle of the machine frightened the team, which started to run, and Mr. Codori was thrown from his seat in front of or on the knives. Sometime after, probably a half an hour, Mr. Butt, the tenant, noticed the team and mower standing up in the orchard some distance from the grass field. He went over, secured the team and then went in search of Mr. Codori, who was found sitting in the grass, with his right foot severed from the leg immediately above the ankle, and shockingly cut and injured in the groin.

Strange to say, Mr. Codori was not only sensible, but showed self possession and composure, giving orders that he be driven to town and directing his missing foot to be brought with him. He was put in the spring wagon, and remained in a sitting posture, saluting with his usual pleasant greeting acquaintances met on the way. He directed the driver to drive to Dr. Horner’s, told the Doctor he had lost a leg and wanted his services at his residence.

The bones of the leg above the ankle, where the limb had been severed by the mower, being splintered, it was found necessary to amputate the leg below the knee. The wounds about the groin were also dressed. The latter are the most serious, and from them the most danger is apprehended. Not withstanding Mr. Codori’s vigorous constitution, his injuries are such as to excite grave apprehensions as to the results.

Nicholas Codori died of his injuries on July 11, 1878.

The Codori Farm, which witnessed the ushering of so many souls from this world to the next in July of 1863, is an American shrine. The farm was sold to Gettysburg National Military Park in 1907. Today it is owned by the National Park Service and the farmhouse is a residence for park personnel.

The battle veterans came back to Gettysburg for reunions in 1913 and 1938, and although they did not camp on the Codori Farm, a few of the hardier ones went there and recreated Pickett’s Charge. This time, however, instead of bullets greeting the Confederates as they approached the old stone wall, grizzled Union vets cheered them on and rewarded them with a handshake.

SOURCES

The Codori Farm

Draw the Sword: The Codori Farm

Action on or Around Codori’s Farm

From Farmland to Battlefield to Burial Ground in Three Days – PDF File