Wife of General John Buford

Martha (Pattie) McDowell Duke was born June 25,1830, in Georgetown, Scott County, Kentucky, to James and Mary Duke. She was the first cousin of the famed Confederate raider, CSA General Basil Duke, with whom she was raised, and a second cousin of USA General Irvin McDowell. Martha was also the granddaughter of the youngest sister of Chief Justice John Marshall. This means she was closely related to Thomas Jefferson and all the Virginia Randolphs. Her maternal grandfather was Colonel Abraham Buford, a Revolutionary War hero.

Martha (Pattie) McDowell Duke was born June 25,1830, in Georgetown, Scott County, Kentucky, to James and Mary Duke. She was the first cousin of the famed Confederate raider, CSA General Basil Duke, with whom she was raised, and a second cousin of USA General Irvin McDowell. Martha was also the granddaughter of the youngest sister of Chief Justice John Marshall. This means she was closely related to Thomas Jefferson and all the Virginia Randolphs. Her maternal grandfather was Colonel Abraham Buford, a Revolutionary War hero.

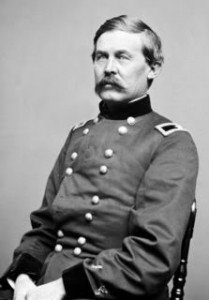

Image: General John Buford

John Buford, Jr. was born in Woodford County, Kentucky, March 4, 1826, the first child of his father’s second marriage to Anne Bannister. John’s family had a long martial tradition, dating back to the family’s roots in Ireland. John’s father was the son of a prominent Virginia veteran of the Revolutionary War, Simeon Buford. John’s mother was the daughter of Captain Edward Howe of the United States Navy.

John’s mother died in a cholera epidemic when he was only eight; by the time he was ten, his father had moved the family to the Illinois town of Stephenson, known today as Rock Island. In 1842, John’s father was elected state senator for Rock Island County, and in 1843 was commissioned appraiser of real estate belonging to the State Bank of Illinois. He would remain in public service for the rest of his life.

Growing up, John was athletic and fit, loved the outdoors, hunting and fishing. He enjoyed horseback riding on the dirt streets and possibly clerked in his father’s small grocery store on the Rock Island levee. He had two brothers, Thomas Jefferson Buford and James Monroe Buford, as well as a half brother and a half sister from his father’s first marriage.

Sixteen-year-old John Buford dreamed of attending the United States Military Academy at West Point, and applied for admission in 1842. His half-brother, Napoleon, had graduated from West Point in 1827. The War Department denied John’s application because policy did not allow two brothers to attend the Academy. The denial sparked a flurry of letter writing on John’s behalf, including one from Napoleon that stated, “[h]e has all of the qualities for making a good soldier, and is well prepared to enter in the course of studies at the Academy.”

John enrolled at Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, for the 1842-43 academic year. After completing one year there, he moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he resided with his half brother Napoleon and attended college. Napoleon again led a vigorous letter writing campaign, and John was finally accepted at West Point in 1844. He excelled in horsemanship and was a good problem solver.

John Buford graduated from West Point in 1848, ranking 16th in a class of 38. He developed close friendships with two future commanders and friends, Ambrose Burnside and George Stoneman. Other classmates who would become Civil War Generals include Fitz-John Porter, George B. McClellan, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and George Pickett. The class of 1847 included A.P. Hill and Henry Heth, two men Buford would face at Gettysburg on the morning of July 1, 1863.

After graduation from West Point, Buford started service in the 1st United States Dragoons as a brevet second lieutenant. The following year he went to the 2nd United States Dragoons. A dragoon uses a horse to get to and move about the battlefield, but he dismounts to fight. They were therefore trained in horse riding as well as infantry fighting skills. As a rule, Civil War cavalry fought while mounted. The Battle of Brandy Station was fought by mounted cavalry.

To Buford’s disappointment, the Mexican War ended before he had a chance to put his skills to the test. He would gain all of his experience on the American frontier fighting Indians, putting down rebellions, and shepherding supply trains over unforgiving terrain. In the field, Buford favored well-worn clothes, with a pipe and tobacco stashed in one pocket. He was promoted to second lieutenant in 1849 and to first lieutenant in 1853.

On May 9, 1854, Lieutenant John Buford married Martha McDowell Duke of Georgetown, a small village only ten miles from Buford’s boyhood home. She was called Pattie by friends and family. They had two children: James Duke Buford, born in July 1855, and Pattie McDowell Duke Buford, born October 1857. Pattie spent most of her time in Washington while John was away. Two-thirds of her married life was spent away from her husband, though she remained true to him.

During his dragoon service, Buford was in the Southwest and Texas. He served as quartermaster for the Second Dragoons from 1855 through August 1858, fighting in several Indian uprisings. While serving as quartermaster, he participated in quelling the disturbances in “Bleeding Kansas,” in 1856 and 1857. He fought the Sioux and was involved with peacekeeping assignments during the period of unrest known as Bleeding Kansas.

The Second Dragoons were then sent west under the command of Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston to participate in the Utah Expedition against Brigham Young and his Mormon followers during 1857 and 1858. Buford was promoted to captain on March 9, 1859, serving a brief stint of detached service in Washington, DC, and was then sent to frontier duty in Oregon. He served at Fort Crittenden, Utah, until the beginning of the Civil War.

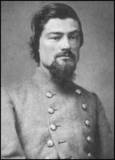

Buford in the Civil War

As the fear of secession became a reality, the Bufords, like many other American families, were deeply divided by the Civil War. John Buford’s older half brother, Napoleon Bonaparte Buford, graduated sixth in his class at West Point in 1827, and served in the Union Army during the Civil War, promoted to the rank of brevet major general by the end of the war. John’s first cousin, Abraham Buford, reached the rank of brigadier general in the Confederate Army, commanding a division of General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Buford was offered a commission in the Confederate army, which he rejected, saying, “I’ll live and die under the Union.” He and his regiment, the 2nd US Cavalry, traveled from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to Washington, DC, arriving in October 1861.

Buford’s Civil War career was slow getting started. Despite his experience as a cavalry officer, he was assigned to staff duty at the War Department as an assistant inspector general in November 1861. By then a major, he languished in this role until discovered there by General John Pope, with whom Buford had served in the old army.

Pope came to Washington to take command of the Army of Virginia, and was surprised to find Buford there in an unimportant staff job. Pope, who knew Buford well, rescued Buford from oblivion and ordered him to report for assignment to the Army of Virginia on July 27, 1862. Pope promoted Buford to brigadier general to replace one of his cavalry commanders, and assigned him to the command of the II Corps’ Cavalry Brigade.

Second Manassas Campaign

Buford first important contribution as a cavalry commander came at the Second Battle of Bull Run; it also represented the first time the blue cavalry stood up to General JEB Stuart in a toe-to-toe fight. Troopers from Buford’s command captured Stuart’s plumed hat during a surprise raid on his headquarters in the early phases of the campaign.

Buford fought with distinction at Manassas. He personally led a bold mounted charge on August 30, 1862, driving several regiments of Confederate cavalry before being routed by a counterattack. In the process, he was wounded in the knee. Although some Union newspapers reported that he had been killed, the injury was painful but not serious, and he had to go on sick leave, but not for long. His service during Second Manassas went largely unnoticed.

Buford learned from his experiences at Second Manassas: he had not committed his entire force in the fight and had ultimately lost as a result. He realized that mounted charges were not always the most effective means of employing cavalry, and recognized the importance of scouting and of the delaying effect that dismounted cavalry could have upon the advance of infantry. These lessons stuck with him, and he made good use of them throughout the remainder of his career.

During the winter of 1862-63, Buford moved his family to Washington, DC. Perhaps the high point of their season was the evening that his wife Pattie and his half brother Napoleon met President Abraham Lincoln at the White House. The lowest point certainly had to have been the night Buford was pick-pocketed of $2,000 in a local bar. Ironically, on the same day that the general lost his money, Union cavalry had fought ferociously at Kelly’s Ford and managed to kill Major John Pelham, the famed commander of Stuart’s Horse Artillery. Buford’s spirit seemed to be catching. For Union cavalry, the tide was about to turn.

Buford’s Cavalry Tactics

During the Antietam and Fredericksburg Campaigns, Buford acted as cavalry advisor to McClellan and Burnside. Buford made significant contributions to the Union efforts in the Eastern Theater. Instead of mounted, saber-reliant, heavy-cavalry tactics, he substituted the light-cavalry concept, which he had mastered while fighting against the Plains Indians. The dismounted cavalry (or Dragoon) tactics Buford used were the culmination of a method of fighting which he helped develop and propagate within the Union cavalry.

In February 1863, when General Joseph Hooker consolidated the cavalry into a corps, Buford returned to active duty in the command of the elite Reserve Brigade in the I Division, Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac. There he exercised his talents in teaching his troopers the advantages of fighting on foot rather than in the saddle. Although Buford performed well at Chancellorsville in May 1863, cavalry chief General George Stoneman’s abortive raid took him away from the important action.

When Stoneman was replaced soon after that miserable showing, Buford was considered as a replacement, but Hooker gave command of the Cavalry Corps to the flashier, more publicity-savvy General Alfred Pleasonton, although Hooker later agreed that Buford would have been the better choice. Buford was given a division, and he led his cavalry at Brandy Station, Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville during the spring of 1863, but he did not distinguish himself.

Marching from the Union camps near Fredericksburg, Virginia, in June, 1863, John Buford led his soldiers northward in an attempt to shadow the Confederate march into Maryland and Pennsylvania. Physically, Buford was still somewhat bothered by his knee wound, but as the Gettysburg Campaign developed in the following weeks, Buford was again energetic and invaluable in reconnaissance, providing information about the enemy that went entirely unappreciated by Pleasonton.

Colonel Theodore Lyman, who met Buford during the Gettysburg Campaign, gave the following description of Buford:

He is one of the best officers of [the Union cavalry] and is a singular-looking party… a compactly built man of middle height, with a tawny mustache and a little triangular gray eye, whose expression is determined, not to say sinister. His ancient corduroys are tucked into a pair of ordinary cowhide boots and his blue blouse is ornamented with holes; from one pocket thereof peeps a huge pipe, while the other is fat with a tobacco pouch.

Notwithstanding this get-up, he is a very soldierly looking man. He is of a good natured disposition but not to be trifled with. Caught a notorious spy last winter and hung him to the next tree, with this inscription: ‘This man is to hang three days; he who cuts him down before shall hang the remaining time.’

Another of his soldiers said Buford was “straightforward, honest, conscientious, full of good common sense, and always to be relied upon in any emergency… decidedly the best cavalry officer in the Army of the Potomac.” While no match for his rival JEB Stuart in flair, he was popular with his men.

By the time of the great battle he was 37 years old and one of the best Union cavalry officers. Perhaps most tellingly, Buford was known to his comrades as “Old Steadfast.” As demonstrated amply throughout the Gettysburg Campaign, his command was prepared to follow him anywhere and to do his bidding to the best of their ability. Few Union officers of the Civil War were blessed with better commands or with better subordinates to carry out their orders.

Buford at Gettysburg

The end of June found General Buford in a fateful location about ten miles south of Gettysburg, which lies in an area of foothills leading to South Mountain to the west. The area consists of a series of parallel ridges, undulating across the surrounding countryside. As General Robert E. Lee moved his spread-out Army of Northern Virginia across Pennsylvania in late June, the crossroads town of Gettysburg lay on his route of march; it was also in the path of General George G. Meade‘s Army of the Potomac.

The right wing of the Army of the Potomac was also approaching, and Buford’s orders were to cover the right wing’s left flank – Confederate forces were known to be in Cashtown, eight miles west – and to report all movements of the enemy immediately. The first to fully reach the field might win the major battle both armies were seeking. Buford’s cavalry got there first, and his orders from Pleasonton were clear: “Hold Gettysburg at all costs until supports arrive.”

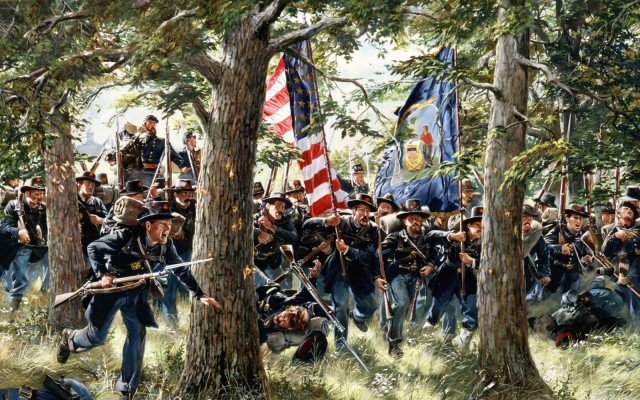

Image: Coming Rain

Image: Coming Rain

Dale Gallon, Artist

June 30, 1863, McPherson’s Farm

Brigadier General John Buford at Gettysburg

With brigade commanders Devin and Gamble

On the morning of June 30, Buford led two brigades of his cavalry and six pieces of artillery into Gettysburg, and approached the town just as his scouts spied a column of Confederate soldiers west of town. Buford decided to picket that area, and send a cavalry outpost west of Gettysburg to look for the Confederates if they returned the next day. He then sent a message to his old friend, General John Reynolds, commander of the Union First Corps, asking him to march to Gettysburg, and telling him that there were Confederates camped in the area.

Buford knew the bulk of Lee’s army was arriving from the west side of town, so he located strong defensive lines on the ridges to the west – with an excellent fall-back position on Cemetery Ridge to the rear. If his cavalry could slow down Lee’s advancing troops, the Federal army had a chance to hold the best high ground and win the coming battle.

On the evening of June 30, Buford deployed scouting parties in advance of the McPherson’s Ridge line. He also placed pickets along the Chambersburg Pike, well forward of the main line, anticipating the Confederate approach, thereby providing an early warning system. The pickets scattered themselves at intervals of thirty feet, using fence posts and rail fences as shelter.

At a meeting with his brigade commanders that night, Colonel Tom Devin, always spoiling for a fight, announced he would hold his position next day. Buford, ever the realist, told Devin, “No, you won’t. They will attack you in the morning and they will come booming – skirmishers three deep. You will have to fight like the devil to hold your own until supports arrive.”

As the meeting ended, Buford told his subordinates, “The enemy knows the importance of this position and will strain every nerve to secure it, and if we are able to hold it, we will do well.” His signal officer, A. Brainerd Jerome, noted that Buford “seemed anxious, more so than I ever saw him.” Buford had every reason to believe his veteran troops could hold off the approaching Confederates for a time, but the critical question was for how long.

Later that night, Union pickets reported seeing Confederate campfires about a mile west of Herr Ridge, and Confederates in force north of Mummasburg Road, indicating a heavy concentration to the northwest. Buford sent a dispatch to General Pleasonton at 10:40 pm:

A. P. Hill’s corps, composed of Anderson, Heth, and Pender, is massed back of Cashtown, nine miles from this place. His pickets, composed of infantry and artillery, are in sight of mine… Rumor says Ewell is coming over the mountains from Carlisle.

Brigadier General John Buford had his one brief moment of glory on the first day of July 1863. Knowing that Lee’s infantry would be coming, Buford decided to resist the enemy as long as he could until the Union infantry arrived. He was the first to make contact with Lee’s army, and became the first hero of the battle.

Early that morning, Confederates of CSA General Henry Heth’s division of General A.P. Hill’s III Corps marched toward Gettysburg and encountered Buford’s pickets on the Chambersburg Pike, and General Buford skillfully arranged his men into a line where they could delay the Confederates’ advance.

As Heth’s infantry continued marching toward Gettysburg, a single shot rang out. Lt. Marcellus E. Jones of the 8th Illinois Cavalry had fired a shot “an officer on a white or light gray horse.” The Battle of Gettysburg had begun. Part of the reason Buford was able to hold their position at Gettysburg is because his dismounted cavalry used those breech-loading Spencer carbine rifles. His cavalry had fewer men firing, but their guns could be loaded and fired faster than other guns, so they were much more effective.

Buford’s cavalry also used dragoon tactics – three-quarters of his troopers were deployed in a heavy skirmish line while the remaining quarter held their horses – dismounted cavalry could fire more accurately. They remounted to move around the battlefield when necessary, and used the threat of a massed cavalry charge to slow the advance of the Confederate infantrymen to a crawl.

At about 9:30 AM, General John Reynolds rode up, and he and Buford talked briefly about deploying the Union infantry. Reynolds decided that McPherson’s Ridge was the best place to establish an artillery and infantry battle line. General Reynolds rode off to hurry his men forward, while Buford’s troopers fought for time.

Just when it appeared Buford’s cavalry line was going to collapse, Reynolds’ column of I Corps infantry appeared, and the battle was underway in earnest. Buford’s men dropped off to their flanks to provide protection, while at the same time continuing to provide timely intelligence on the arrival of new Confederate units.

General Buford withdrew his exhausted cavalrymen from the battle lines; they had checked Hill’s Corps for four hours. Their July 1 stand had been marked by chaos and blood. One soldier would describe the scene as “drivers yelling, shells bursting, shots shrieking overhead, smoke, dust, splinters – and carnage indescribable.”

When the Federal infantry were driven back in the late afternoon, Buford helped deter a Confederate advance by taking a menacing position on the Union left, near the Emmitsburg Road. The Union Army dug in their heels on Cemetery Hill, and from there, they delivered a decisive defeat to Lee’s battle-hardened troops over the next two days, and made Gettysburg the decisive battle of the American Civil War.

Morning Riders

Morning Riders

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

July 1, 1863, 5:15 a.m.

Mort Kunstler describes the painting:

“We see Buford riding his black horse followed by his headquarters flag. Closer to the viewer is the bugler in the yellow striped jacket, followed by the rest of Buford’s staff, coming out of the mist. The sun comes up over Culp’s Hill and hits the cupola [on the Lutheran Seminary in the background] first, and this was my chance for an unusual lighting effect. Buford left headquarters early with his entourage and headed northwest to supervise the line he had set up the night before on McPherson’s Ridge.”

Buford’s division had suffered more than 130 casualties on July 1 at Gettysburg. The men had fought for more than twelve hours, and had given the Confederate infantry as well as they had received. As Buford himself wrote, “The zeal, bravery, and good behavior of the officers and men on the night of June 30, and during July 1, was commendable in the extreme. A heavy task was before us; we were equal to it, and shall all remember with pride that at Gettysburg we did our country much service.”

By delaying the Confederate approach, Buford and his weary men had allowed the high ground and interior lines of defense to be held by the Army of the Potomac. Had Buford’s men not succeeded, had East Cemetery Hill fallen to the Confederates, the course of the battle might have taken a different turn.

Late that night, Buford’s division was ordered by General George Meade to watch the left flank of the army by guarding the hill known as Little Round Top. Buford deployed along the east side of Emmitsburg Road, approximately one-half mile from Little Round Top. Given the fighting two of his three brigades had engaged in the day before, this assignment was to allow them an opportunity to rest, while still providing an important service to the army.

The next morning, July 2, Buford’s men were the only cavalry on the field, patrolling a broad area around the Peach Orchard, performing the valuable duty of guarding the army’s left flank and reporting enemy movement. General Pleasonton, however, withdrew Buford’s entire force to Emmitsburg, Maryland, to resupply and refit in the army’s rear. They would never re-enter the battle.

The Aftermath

In the retreat from Gettysburg, Buford pursued the Confederates to Warrenton, Virginia, and was distressed that thousands of potential Confederate prisoners escaped on pontoons across the Potomac River, but he was proud of his men. Buford was always forthcoming with praise for his men, and made sure his views were communicated up the chain of command. Whenever able, he attended to Confederate wounded as readily as he attended to his own.

There was a palpable sense of frustration on Buford’s part with the Federal cavalry itself. Like more than a few officers, Buford had little tolerance for the political maneuvering throughout the Army of the Potomac. Whatever his frustrations with the Army and despite his successes, one thing became increasingly clear starting in the summer of Gettysburg and up until his death – John Buford was growing tired; in fact more than tired.

The end result was the beginning of a fatigue that would not ever cure itself, as Buford could never quite give himself over to even a decent night’s sleep. His poor sleeping habits were more like naps, simply wrapping a blanket about himself and sleeping on the ground near the campfire for a few hours. But there was more than this.

The general’s wife, Pattie Buford, was about to encounter the first of many hard losses in late July 1863. She had gone to visit her father in July only to arrive in time for his death. Pattie might have expected her ill father to die, but she would have hardly anticipated the death of their five-year-old daughter (Little Pattie), most likely to a disease contracted on their journey.

John was given a ten day leave; and as soon as he was able, he went directly home, fully aware of how harsh a blow this was to Pattie. He did not love his young daughter any less than his wife did, but because of his long absences, he had not formed a strong bond with his children. His direct concern was Pattie, who was reeling from the loss of her father and her only daughter within such a short span of time.

General John Buford Statue

General John Buford Statue

James E. Kelly, Artist

Gettysburg National Military Park

This bronze statue depicts General John Buford looking to the west, holding a pair of field glasses, wearing cavalry boots, with a sheathed sword at his side, just as he was on July 1, 1863. On July 1, 1895, at the dedication of the statue, General James H. Wilson paid tribute to his memory.

Buford reached Georgetown, Kentucky, on the evening of August 11, 1863, to find his wife broken-hearted. John’s devotion to his duty and to his wife were probably rarely manifested in words, but abundantly so in his deeds. He might have been a no-nonsense sort of person with a serious turn of mind, but he wasn’t devoid of caring deeply about those he loved.

Buford returned to the front and engaged in heavy fighting in Virginia, but he had distinguished himself at a heavy cost. In August, Buford took ill. His friend, General John Gibbon noted that Buford was having physical problems even during the Gettysburg Campaign. “He suffered terribly from rheumatism, and for days together could not mount a horse without help, but once mounted would remain in the saddle all day.” At 37, Buford was badly used up, but was too dedicated and too conscientious to leave the fight. By electing to stay, he was in effect, signing his own death warrant.

He was later engaged in many operations in central Virginia, rendering a particularly valuable service in covering General Meade’s retrograde movement in the Bristoe Campaign in October 1863. He was in an endless number of small engagements.

Buford became very tired during the Rappahannock Campaign and by the beginning of November, 1863, was having difficulty moving about his field headquarters. But within days, Buford was placing pickets and reviewing scouting reports, instead of convalescing on a sick leave granted by War Secretary Edwin Stanton. In a few days, however, refusing sick leave would be beyond John Buford’s control. Just before the beginning of the Mine Run Campaign, he was struck down by typhoid fever, and had to relinquish his command on November 21, 1863.

Buford was transferred to Washington, DC, but Pattie was visiting family in Illinois, and at first Buford did not have a place to stay. His former cavalry commander, George Stoneman, opened his home on Pennsylvania Avenue to Buford. For a brief time, it appeared that Buford was recovering while under the care of Stoneman and an army surgeon, and he happily received members of his command for short visits.

But by mid-December, it was obvious that Buford was dying. The strain of previous campaigns had lowered his resistance to infection, and his health began to fail rapidly. His temperature reached 104 degrees; dysentery and other complications further weakened his body. Pattie left Illinois for Washington.

General Stoneman requested that Buford be promoted to major general, and President Abraham Lincoln agreed, writing as follows: “I am informed that General Buford will not survive the day. It suggests itself to me that he will be made Major General for distinguished and meritorious service at the Battle of Gettysburg.” Informed of the promotion, Buford asked, “Does he mean it?” When assured the promotion was genuine, he said, “It is too late, now I wish I could live.”

His commission as major general of volunteers was presented to him on his deathbed. One of his aides signed Buford’s name on the form to accept the commission. Another aide served as a witness.

The rest of December 16, Buford floated back and forth between consciousness and a delirious state. At one time, he became upset with his teary-eyed free black servant, Edward, for a minor mistake, but later apologized. In his last hours, Buford was attended by his aide, Captain Myles Keogh and General Stoneman and Edward. Pattie was on the way, but would not arrive in time.

General John Buford died at 2:00 pm on December 16, 1863, of typhoid fever, exposure, and exhaustion, only five months after Gettysburg. He was thirty-seven years old. Myles Keogh held him in his arms as he died. His final reported words were: “Put guards on all the roads, and don’t let the men run to the rear.”

On the cold Sunday afternoon of December 20, 1863, a funeral procession came to a halt at the Presbyterian Church at Thirteenth and H Streets in Washington, DC, where memorial services were held. General Stoneman commanded the escort that included Grey Eagle, the old white horse Buford had ridden at Gettysburg.

The pallbearers included Generals Casey, Heintzelman, Sickles, Schofield, Hancock, Doubleday, and Warren. President Abraham Lincoln, Chief of Staff Henry Halleck, and Secretary of War Stanton were among the mourners. Pattie Buford was unable to attend due to illness.

After the service, Captains Myles Keogh and Wadsworth escorted Buford’s body to West Point for a military burial. Captain Keogh would survive the Civil War, only to perish at Custer’s Last Stand.

In 1865, twenty-five foot obelisk style monument was erected over Buford’s grave financed by members of his old division. The officers of his staff published a resolution that set forth the esteem in which he was held by his command:

… we, the staff officers of the late Major General John Buford, fully appreciating his merits as a gentleman, soldier, commander, and patriot, conceive his death to be an irreparable loss to the cavalry arm of the service. That we have been deprived of a friend and leader whose sole ambition was our success, and whose chief pleasure was in administering to the welfare, safety and happiness of the officers and men of his command… we are called to mourn the loss of one who was ever to us as the kindest and tenderest father, and that our fondest desire and wish will ever be to perpetuate his memory and emulate his greatness.

John Buford was a remarkable cavalry officer. His battlefield tactics were fairly traditional, but it was not in pitched battles that Buford excelled. He transformed his horse soldiers into a mobile, versatile force that could fight confidently alongside its infantry and artillery comrades. His accurate and timely reports of enemy movements – coupled with his tenacious defense of strategic ground – helped decide the outcome at Gettysburg.

In many ways, John Buford was a victim of his own self-effacing personality and his intense dislike of newspaper reporters, which prevented him from receiving the public recognition he deserved. An unnamed journalist described the grief and sadness felt by the soldiers in Buford’s division: “The men on picket mutter mournful ejaculations as they pass up and down their lonely walks by the red glare of the crackling campfire.”

Pattie Buford not only endured the loss of her husband, which occurred just a few months after the deaths of her father and her only daughter, but also the death of her only son James (still in his teens) in 1873, leaving her alone without husband or children. Since John’s death, she had collected his pension of $1 a month.

Martha (Pattie) McDowell Duke Buford died in 1903, at the age of 73, having survived her husband by forty years.

SOURCES

John Buford

Gettysburg Daily

The Man Himself

Beyond the Battle

General John Buford

Gettysburg July 1, 1863

Wikipedia: John Buford

Buford Arrives at Gettysburg

Portrait of General John Buford

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Union Cavalry Corps, First Division

Interesting Kin Folks In The Civil War

General John Buford, by Edward Longacre

General John Buford’s Spencer Carbine Rifles