Wife of Confederate General Richard Ewell

Lizinka Campbell was the daughter of a Tennessee State senator, who was also Minister to Russia under President James Monroe. She was born in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1820, and was named for the Russian Czarina who had become her mother’s close friend. She grew up to be a beautiful young lady.

Lizinka Campbell was the daughter of a Tennessee State senator, who was also Minister to Russia under President James Monroe. She was born in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1820, and was named for the Russian Czarina who had become her mother’s close friend. She grew up to be a beautiful young lady.

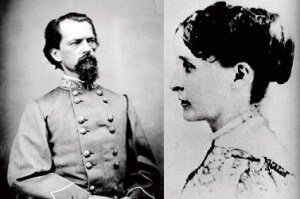

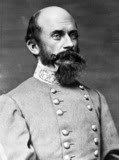

Image: General Richard Ewell

Somewhere along the way, Lizinka’s first cousin, Richard Stoddert Ewell, developed a great love for her. He was born in the District of Columbia and raised in Virginia. Though he sought Lizinka’s hand, she married another man.

On April 25, 1839, Lizinka married James Percy Brown, a lawyer who owned plantations in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama. When he and Lizinka became engaged, he was an attache in the American Embassy in Paris. Through his career and family connections, he moved in the highest circles of American and French society. Lizinka’s life was much like the one that she had known when her father had been a diplomat. She gave birth to two children.

From the time of Lizinka’s wedding to Brown, Richard remained a bachelor. He idealized Lizinka and set her up as a standard. For him, no other woman could match his romanticized picture of her.

One who knew him wrote:

He loved her when she was a young girl and being unsuccessful in his devotions, remained a soldier and bachelor on the frontier for many years, since he did not hope to find her equal in all the noble qualities of person, head and heart, which were required by his exacting ideal…

So, Ewell spent much time in the deserts of Arizona and New Mexico, where he fought Apaches, escorted traders through dangerous territory and served in the Mexican War. He led a hard existence when compared to the refined lives of his distinguished relatives. His life was even further from the glamour and luxury to which the Browns were accustomed.

Lizinka’s husband died in 1844. Her children were still very young, and she decided to move into her father’s home in Nashville. When her father died, she inherited much of his great wealth. She proved to be as shrewd as she was beautiful, for she managed the assets she had inherited so well that her fortune increased even more.

When the Civil War broke out, Richard Ewell joined the Confederate Army and became a member of General Robert E. Lee‘s staff. Lizinka’s son, Campbell Brown, was Richard’s aide. With her son so near to him, Richard naturally thought of Lizinka. He was anxious for her safety, as she was still living in Nashville.

Lizinka outfitted a Rebel company formed in Maury County by some of her cousins. The group was known as the Brown Guards. Richard had good reason to fear that Lizinka’s loyalty to the Confederacy might cause trouble for her. When Union forces occupied Nashville in 1862, Lizinka fled to Virginia, and Military Governor Andrew Johnson lived in her house in Nashville.

Richard Ewell’s right knee had been shattered in battle, and his leg had to be amputated. Lizinka nursed him back to health and he finally persuaded her to marry him. By this time, he was forty-six years old, and the beating his skin and body had taken during his years as a soldier made him look even older. He became a devoted husband, but seemed unaware that their marriage had changed her name, and always proudly introduced her as My wife, Mrs. Brown.

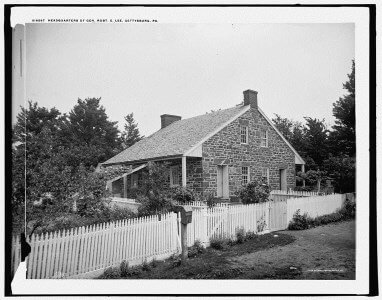

After their wedding in Richmond on May 26, 1863, Lizinka managed General Ewell’s affairs, even down to overseeing the couriers who carried his dispatches. General Robert E. Lee’s soldiers deeply resented her attempts to manage Ewell’s military affairs, and many officers unfairly blamed her for Ewell’s poor generalship and repeated battlefield failures.

In nineteenth-century America, men believed that marriage should subordinate women to male authority, but occasionally the roles were reversed, and a husband found himself under a strong-minded wife. Evidence shows that the relationship between Lizinka Campbell Brown and General Richard Ewell was like that, largely because she had succeeded outside her appointed sphere as a single woman, ranking as one of Tennessee’s wealthiest planters.

Some even charged that officers who married during the war suddenly lost their courage in battle and their efficiency in camp. The perception that Richard was henpecked made him a popular topic of army gossip. The idle chatter tended to alienate the couple from acceptable social circles. It is also possible that it upset the chemistry of their relationship.

After his long recovery, Ewell returned to the Army of Northern Virginia for the Battle ofChancellorsville. When General Stonewall Jackson was mortally wounded on May 3, 1863, he suggested that Ewell replace him. On May 23, Ewell was promoted to lieutenant general and commander of the Second Corps.

His corps took the lead in the invasion of Pennsylvania in June 1863, and almost reached the state capital of Harrisburg before being recalled by Lee to concentrate at Gettysburg. These successes led to favorable comparisons with Jackson.

But at the Battle of Gettysburg, Ewell’s military reputation started a long decline. On July 1, 1863, Ewell’s corps approached Gettysburg from the north and smashed the Union XI Corps and part of the I Corps, driving them back through the town and forcing them to take up defensive positions on Cemetery Hill south of town.

General Lee had just arrived on the field and saw the importance of this position. He sent orders to Ewell that Cemetery Hill be taken “if practicable,” but Ewell chose not to attempt the assault. Lee’s order has been criticized because it left too much discretion to Ewell. However, he never shirked responsibility for his decisions at Gettysburg, but the loss of a leg may have led him to be too cautious.

Ewell’s luck continued to be bad, and he was wounded at Kelly’s Ford, Virginia, in November. He was injured again in January 1864, when his horse fell over in the snow.

In May 1864, Ewell led his corps in the Battle of the Wilderness and performed well, enjoying the rare circumstance of a slight numerical superiority over the Union corps that attacked him. But a few days later, in the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, his horse was shot out from under him, and he took a bad fall.

Ewell began hysterically berating some of his soldiers, who were retreating in the face of superior Union firepower. He beat them over the back with the flat of his sword, trying to get them to turn around and fight.

General Lee reasoned that Ewell’s lingering injuries were the cause of his problems, and relieved Ewell of corps command. Lee reassigned Ewell to command the garrison of the Department of Richmond, which was by no means an insignificant assignment, given the extreme pressure Union forces were applying to the Confederate capital.

In September 1864, Ewell managed to save Richmond from capture by some 8000 Federals with only a handful of Southern troops. Gathering about 200 stragglers, Ewell and his ragtag crew stood, without entrenchments, silhouetted against an empty woods to their rear. Union troops, thinking reinforcements were in the woods, refused to attack.

In April 1865, during the retreat toward Appomattox Court House, Ewell commanded a mixed corps of soldiers, sailors and marines. They were surrounded and forced to surrender at Sayler’s Creek, a few days before Lee’s surrender. Ewell was held as a prisoner of war at Fort Warren in Boston Harbor until July 1865.

While imprisoned, Ewell organized a group of sixteen former generals at Fort Warren, including Edward “Allegheny” Johnson and Joseph Kershaw, and sent a letter to General Ulysses S. Grant about the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, for which they said no Southern man could feel anything other than ‘unqualified abhorrence and indignation,’ and insisting that the crime should not be connected to the South.

After the war, Lizinka and Richard moved to a farm that she had inherited in Spring Hill, Tennessee. They shared an interest in progressive farming, and Richard was elected president of the Maury County Agricultural Society and president of the Board of Trustees of the Columbia Institute. He doted on Lizinka’s children and grandchildren.

In January 1872, the General fell ill from a severe chill. The doctors labeled the disease typhoid-pneumonia. Again Lizinka committed herself to nursing Richard back to health, but within a few days, she took sick.

Lizinka Campbell Brown Ewell died on January 20, 1872. The family was afraid to tell Richard that his wife was dead – they feared that in his weakened state, his grief might kill him. No one told him of her death until the day of her burial.

Richard Stoddert Ewell died of pneumonia on January 25, 1872, just five days after Lizinka succumbed to the same illness. He left instructions that he wanted nothing disrespectful to the United States inscribed on his headstone.

Richard and Lizinka Ewell were both buried in the Old City Cemetery in Nashville. An inscription in the window of the church they attended reads, “R.S.E., 1818-1872, L.C.E., 1820-1872 – In their deaths they were not divided.”

Historian Douglas S. Freeman described Ewell as:

Bold, pop-eyed and long beaked, with a piping voice that seems to fit his appearance as a strange, unlovely bird; his sharp tongue matched his fighting spirit, but the loss of his leg, headaches, indigestion and sleeplessness drained both his energy and effectiveness.

All this may be true, but he did not quit.

SOURCES

Richard S. Ewell

He Always Loved Her

General Richard Ewell’s Failure on the Heights

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Lieutenant General Richard Stoddert Ewell