She Dedicated Her Life to Women’s Rights

Susan Brownell Anthony was a feminist and reformer whose Quaker family was committed to social equality. She began collecting anti-slavery petitions when she was 17 and became an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society at age 36. In 1869, Anthony, alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton, founded the National Woman Suffrage Association, and they played a pivotal role in the women’s suffrage movement.

Early Years

Susan B. Anthony was born February 15, 1820 in Adams, Massachusetts to Quaker Daniel Anthony and Lucy Read Anthony, who shared a passion for social reform. Daniel encouraged all of his children, girls as well as boys, to be self-supporting; he taught them business principles and gave them responsibilities at an early age.

When she was seventeen, Anthony attended a Quaker boarding school in Philadelphia, but her family was financially ruined in the Panic of 1837. Susan had to return home after only one term. They were forced to sell everything they owned at an auction, but a maternal uncle bought their belongings and restored them to the family.

In 1846, at age 26, Anthony accepted a position as head of the girls’ department at Canajoharie Academy. She taught there for two years and earned $110 a year.

Education Reform

In her speech at the state teachers’ convention of 1853, Anthony called for women to be admitted to the professions and for better pay for women teachers. In 1859 Anthony spoke before state teachers’ conventions in Troy, New York and Massachusetts for coeducation (boys and girls educated together), arguing there were no differences between the minds of males and females.

Anthony fought for equal educational opportunities for all regardless of race, calling for all schools, colleges, and universities to open their doors to women and former slaves. She also campaigned for the right of black children to attend public schools.

In the 1890s Anthony served on the board of trustees of Rochester’s State Industrial School and campaigned for coeducation and equal opportunity for boys and girls. She raised $50,000 in pledges to ensure the admittance of women to the University of Rochester. Fearing she might miss the deadline, she put up the cash value of her life insurance policy. The University was forced to make good its promise and women were admitted for the first time in 1900.

Anti-Slavery Work

In 1845, the family purchased a farm on the outskirts of Rochester, New York, partly paid for with Lucy’s inheritance. The Anthony farmhouse soon became the Sunday afternoon gathering place for local activists, including prominent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and former slave Frederick Douglass, who became Anthony’s lifelong friend.

Susan B. Anthony played a key role in organizing an anti-slavery convention in Rochester in 1851. She was also a stationmaster on the Underground Railroad, and her diary entry in 1861 stated: “Fitted out a fugitive slave for Canada with the help of Harriet Tubman.”

In 1856 Anthony became an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society, putting up posters, arranging meetings, distributing pamphlets, and making speeches. Hostile mobs and flying missiles thrown in her direction did not deter her. In Syracuse her image was dragged through the streets, and she was hung in effigy.

Women’s National Loyal League

In 1863, during the Civil War, Anthony and others organized the Women’s National Loyal League – the first national women’s political organization in the United States. In support of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which would abolish slavery, the League conducted the largest petition drive in American history – nearly 400,000 signatures. Anthony worked to organize the operation of recruiting and coordinating some 2000 volunteer petition collectors.

The League also provided a platform for women’s rights by telling the public that petitioning was the only political tool available to women. With a membership of 5000, this organization developed a new generation of women leaders and provided experience and recognition for newcomers like Anna Dickinson. The League demonstrated the value of a women’s movement that had been only loosely organized up to that point, and a widespread network of women activists expanded the pool of talent that was available to reform movements after the war.

These women’s rights activists supported equal rights for women and people of any race, including the right to vote. They campaigned for the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” including former slaves recently freed.

They also worked tirelessly for the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibits the federal and state governments from denying a citizen the right to vote based on their “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” They were bitterly disappointed when women were excluded from those amendments.

Women’s Rights Activist

In 1851, at Seneca Falls, New York, Amelia Bloomer introduced Susan B. Anthony to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who wrote this about their first meeting:

Walking home with the speakers, who were my guests, we met Mrs. Bloomer with Miss Anthony on the corner of the street waiting to greet us. There she stood with her good, earnest face and genial smile, dressed in gray delaine, hat and all the same color relieved with pale-blue ribbons, the perfection of neatness and sobriety. I liked her thoroughly from the beginning.

Anthony and Stanton became lifelong friends and partners in social reform movements, particularly women’s rights. Their relationship led Anthony to join the women’s rights movement in 1852, and she attended her first women’s rights convention in Syracuse that same year. At that time Stanton was housebound raising seven children, and Anthony often supervised the children, giving Stanton time to write.

There were hardships in the early days. The women’s movement rarely had enough money to execute its programs. And, at that time, few women had an independent source of income; those with jobs were required by law to give their wages to their husbands. There were no precedents, so they created them as they went.

In 1853, Anthony organized a convention in Rochester to launch a state campaign for improved property rights for married women. In February 1856 Anthony traveled to Albany and presented petitions to the Legislature, requesting that a new law be passed to allow women to control her wages and have custody of her children. She was referred to Samuel Foote, head of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Mr. Foote’s incredible response:

The committee is composed of married and single gentlemen. The bachelors … have left the subject pretty much to the married gentlemen. … the ladies always have the best place and choicest titbit at the table. They have the best seat in the cars, carriages and sleighs; the warmest place in winter and the coolest in summer. They have their choice on which side of the bed they will lie, front or back. …

It has thus appeared to the married gentlemen of your committee, being a majority … that if there is any inequality or oppression in the case, the gentlemen are the sufferers. They, however, have presented no petitions for redress, having doubtless made up their minds to yield to an inevitable destiny.

On the whole, the committee have concluded to recommend no measure, except that they have observed several instances in which husband and wife have both signed the same petition. In such case, they would recommend the parties to apply for a law authorizing them to change dresses, so that the husband may wear petticoats, and the wife breeches, and thus indicate to their neighbors and the public the true relation in which they stand to each other.

In 1860, after years of advocacy by Anthony and otheres, the Legislature passed the New York State Married Women’s Property Bill, which allowed married women to own property, keep their wages, and have custody of their children. Anthony and Stanton then campaigned for more liberal divorce laws in New York.

The Revolution

Anthony and Stanton published a weekly women’s rights newspaper called The Revolution in New York City from January 8, 1868 and February 17, 1872. Its combative style matched its name, and it focused on women’s rights, especially women’s suffrage. Anthony managed the business side while Stanton served as the editor.

After more than two years of mounting debts, Anthony transferred The Revolution to Laura Curtis Bullard, a wealthy women’s rights activist who published the paper two more years. Despite its short lifespan, the paper helped move women’s issues back into the national spotlight after the Civil War and established Stanton and Anthony as public figures whose demands for equal rights were not ignored.

Working Women’s Advocate

While publishing The Revolution in New York Anthony came into contact with women in the printing trades. In her newspaper, she advocated an eight-hour workday for women, equal pay for equal work, the purchase of American-made goods, and encouraged working women to form women’s labor organizations.

In 1870 Anthony founded the Working Women’s Association (WWA), which reported on working conditions and provided educational opportunities for its workers. The WWA concentrated in the printing industry in its early days; its members included women who were employed, or self-employed, in print shops.

The Association’s membership grew to include more than a hundred working women, in addition to journalists and other women whose work was more mental than manual. When printers went on strike in New York, she urged companies to hire women. She believed this was an opportunity to show that they could do the job as well as men and therefore deserved equal pay.

Susan B. Anthony also advocated dress reform for women. She cut her hair and wore the Bloomer costume for a year before she realized that this radical dress was detracting from the other causes she supported.

Suffragist

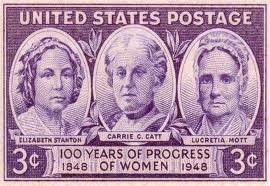

In 1866, Anthony and Stanton initiated the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) campaigned for equal rights for both women and African Americans. The leadership of this new organization included such prominent activists as Lucretia Mott and Lucy Stone. Some abolitionist leaders wanted women to postpone their campaign for suffrage until after African American males were given the right to vote.

The AERA eventually divided into two wings. One group was willing for black men to achieve suffrage first. The wing led by Anthony and Stanton insisted that women and black men should be enfranchised at the same time; they wanted to work toward an independent women’s movement that would no longer be dependent on abolitionists. The AERA effectively dissolved in May 1869, leaving two competing women’s suffrage organizations in its aftermath.

Susan B. Anthony was convinced by her work in social reform movements that women needed the vote if they were to influence public affairs. In 1869, after the demise of the AERA, Anthony and Stanton founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and began to campaign for a constitutional amendment giving women the right to vote.

The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) adopted a strategy of getting the vote for women state-by-state; some territories or new states in the West were the first to extend suffrage to women. The territory of Wyoming was the first to give women the vote in 1869, long before it became a state (1890). Anthony campaigned for women’s suffrage in the West during the 1870s.

Anthony, three of her sisters, and a few other women in Rochester voted in the 1872 Presidential Election. On November 18, 1872, a U.S. Deputy Marshal arrested Anthony for illegally voting. She was arraigned in Rochester Common Council chambers along with the other women voters and the election officials who had allowed her to vote .

Susan B. Anthony was tried and convicted in a highly publicized trial, which gave her the opportunity to spread her arguments to a wider audience. The judge fined her $100, and although she refused to pay it, the authorities declined to take further action.

Anthony traveled extensively and gave as many as 75 to 100 speeches per year in support of women’s suffrage. She worked on many state campaigns. By 1877, she had gathered petitions from 26 states with 10,000 signatures, and she presented them to Congress.

Susan B. Anthony Amendment

In 1878, Anthony and Stanton arranged for Senator A.A. Sargent of California to present to Congress an amendment to the U.S. Constitution giving women the right to vote. The women proposed a revision of the Sixteenth Amendment that would read:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

What was popularly called the Susan B. Anthony Amendment became the main lobbying strategy for suffragists committed to winning the vote through a constitutional amendment. Though Congress repeatedly rejected the revision, Sargent continued to propose it. In the years between 1878 and 1906, Anthony appeared at every Congressional session to ask for passage of a suffrage amendment.

Between 1881 and 1885 Anthony, Stanton, and suffragist Matilda Joslyn Gage collaborated on the multi-volume book, History of Woman Suffrage. Anthony and Ida Husted Harper edited the final volume, which was published in 1902.

In 1887 the new National American Woman Suffrage Association was created with Stanton as president and Anthony as vice-president. Anthony became president in 1892 when Stanton retired.

Anthony campaigned in the West in the 1890s to make sure that the territories that had granted women the vote were not blocked from admission to the Union. She also helped to establish the World’s Congress of Representative Women at the World’s Fair held in Chicago in 1893.

Public perception of Susan B. Anthony changed radically during her lifetime. When she began campaigning for women’s rights in the 1850s, she was harshly ridiculed. By 1900, she had established her worth as an activist and champion for women. That year President William McKinley invited her to celebrate her eightieth birthday at the White House that year.

Anthony never married, and she remained active until her death.

I don’t want to die as long as I can work; the minute I can not, I want to go.

~ Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony died March 13, 1906 at her home in Rochester.

The Susan B. Anthony Silver Dollar was minted from 1979 to 1981; it brought a new awareness of her life in activism to the public.

SOURCES

Susan B. Anthony House

Wikipedia: The Revolution (Newspaper)

Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony in Two Volumes