One of the First Feminists in the United States

Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826-1898) is the forgotten mother of the women’s rights movement. She was a contemporary of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, with whom she co-authored the first three volumes of The History of Woman Suffrage. Gage was always one of the more radical leaders of the movement and her writing focused on the significant accomplishments of women in invention, military affairs and in history.

Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826-1898) is the forgotten mother of the women’s rights movement. She was a contemporary of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, with whom she co-authored the first three volumes of The History of Woman Suffrage. Gage was always one of the more radical leaders of the movement and her writing focused on the significant accomplishments of women in invention, military affairs and in history.

Early Years

Matilda Joslyn Gage was born on March 24, 1826 in Cicero, New York. An only child, she was raised in a household dedicated to antislavery. Her father Dr. Hezekiah Joslyn was a nationally known abolitionist, and the Joslyn home was a station on the Underground Railroad.

Matilda Joslyn received an advanced education from her father and completed her formal schooling at the Clinton Liberal Institute in Clinton, New York. She later wrote:

I am indebted to my father for something better than a collegiate education. He taught me to think for myself, and not to accept the word of any man, or society, or human being, but to fully examine for myself. My father was a physician, training me himself, giving me lessons in physiology and anatomy, and while I was a young girl he spoke of my entering Geneva Medical College, whose president was his old professor… but that was not to be. I had been married quite a number of years when Elizabeth Blackwell was graduated from that institution [1849]…

In January 1845 Matilda Joslyn married merchant Henry Hill Gage, with whom she would have four children: Helen Leslie (1845), Thomas Clarkson (1848), Julia Louise (1851) and Maud (1861). Matilda and her husband lived for a short time in Syracuse and Manlius, before permanently settling in Fayetteville in 1854, where she lived for the rest of her life. Gage’s entire life was spent within a thirty mile radius of Syracuse, New York.

As a young wife and mother in 1850, Gage signed a petition stating that she would face the penalty of a six month prison term and a $2,000 fine rather than obey the newly enacted Fugitive Slave law, which made criminals of anyone assisting slaves to freedom anywhere in the United States.

One of the proudest acts of my life; one that I look back upon with most satisfaction is that when Rev. Mr. Loguen [Syracuse conductor of the Underground Railroad] …went to the village of my residence to ascertain the names of those upon whom runaway slaves might depend for aid and comfort on the way to Canada, I was one of the two solitary persons… who dared thus publicly defy ‘the law’ of the land, and for humanity’s sake rendered ourselves liable to fine and imprisonment… for the crime of feeding the hungry, giving shelter to the oppressed and helping the black slaves on to freedom.

Career in Social Reform

Although occupied with both family and antislavery activities, Gage was drawn to a new cause: the women’s rights movement. Her life’s work would become the struggle for the complete liberation of women. Unable to attend the first Women’s Rights Convention held in Seneca Falls in 1848, Gage attended the third national convention in Syracuse in 1852, where she made her first public address.

While Gage’s background was much more varied than many young women of her day, even her early training did not make her transition to outspoken feminist an easy one. She was only 26 years old when she spoke at the Women’s Rights convention in 1852. She was inaudible to her audience and “trembling in every limb” at the end of her speech.

In 1862, Gage gave the flag presentation speech to the 122nd Regiment as they were leaving to fight in the Civil War. While President Abraham Lincoln stated the war was being fought to preserve the Union, Gage told the soldiers they were fighting for an end to slavery and to win freedom for all citizens. She predicted the failure of any course of defense of the Union that did not emancipate the slaves. Gage was an enthusiastic organizer of hospital supplies for Union soldiers during the war.

It was not until after the Civil War, when her children were older and her family responsibilities had lessened, that Matilda Joslyn Gage went into serious political and social activism. She believed that the rights of all people were intertwined. Just as she had fought slavery and spoke out for women’s rights, she also championed Indian rights.

Gage, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton went on to become the “triumvirate” of the woman’s rights movement and founders of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) (1869-1889). Gage served in various offices of that organization, and a contributor to its newspaper The Revolution. She also helped organize the Virginia and New York State Woman Suffrage Associations, and was an officer in the New York association for twenty years.

In November 1869 the women’s rights movement split into two factions over a fundamental disagreement. The New York-based National Woman Suffrage Association created by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton opposed the 15th Amendment unless it also gave women the right to vote. The Boston-based American Woman Suffrage Association created by Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell and Julia Ward Howe supported the 15th Amendment, believing that all men should get the right to vote first and then women.

The 15th Amendment, ratified on February 3, 1870, stated: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” It mentioned nothing about gender, so Gage was one of hundreds of women across the country who unsuccessfully tried to test the new law by attempting to vote in 1871.

When Susan B. Anthony successfully voted in the 1872 presidential election, she was arrested and put on trial. Gage alone among the NWSA women saw the importance of this political event and came to Anthony’s aid. Gage gave a speech entitled, “The United States on Trial, not Susan B. Anthony,” sat with Anthony throughout the proceedings and stood in support when Anthony was found guilty and refused to pay the imposed fine.

Never entirely comfortable on the speaker’s platform, Gage was a talented writer an effective advocate of equal rights for women with her pen. Her writings included the influential pamphlet Woman as Inventor (1870), Woman’s Rights Catechism (1871), Who Planned the Tennessee Campaign of 1862? and The Dangers of the Hour (1890).

During the 1870s Matilda Joslyn Gage wrote a series of articles speaking out against the brutal and unfair treatment of Native Americans. Gage was inspired by the government of the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy – Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca and Tuscarora – where “the power between the sexes was nearly equal.” This indigenous practice of women’s rights became her vision. She was adopted into the Wolf Clan of the Mohawk nation and given the name Ka-ron-ien-ha-wi (Sky Carrier).

Gage created a unique strategy in 1877 based on the way in which convicted male criminals who had lost the right to vote could directly petition Congress and regain their suffrage. Following the form they used, Gage petitioned Congress to grant her “relief from her political liabilities” and to restore her lawful right to vote as a citizen. A bill was introduced in Congress, and although it was defeated, the resulting publicity convinced the NWSA to adopt Gage’s plan as a major tactic in the suffrage struggle.

In 1880 Gage’s leadership of the New York Woman Suffrage Association gained for women the right to vote and run for office in school board elections in the school districts where they paid their taxes. Gage held meetings in her home to organize the women of Fayetteville to vote and led 102 Fayetteville women to the polls. They elected an all-female slate of officers, with Gage being the first to cast her ballot.

The test case of the law came thirteen years later, when Gage was slapped with a supreme writ by a marshal who knocked on her door one day in 1893. A recognized leader in the movement, Gage became the test case for the constitutionality of the New York law that gave women the franchise in school elections. Gage lost her case and that limited right was taken away from New York women.

In 1875 Gage, Stanton and Anthony had begun writing The History of Woman Suffrage. The first three volumes, covering the period from 1848 to 1883, took over 14 years to write and totaled more than 3,000 pages, much of the work being done in Gage’s Fayetteville home. “The three names,” predicted a women’s rights newspaper, “will ever hold a grateful place in the hearts of posterity.”

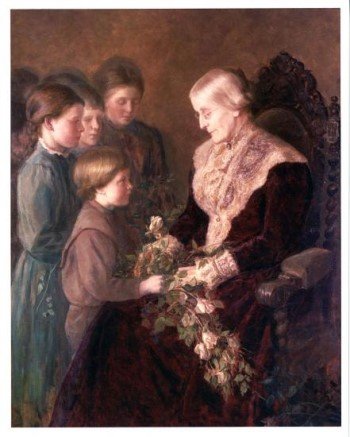

During this time Susan B. Anthony spent so much time in the Gage house that the family called the guest bedroom “The Susan B. Anthony Room.” Anthony wrote her name with a diamond in the upstairs library window on one of her visits; it is still there.

A prolific writer, Gage also served as a correspondent for newspapers from New York to California, primarily writing about woman’s rights issues and activities. Concerned that women were being written out of history, Gage documented many previously unacknowledged accomplishments of her sex.

Gage maintained that the cotton gin was not really invented by Eli Whitney, but rather by Catherine Littlefield Greene, who had the idea for the gin and hired Whitney to build it. Gage also argued that the detailed planning of the crucial Tennessee Campaign of 1862, an important military campaign that changed the course of the Civil War – generally credited to General Ulysses S. Grant – was actually the brainchild of Anna Ella Carroll.

All four of Gage’s children moved to the Dakota Territory during the 1880s, where Gage visited often. On November 9, 1882, Gage’s daughter Maud married L. Frank Baum – author of children’s books, best known for writing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Gage’s husband Henry Gage died on September 16, 1884 after a long illness.

Late Years

In October 1886 Gage joined the New York City Woman Suffrage Association’s protest at the unveiling of the Statue of Liberty and gave a speech. Suffragists called it the greatest hypocrisy of the 19th century that liberty was represented as a woman in a land where not a single woman had liberty.

Gage became discouraged with the slow pace of suffrage efforts in the 1880s and growing friction within the NWSA. When Susan B. Anthony led her followers in merging the two existing suffrage organizations, thereby bringing in the conservative Women’s Christian Temperance Union forces, Gage left the suffrage movement.

Gage then formed the Women’s National Liberal Union in 1890. The WNLU, made up of anarchists, prison reformers, labor leaders and feminists, was viewed as one of the most radical organizations in the country, and Gage’s mail was intercepted by the government.

The WNLU reflected in particular Gage’s belief that established churches were a major bulwark of male supremacist teaching, a view she expanded on in her book Woman, Church, and State (1893), in which she documented the misogyny committed in the name of the Christian religion, from trafficking in women to sexual abuse by the clergy. With her clear and unapologetic writing style, and her wealth of knowledge, she backed up her theories with facts drawn from over 2000 years of human history.

Gage decried the unequal treatment of the prostitute and her client and the “practice of non-conviction or of pardoning” in rape trials. Unequal pay, the double standard, wife battering, the sexual abuse of female children – she addressed all these issues and more. One of the few women who stood beside Gage when she took on her unpopular battle against the Church was Lillie Devereux Blake, one of the major figures in the NWSA.

Stanton chose to become president of Anthony’s combined National American Woman Suffrage Association rather than join Gage’s group. Anthony denounced Gage’s “secession” (as she called it) from the suffrage ranks, and Gage spent her last eight years estranged from most of her movement allies and friends of the previous forty years.

Matilda Joslyn Gage died in Chicago, Illinois, on March 18, 1898, while visiting at the home of her daughter Maud Gage Baum.

Susan B. Anthony was more famous and lived longer than the other two members of the suffrage triumvirate – Matilda Joslyn Gage and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Anthony’s biography, Stanton’s autobiography, later volumes of The History of Woman Suffrage and other secondary sources all combined to become the prevailing version of women’s history, quoted extensively by writers and historians during the years that followed.

Throughout her life and work, Gage did not call attention to herself – only to the issues of human rights to which she devoted her life. She did not keep a journal and never wrote her life story. Fortunately, her children and grandchildren saved an extensive collection of her clippings and correspondence. Through her letters, newspaper articles and other primary sources, historians have been able to reconstruct Gage’s important role in the woman’s rights movement and restore her to her proper place in history.

Gage spoke these words during the Civil War, and they characterize her lifelong commitment to the struggle of freedom for all people:

Until liberty is attained – the broadest, the deepest, the highest liberty for all – not one set alone, one clique alone, but for men and women, black and white, Irish, Germans, Americans and Negroes, there can be no permanent peace.

SOURCES

Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation

National Women’s History Project: Matilda Joslyn Gage