First part here: Black Women Writers of the 19th Century

Black Women Writers Through Civil War and Reconstruction

The nineteenth century was a formative period in African-American literary and cultural history. Law and practice forbade teaching blacks to read or write. Even after the American Civil War, many of the impediments to learning and literary productivity remained. Nevertheless, more African-Americans than we yet realize turned their observations, feelings, and creative impulses into poetry, short stories, histories, narratives, novels, and autobiographies.

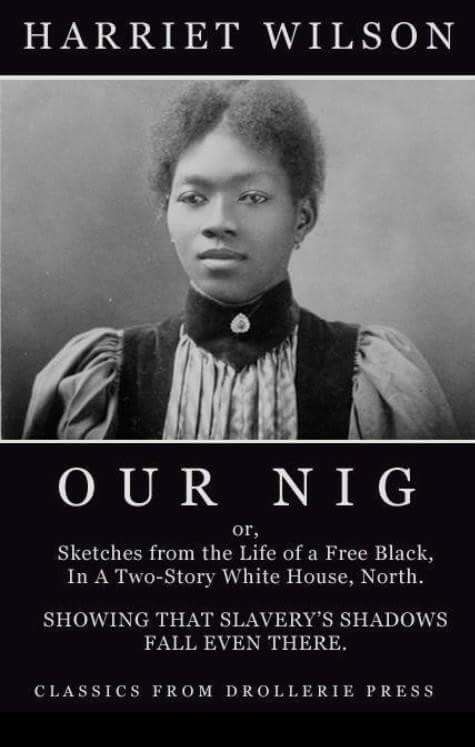

Harriet Wilson (1825-1900)

Considered the first female African-American novelist, Harriet Wilson has also been called the first African-American of either gender to publish a novel on the North American continent. Her novel Our Nig, or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black was published anonymously in 1859 in Boston, Massachusetts; it was not widely read. In 1982, scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. discovered the novel and documented it as the first African-American novel published in the United States.

Born a free person of color in New Hampshire, Harriet was the daughter of Irish washerwoman Margaret Ann Smith and Joshua Green, an African-American barrelmaker. She lost her parents while very young, and she supported herself by working as a servant until the age of eighteen. Struggling to make a living as an adult, Harriet married escaped slave Thomas Wilson October 6, 1851 in Milford, New Hampshire, but he abandoned her soon after they married. He had told Harriet that he had never been a slave and that he had created the story to gain support from abolitionists.

Pregnant and ill, Harriet was sent to the Poor Farm in Goffstown, where her son, George Mason Wilson, was born in June 1852. Thomas Wilson soon reappeared and took the two away from the Farm. He worked as a sailor at sea but died soon after. Harriet could not make enough money to support them both and provide for his care while she worked. She returned her son to the care of the Poor Farm, where he died at the age of seven on February 16, 1860.

Widow Harriet Wilson then moved to Boston, hoping for more employment opportunities. On September 29, 1870, Harriet married John Gallatin Robinson, an apothecary who was nearly 18 years younger than Wilson. While living in Boston, Harriet Wilson wrote Our Nig. On August 18, 1859, she copyrighted her work by depositing a copy of the novel in the Office of the Clerk of the U.S. District Court of Massachusetts. On September 5, 1859, the novel was published anonymously by George C. Rand and Avery, a publishing firm in Boston.

From 1867 to 1897, “Mrs. Hattie E. Wilson” was listed in the Boston Spiritualist newspaper, Banner of Light as a trance reader and lecturer. She was active in the local Spiritualist community, and she gave lectures wherever she was wanted. She spoke at camp meetings, in theaters, and in private homes throughout New England. She shared the podium with speakers like Victoria Woodhull, delivering lectures on labor reform and children’s education.

From 1879 to 1897, Wilson was the housekeeper of a boarding house in a two-story dwelling at 15 Village Street, where she rented out rooms, collected rents and provided basic maintenance. There is no evidence that she wrote anything else for publication except Our Nig. On June 28, 1900, Hattie E. Wilson died in the Quincy Hospital in Quincy, Massachusetts.

Scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr. rediscovered Our Nig in 1982 and documented it as the first novel by an African American to be published in the United States. His discovery and the novel gained national attention.

In 2006, history professors William L. Andrews and Mitch Kachun brought to light Julia C. Collins’ The Curse of Caste; or The Slave Bride (1865), first published in serial form in the Christian Recorder, the newspaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. They published The Curse of Caste in 2006 and maintained that it should be considered the first novel by an African-American published in the U.S. They argued that Our Nig was more autobiography than fiction.

Gates responded that numerous other novels and other works of fiction of the period were in some part based on real-life events and were in that sense autobiographical, but they were still considered novels. Examples include Fanny Fern‘s Ruth Hall (1854); Louisa May Alcott‘s Little Women (1868-1869); and Hannah Foster‘s The Coquette (1797).

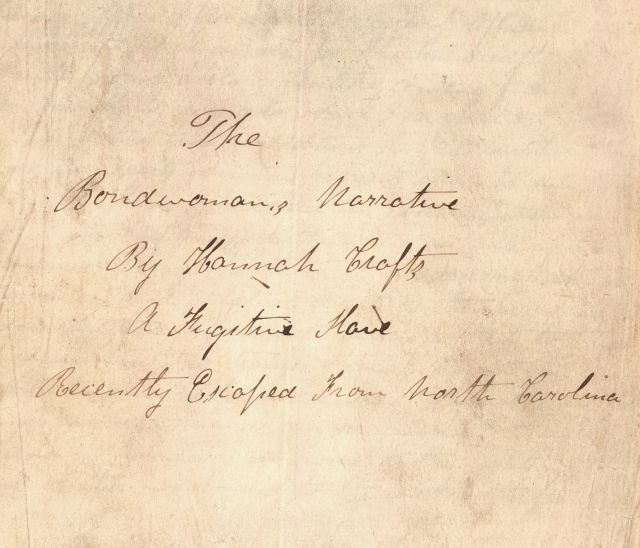

Hannah Crafts (1830s-1880s)

Hannah (Bond) Crafts was an African-American writer who escaped from slavery in North Carolina in 1857 and went to the North and settled in New Jersey. There she married Thomas Vincent and became a teacher. She wrote The Bondwoman’s Narrative, the only known slave narrative written by a female fugitive slave. Slave narratives are autobiographical works written by freed or escaped slaves.

Hannah Crafts was the property of John Hill Wheeler of Murfreesboro, North Carolina; she served Wheeler’s wife Ellen as a lady’s maid. Crafts escaped in 1857 from their North Carolina plantation in Lincoln County. Hannah ran away after she was dismissed from the house and told to work in the fields, which was back-breaking work. She settled in New Jersey, where she married a minister and became a Sunday school teacher.

A named Jane Johnson had escaped from Wheeler in July 1855 while she was traveling with Wheeler and his family in Philadelphia. Johnson was to care for his family while Wheeler was serving as the U.S. Minister to Nicaragua. Wheeler did not realize that slaves voluntarily brought by their masters to the free state of Pennsylvania were considered by law to be free. Johnson sent a message to the Vigilance Committee of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society whose purpose it was to advise slaves of their rights and help them gain freedom. The Society freed Johnson before she boarded the ship to Nicarauga.

Hannah Crafts wrote a novel, The Bondwoman’s Narrative by Hannah Crafts, Fugitive Slave from North Carolina. The manuscript was found years later in a New Jersey attic and was held privately for many years. In 2001 it was purchased at auction by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. – professor of African-American literature and history at Harvard University – who published in 2002. It quickly became a bestseller. Her identity was documented in 2013 by Gregg Hecimovich, validated many details of her life; his findings were supported by Gates and other scholars.

Quote from The Bondwoman’s Narrative:

For say what you will of lovers, there’s nothing so flattering to female vanity as the praise of a husband, because it is universally considered a more difficult matter to retain affection than to win it.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911)

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper wrote four novels, several volumes of poetry, and numerous stories, poems, essays and letters. Born to free parents in Baltimore, Maryland, Harper received an excellent education at a school run by her uncle, William Watkins. Orphaned while very young, Frances was raised by relatives. At the age of thirteen, she was sent out to earn a living.

Young Frances found work as a servant and babysitter for the Armstrongs, a white family in Baltimore. Mr. Armstrong owned a bookstore, and he allowed her free access to books and encouraged her to develop her love for writing. When she was in her early twenties, she began a career as an anti-slavery lecturer and published her first collection of poetry, Forest Leaves. In 1853, in response to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper published a novel entitled Eliza Harris, which brought her national attention.

In 1860, she married Fenton Harper, but he died in 1864. She subsequently became the most widely published and recognized writer before and after slavery. Harper was also a teacher, an anti-slavery lecturer, a member of the Free Produce movement and, according to abolitionist William Still, one of the “ablest” workers on the Underground Railroad.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s body of work includes several collections of poetry. Among them are the following, published between 1872 and 1900: Sketches of Southern Life, Moses: A Story of the Nile, Light Beyond Darkness, The Sparrow’s Fall, Martyr of Alabama, Atlanta Offerings, and Poems. “The Slave Mother,” “The Slave Auction,” “The Fugitive’s Wife,” and “Bury Me in a Free Land,” are among her best known poems.

Harper was often characterized as “a noble Christian woman” and “one of the most scholarly and well-read women of her day,” but she was also known as a strong advocate for the abolition of slavery and the post-Civil War repressive measures against blacks. Three of F.E.W. Harper’s novels were serialized in the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s Christian Recorder: Minnie’s Sacrifice (1869); Sowing and Reaping: A Temperance Story (1876-1877), and Trial and Triumph (1888-1889).

In 1892, Harper’s best known novel was published: Iola Leroy: or, Shadows Uplifted. This was the story of a young woman striving to overcome racism during the Civil War and Reconstruction Eras.

After the Civil War, Harper continued a life of activism, promoting civil and women’s rights. She advanced these causes through her writing, through countless speaking engagements, and through her work with several organizations, including the American Equal Rights Association, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the YMCA, the National Congress of Colored Women, and the National Association of Colored Women, of which she was a founding member.

After the end of slavery and the American Civil War, a number of African-American authors wrote nonfiction works about the condition of blacks in the United States. Many African-American women wrote about the principles of behavior of life during the period. African-American newspapers were a popular venue for essays, poetry and fiction as well as journalism, with newspaper writers developing a large following.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Hannah Crafts

Wikipedia: Harriet E. Wilson

Wikipedia: African American Literature

New York Public Library: Frances E. W. Harper (1825-1911)

Digital Schomburg: African American Women Writers of the 19th Century