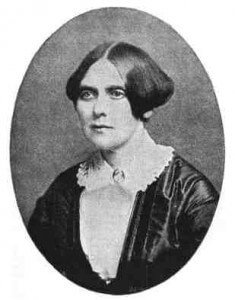

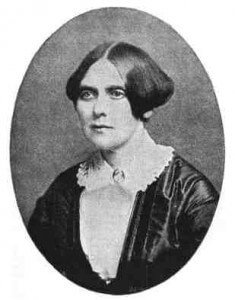

Abolitionist and Wife of William Lloyd Garrison

While her husband got all the glory, Helen Benson Garrison was an abolitionist in her own right. She raised funds for the American Anti-Slavery Society in many ways, particularly as a manager of the annual Boston Anti-Slavery Bazaar.

Helen Benson was born on February 23, 1811 in Providence, Rhode Island to George and Sarah Thurber Benson. At the June session of the General Assembly, in 1790, an “Act to incorporate certain Persons by the Name of the Providence Society for promoting the Abolition of Slavery, for the Relief of Persons unlawfully held in Bondage, and for improving the Condition of the African Race” was passed. Helen’s father, George Benson, became an active member of that society.

During his residence in Providence, Benson frequently sheltered slaves who were being pursued by slave traders or hunters. In the spring of 1824 he moved his family to Brooklyn, Connecticut, where he had purchased a farm near the center of the village. There, her father became president of the Windham County Peace Society, of which Samuel Sewell was secretary.

William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879) was an abolitionist leader who gained national prominence as an advocate of the immediate abolition of slavery. In 1830 Garrison was invited by Samuel May, his brother-in-law Bronson Alcott (father of Louisa May Alcott) and their cousin Samuel Sewell to lecture against slavery at a Connecticut church. In the audience was the lovely 19-year-old Helen Eliza Benson.

Benson and Garrison were introduced by mutual friends, and soon found they shared not only a profound belief in radical politics but also a deep mutual attraction. According to Garrison, “If it was not ‘love at first sight’ on my part, it was something very like it – a magnetic influence being exerted which became irresistible on further acquaintance.”

On January 1, 1831, Garrison published the first issue of The Liberator, in which he took an uncompromising stand for immediate and complete abolition of slavery in the United States. The paper became famous for its startling language. By January 1832, he had attracted enough followers to organize the New England Anti-Slavery Society which soon had dozens of affiliates and several thousand members.

In December 1833, Garrison and Arthur Tappan founded the American Anti-Slavery Society (AAS). The society’s activities frequently met with violence – mobs invaded meetings, attacked speakers and burned abolionist presses. In the mid-1830s, slavery had become so economically involved in the United States that getting rid of it would cause a major blow to the economy, especially in the South.

Many AAS affiliates were organized by women who responded to Garrison’s appeals for women to take active part in the abolitionist movement. The largest of these was the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, which raised funds to support The Liberator, publish anti-slavery pamphlets and conduct anti-slavery petition drives.

Marriage and Family

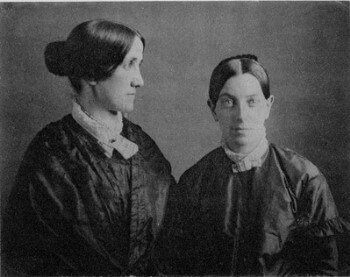

Helen Eliza Benson married William Lloyd Garrison on September 4, 1834. The couple had five sons and two daughters – a son and a daughter did not survive childhood. Their friend Rev. Samuel J. May officiated. By mutual agreement there was neither wine nor wedding cake for those who witnessed the ceremony; a bountiful dinner was served instead.

Helen’s marriage to Garrison enabled her to become more deeply involved in social reform activities. The Garrison household became known as an open-door salon for leftist political figures. Helen and her husband read and discussed political tracts (pamphlets) together, attended abolitionist meetings, and even ventured abroad on various human rights missions.

The threat posed by anti-slavery organizations and their activities drew violent reactions. In the fall of 1835, a mob of several thousand surrounded the building housing Boston’s anti-slavery offices, where Garrison was giving a speech to a meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. The mayor and police persuaded the women to leave the building, but the mob then began yelling for Garrison to be lynched or tarred and feathered.

The mayor managed to sneak Garrison out a window, but the mob pursued and captured him, tying a rope around his waist and dragging him through the streets of Boston. The sheriff rescued Garrison by arresting him and taking him to jail.

On another occasion, the following notice appeared in the Boston Transcript on September 17, 1835:

The residents in Brighton Street and vicinity were a good deal alarmed this morning on discovering a gallows erected in front of Mr. Garrison’s house, accommodated with cords, arranged with hangmen’s knots… It bore the superscription, ‘By order of Judge Lynch.’ It excited considerable curiosity and attracted a host of idlers, but occasioned no excitement, although it produced much merriment. It was taken down about half past ten, innocent of slaughter….

William Lloyd Garrison always had feminist leanings – early on insisting that sexual discrimination was as evil and pervasive as prejudice of the racial sort and that “universal emancipation” meant the redemption “of women as well as men from a servile to an equal condition.”

Anti-Slavery Work

Helen Garrison always invited to their home emerging individuals and groups in whom she had an interest, and through her, Garrison became acquainted with female abolitionists such as Lydia Maria Child and Abby Kelley, who became allied with him in the movement. More than an ordinary hostess, Helen always rolled up her sleeves and stuffed envelopes, edited tracts and raised funds for the cause.

In 1840, Garrison’s promotion of women’s rights within the anti-slavery movement caused some male abolitionists to leave the AAS and form the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which did not admit women. In June of that same year, when the World Anti-Slavery Convention meeting in London refused to seat America’s women delegates, Garrison refused to take his seat as a delegate and joined the women in the spectator’s gallery.

The controversy introduced the women’s rights question not only to England, but also to future women’s rights leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who attended the convention as a spectator with her husband, delegate Henry Stanton. Stanton was part of a group of abolitionists who disagreed with Garrison’s insistence that the U.S. Constitution was a pro-slavery document, and therefore abolitionists should not participate in politics and government.

A growing number of abolitionists – including Stanton and Amos Phelps – wanted to form an anti-slavery political party and seek a political solution to slavery. They withdrew from the AAS in 1840, formed the Liberty Party, and nominated James Birney for president. By the end of 1840, Garrison formed a third organization, the Friends of Universal Reform, with prominent reformers Maria Weston Chapman and Abby Kelley.

Although some members of the Liberty Party supported women’s rights, Garrison’s Liberator was the leading advocate of women’s rights, publishing editorials, speeches and legislative reports. In February 1849, Garrison’s name headed the women’s suffrage petition sent to the Massachusetts legislature – the first such petition sent to any American legislature – and he supported the subsequent annual suffrage petition campaigns organized by Lucy Stone and Wendell Phillips.

Critical at first of President Abraham Lincoln for making preservation of the union rather than abolition of slavery his chief aim during the Civil War, the Garrisons praised the President’s Emancipation Proclamation and supported his reelection in 1864. Many other abolitionists did not.

On December 4, 1863, Helen Garrison accompanied her husband to Philadelphia for the celebration of the thirtieth anniversary of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Helen was received affectionately by others in the movement. Her long hours of work had provided fresh funds for the abolitionist cause, particularly her service as one of the managers of the Boston Anti-Slavery Bazaar, year after year.

A few weeks later, on December 29, without warning, Helen suffered a stroke which paralyzed her entire left side and left her insensible and entirely helpless for a long period. Though still paralyzed, she later regained her faculties and enjoyed the remainder of her life as best she could.

On the advice of their family physician, they moved from Boston to Roxbury Highlands, three miles from the city. They found a beautiful home there and, sitting daily at the same window, Helen passed her days reading, writing letters and enjoying the visits of her numerous friends. Except for her paralysis, she enjoyed excellent health.

Late Years

With slavery abolished, William Lloyd Garrison announced in May 1865 he resigned the presidency of the AAS and offered a resolution to dissolve the society. Declaring that his “vocation as an Abolitionist, thank God, has ended,” he declined an appeal to continue. The AAS continued to operate for five more years, until ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted voting rights to black men.

He also ended publication of The Liberator, writing in his last editorial on December 29, 1865, in which he stated “the object for which the Liberator was commenced – the extermination of chattel slavery – having been gloriously consummated.” Retiring to Roxbury, he helped care for Helen and wrote weekly letters to his children.

Garrison continued to support reform causes, devoting special attention to rights for blacks and women. He contributed columns on Reconstruction and civil rights for The Independent and the Boston Journal, and in 1870, became an associate editor of the women’s suffrage newspaper the Woman’s Journal, along with Mary Livermore, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell.

After a severe cold worsened into pneumonia, Helen Benson Garrison died on January 25, 1876. A quiet funeral was held at home, but Garrison was confined to his bedroom with a fever and severe bronchitis, unable to join the service downstairs. This was the first fatal blow to his health. He recovered very slowly from the loss of his wife, and began to attend Spiritualist circles in the hope of communicating with Helen.

After Helen’s death, Garrison published a 32-page memoir Helen Eliza Garrison: A Memorial (1876). In thinking of their early years, Garrison wrote:

Even at this remote period, I confess that my emotional nature is powerfully stirred within me as I contemplate the loving trustfulness and moral courage exhibited by her in accepting my proffered hand and heart. For her own home was the abode of happiness and love… she was the specially favored one of the family, because the youngest daughter; all the comforts of life were abundantly assured to her; and her domestic and local attachments were exceedingly strong.

And what was my situation? I was struggling against wind and tide to maintain The Liberator; the chances of speedily realizing what are “the uses of adversity,” even as touching the ordinary

conveniences of life, were imminent. Moreover, for my espousal of the cause of the despised Negro, I was then universally derided and anathematized; I had the worst possible reputation as a madman and fanatic… and it was extremely problematical how long it would be before my abduction be effected by hired kidnappers… especially after the State of Georgia… offered a reward of five thousand dollars for my seizure and presentation within her limits.It is true, I was not without warm friends, genuine sympathizers, inestimable co-workers ; but, numerically, these were only as drops to the pouring rain, and, being themselves also under ban, could confer no credit and afford no protection.

The last paragraph in the book elegantly sums up the range of Helen Garrison’s interests and her role as a bridge between political movements:

At the annual meeting of the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association held in Boston, January 25, 1876, the following resolution was adopted: ‘Resolved, that the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association deeply sympathize with their honored friend William Lloyd Garrison on the death of his wife, which occurred this morning, and that they extend to him their warmest sympathy in his great bereavement.’

William Lloyd Garrison lived on until May 24, 1879.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: William Lloyd Garrison

Helen Eliza Garrison: A Memorial – PDF

Gale Encyclopedia of Biography: William Lloyd Garrison