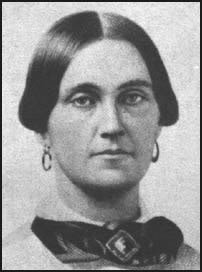

Daughter of Accused Lincoln Assassination Conspirator

Anna was only 22 years old when her mother Mary Surratt was sentenced to death as a conspirator in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. Despite Anna’s heartbreaking efforts to save her mother, Mary Surratt was hanged not quite three months after the assassination.

Anna was only 22 years old when her mother Mary Surratt was sentenced to death as a conspirator in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. Despite Anna’s heartbreaking efforts to save her mother, Mary Surratt was hanged not quite three months after the assassination.

Anna’s parents, Mary and John Surratt, were married in 1840, and lived on land John had inherited from his foster parents in what is now a section of Washington known as Congress Heights. John and Mary had three children: Isaac (born on June 2, 1841), Anna (January 1, 1843) and John Jr. (April 13, 1844).

When Anna was nine, her father purchased 287 acres of land that became known as Surrattsville (now Clinton). He opened a tavern that served as a polling place, post office and part time hotel. This became the destination for those wanting to discuss politics of the day. When the Civil War began in 1861 it was no secret that the Surratts favored the Confederacy.

The following year Anna’s father died suddenly and her mother Mary Surratt struggled with the debts left by her husband. Mary rented the tavern and farm to an ex-policeman named John Lloyd, and in October 1864 moved to the townhouse at 541 H Street in Washington, DC. To make money, Mary started renting rooms and soon turned the large residence into a boarding house.

The Assassination Plot?

During the Civil War, Anna’s brother John Surratt, Jr. became a Confederate spy and messenger. While engaging in these activities he met John Wilkes Booth, and early in 1865, Booth became a frequent visitor to the boarding house. Other people, later identified as Booth’s co-conspirators, also visited the boarding house regularly.

After President Abraham Lincoln was shot and Secretary of State William H. Seward stabbed on the night of April 14, 1865, authorities launched a massive manhunt for John Wilkes Booth and his conspirators. Within hours of the assassination detectives arrived at the Surratt boardinghouse. They searched the house and questioned all 13 people they found. Both Mary and her son John Jr. were suspected in connection with the murder, but John Jr. escaped.

Some months earlier, Booth had planned to kidnap Abraham Lincoln. In connection with that plot some of Booth’s co-conspirators had hidden two Spencer carbines in the joists of an unfinished loft in John Lloyd’s leased tavern. At midnight, after the assassination, Booth and David Herold stopped at the tavern to collect these items.

Arrest and Trial

On the night of April 17, 1865, Mary Surratt was arrested and charged with conspiracy, aiding the assassins and assisting in their escape, and allowing her boarding house to be used as a meeting place for Booth and his friends. Lewis Powell (alias Payne), a definite conspirator, came to her boardinghouse just as she was being arrested, which did not help her cause. She claimed she had never seen Powell before that night, but he had been there many times before the assassination.

Anna Surrat was accused of removing a picture from a mantel at the boarding house during the police search of the premises, on the back of which it was said she had hidden a photograph of John Wilkes Booth. Anna was also taken into custody that night and kept at the Old Capitol Prison until May 11 when she was released. She did not go back to the boarding house; instead she went to stay with friends.

Mary Surratt was also taken to the Old Capitol Prison. She remained there until April 30, when she was transported to the Washington Arsenal Penitentiary. It was in one of the administrative buildings at the Penitentiary that the assassination conspiracy trial was held. Anna visited her mother on many occasions; she also spent a lot of time talking with Lewis Powell, trying to convince him to help pursuade the court that her mother was innocent.

Since Lincoln had been Commander in Chief of the Army, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton declared the assassins should be tried by a military court. Although President Andrew Johnson, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and most of the Cabinet members disagreed, Attorney General James Speed agreed with Stanton.

Therefore, the defendants did not have the advantages of a jury trial, and were instead judged by a nine-member military commission. The trial began on May 9, 1865, and continued until the end of June. In court Mary Surratt was dressed in black, with her head covered in a black bonnet and her face mostly hidden behind a veil. She claimed total innocence of any part in the assassination plot. She said she knew nothing of Booth’s plans, and that her trips to Surrattsville had to do with collecting money she was owed by a man named John Nothey.

The prosecution’s strategy was to tie Mary Surratt to the conspiracy, and most of their case rested on the testimony of two men: her tenant at Surrattsville John Lloyd and one of her boarders Louis Weichman. Threatened with a murder charge and kept in solitary confinement, Lloyd and Weichman agreed to give evidence against Mary Surratt in return for their freedom. These men drew great criticism for their actions.

Weichmann’s testimony established an intimate relationship between Mary Surratt and the other conspirators, and the Surratt family’s ties to Confederate spy and courier rings operating in the area. Weichmann spoke respectfully of Mrs. Surratt and testified that he had resided at the boarding house since November 1864, and that he saw Booth give Mrs. Surratt a package of binoculars. Weichmann then drove her to the Surrattsville tavern on April 11 and April 14, the day of the assassination.

Mary Surratt’s fate was sealed by John Lloyd, who testified that she had requested that he have the field glasses and carbines ready for Booth and Herold when they arrived at the tavern late on the night of the assassination. Despite defense witnesses that attested to Surratt’s reputation as a gentle and deeply religious woman, Lloyd’s testimony was very damaging.

Anna, who seemed much younger than her age (22), testified at trial that it was Weichmann who had brought George Atzerodt into the boardinghouse, and that the photograph of Booth she had at the boarding house was hers (given to her by her father in 1862), and that she also owned photographs of Union political and military leaders. Anna denied ever overhearing any discussions of disloyal activities in the boarding house, and said that while Booth visited the house many times his stays were always short.

Mary Surratt was so ill the last four days of the trial that she was permitted to stay in her cell. The trial ended on June 28, 1865, and the court decided on the death penalty for Mary Surratt and her co-conspirators Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt and David Herold.

However, five of the nine judges signed a letter asking President Andrew Johnson to commute Mary’s sentence to life in prison, given her age and gender. Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt did not deliver the recommendation to President Johnson until July 5, two days before Surratt and the others were to hang. Johnson signed the order for execution, but did not sign the order for clemency. Johnson later said he never saw the clemency request; Holt said he showed it to Johnson, who refused to sign it.

Anna Surratt is remembered chiefly for her heartbreaking efforts to save her mother from being hanged by the U.S. government. After the guilty verdict, a tearful Anna tried to see President Andrew Johnson at the White House to plead for her mother’s life, but she was prevented from doing so. Adele Cutts Douglas, widow of Senator Stephen A. Douglas, went to see the president on Anna’s behalf, but was unable to change Johnson’s mind.

The Execution

General Winfield Scott Hancock, who had served in the Union Army, was in command at the Washington Penitentiary, where the defendants were being held. On the day of the execution, he stationed relays of cavalry all the way to the White House. If President Johnson changed his mind and granted a last-minute reprieve, the news would reach Hancock as soon as possible. No such reprieve came.

About midnight the friends and relatives of the prisoners began to arrive. All of the women were dressed in black, with heavy veils covering their faces. Anna was shown to her mother’s cell and remained there all night.

At exactly one o’clock in the afternoon the heavy door opening from the northwestern hall of the prison building into the court yard opened, and Mary Surratt came out, leaning upon two men – her spiritual advisors. She looked very pale as the men led her to the scaffold steps and she ascended, her hands manacled behind her. She sat on a chair placed at the northwestern corner of the scaffold, and the minister whispered words of comfort through the heavy black veil that covered her face.

On July 7, 1865, Mary Surratt was hanged, along with Powell, Atzerodt and Herold, thus marking the first time the U.S. government had executed a woman. There was no struggle on the part of Mrs. Surratt. Until the drop fell, a belief still existed that she would be reprieved, and if one had come even when the rope was around her neck, it would have surprised no one. Her last words on the scaffold were “Don’t let me fall.”

The Surratts were pariahs and society shunned them all. Except for a few family friends, Anna was now alone. Her younger brother John Surratt was still on the run as a purported Booth conspirator and her older brother Isaac who had been fighting for the Confederacy had yet to come home.

Anna never recovered from the traumatic events. Both of her parents were dead, one of her brothers was on the run and the other had not returned from serving in the Confederate army. Unable to bear living in the boarding house on H street, for the next few years Anna lived with various friends. Her mother had mortgaged the boarding house to pay her legal counsel. The house was sold in November 1867, and the property in Surrattsville was sold in March 1869.

Anna’s Life

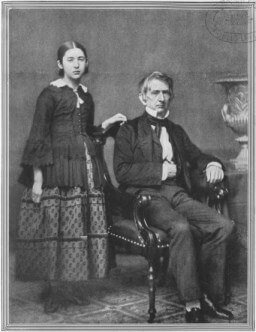

On June 17, 1869, Anna married William P. Tonry, a chemist working in the laboratory of the Army Surgeorn General. Ironically, his workplace was at Ford’s Theatre, which had been converted into government offices shortly after the assassination. The couple were married at St. Patrick’s Church a few blocks from Ford’s.

The ceremony was kept private, and there were no bridesmaids. Her brother Isaac was at Anna’s side, and John sat in a front pew. Just a few close friends were invited. This strict attention to privacy was to characterize Anna’s later years. The War Department fired Tonry five days after the wedding. Some believe he was dismissed for marrying Anna.

For a while the couple lived in poverty, but they eventually moved to Baltimore, where Tonry became a highly respected chemist. Their improving financial and social position relieved some of the strain in Anna’s life, but she continued to suffer emotionally and physically. Her hair turned white in her early thirties, and she remained subject to fits of extreme nervousness. Her brothers John and Isaac lived nearby, they gradually let the conspiracy issue rest.

During the 1880 presidential campaign, however the Republicans nominated James A. Garfield, and the Democrats chose Winfield Scott Hancock. Hancock’s connection with the Mary Surratt execution was used to try to turn voters against him. Swarms of reporters as well as a flood of letters and telegrams tried to draw out Anna’s opinion of Hancock, but she refused to make a statement on the matter. Hancock lost the election narrowly to Garfield, who was assassinated by a gunman a few months after being sworn in.

Anna and her family finally dropped out of the news, and Anna eventually had two more children. She was bedridden in her later years and died of kidney disease on October 24, 1904, at age 61. She was buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Washington, in an unmarked grave next to her mother.

Debate continues to this day as to whether Mary Surratt was actually involved in the assassination plot. Historical opinion is divided on the subject. It seems at least possible that Surratt knew about the plot to kidnap the president, but may not have known about the plan to assassinate him. Several good arguments for Mary’s innocence are made by Elizabeth Steger Trindal in her July 2003 article entitled The Two Men Who Held The Noose.

SOURCES

Mrs. Surratt’s Story

Wikipedia: Mary Surratt

Abraham Lincoln’s Assassination

Anna Surratt: Another Booth Victim

So what became of Anna Surratt’s children

none of the four hanged, shot the bullet that killed our beautiful abraham

lincoln. conspiracy to kill lincoln should have been punishment by

life in prison, perhaps, but not death to all four, especially a woman.

i honestly believe that mr. lincoln, himself, would have commuted

mary surratt’s sentence to one of prison. no excuse, for delaying the

untimely request to spare mary surratt of the hanging. scripture even

says, i will show you the same mercy you showed others. even the

slightest doubt should have prevented the hanging of a woman. shame

on the jurors and a president. the world was watching, i am certain!

God bless anna surratt, she suffered tremendously for the rest of her

life after the hanging of her mother.