Wife of Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas

Adele Cutts was a famous Washington beauty who became the loyal and valuable second wife of senator Stephen A. Douglas. She was at his side during the debates with Abraham Lincoln in Illinois and through the presidential campaign that followed in 1860.

Adele Cutts was a famous Washington beauty who became the loyal and valuable second wife of senator Stephen A. Douglas. She was at his side during the debates with Abraham Lincoln in Illinois and through the presidential campaign that followed in 1860.

Rose Adele Cutts was born in Washington, DC, in December 1835. Her father, James Madison Cutts, was a nephew of First Lady Dolley Madison. Her mother, Eleanora Elizabeth O’Neale, came from a prominent Catholic family in Maryland, and was the sister of Rose O’Neal Greenhow, who was later convicted of spying for the Confederacy.

Dolley Madison was very fond of James and Eleanora and was often seen in Washington, DC, proudly displaying little Adele Cutts at ceremonies she attended in the Capitol City. Dolley Madison’s Lafayette Square mansion became Adele Cutts’ second home.

Adele was educated at a Catholic academy in Georgetown. Adele grew up in Washington, where her good looks, winning personality, and impressive family connections made her a favorite of local society.

Stephen Arnold Douglas was born in Brandon, Vermont, on April 23, 1813. His parents were Stephen Arnold and Sarah Fisk Douglas. His father, a practicing physician, died when Stephen was an infant, and Stephen was educated in common schools, and completed his preparatory studies at Brandon Academy.

Young Stephen was ambitious, and anxious to get a good education so he could provide for himself and his family. In 1828, at the age of 15, he was apprenticed to a cabinet maker, hoping to make enough money to allow him to go to college. It was during this year that he became politically inspired during the campaign of General Andrew Jackson, and Douglas became a life-long Democrat.

Two years later his family moved to Canandaigua, New York, where he was able to study at the Canandaigua Academy until December 1832. He began to study law at the Academy, but ran out of money and did not make any further attempts at a formal education.

Stephen decided to go west, and on June 24, 1833, he left for Cleveland, Ohio, where he was dangerously ill with fever for four months. He then visited Cincinnati, Louisville, St. Louis, and Jacksonville, Illinois, but failed to get a job. After his money exhausted, he walked to Winchester, Illinois, where he arrived at night with only thirty-seven and a half cents.

There he secured three days’ employment as clerk to an auctioneer at an administrator’s sale. He made such a good impression that he got a job teaching school for about forty pupils, whom he taught for three months. During this time he studied law at night, and on Saturdays practiced before justices of the peace.

Early Political Career

In March 1834, Stephen Douglas moved to Jacksonville, Illinois, obtained his license, and began to practice law. He was so successful there that a year later he was a leader in the state’s Democratic party, and was elected as State Attorney for Morgan County, Illinois – all by the time he was twenty-two years old.

In December 1835, he was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives, where he was the youngest member. The mental vigor he displayed there, in striking contrast with his physical frame, which was then very slight, won for him the title of the Little Giant. He was only 5 feet 4 inches tall, and weighed a little over ninety pounds, but he had broad shoulders and a barrel shaped chest.

In December, 1840, Douglas was appointed Secretary of State of Illinois, and in the following February was appointed in 1841 an associate justice of the Illinois Supreme Court in 1841, at age 27. He was elected twice to the U.S. House of Representatives (1842 and 1844). The all-consuming issue of the era was slavery. Douglas opposed slavery, he advocated states’ rights.

Marriage and Family

In Illinois Stephen Douglas courted Mary Todd – who eventually married Abraham Lincoln – and in 1847 Douglas married Martha Martin. After giving birth to a daughter in January 1853, Martha died.

Tall, with chestnut hair, and universally acclaimed beauty, Adele “Addie” Cutts was twenty years old when she met Stephen Douglas in 1856, when he had narrowly lost the Democratic presidential nomination to James Buchanan. Though he was more than twice her age, they only courted briefly.

Stephen Douglas and Adele were married in Washington in November 1856. Adele immediately took over the management of the Senator’s household, accepted the two Douglas boys as her own, and, with Douglas’ approval, had his sons raised and educated as Catholics. She had a transforming effect on the somewhat disheartened Illinois senator.

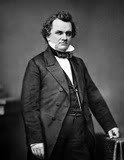

Image: Senator Stephen A. Douglas

Image: Senator Stephen A. Douglas

In 1857 Stephen and Adele built a mansion with a ballroom. Under Adele’s direction, the richly decorated Douglas mansion quickly became the center of the Washington social scene. She was indisuptably the belle of Washington – beautiful, warm-hearted, and universally loved and admired. Together they commanded substantial political power.

A gala housewarming party in January 1858 attracted as many as 2000 visitors. A year later, a grand ball at the Douglas mansion left nearby streets so jammed with carriages that guests had to walk several blocks to reach the front door.

The Douglases shared an unusually close and empathetic relationship, particularly in times of trial. When Adele suffered a miscarriage in February 1858, she was so weakened that for several days doctors feared for her life. In the following weeks, Stephen himself became seriously ill and briefly abandoned his senatorial obligations.

The next year, after giving birth to a daughter, Ellen, who lived only a few weeks, Adele once more became desperately ill. Her health began to improve, but then Stephen succumbed to illness, and the two shared weeks of convalescence.

Stephen Douglas was first elected to the U.S. Senate in 1846. When the U.S. victory in the Mexican War reopened the issue of slavery in the late 1840s, two opposing viewpoints clashed: the Southern view that slavery should be allowed to expand into the newly acquired territories; while the Northern view was that the federal government could ban slavery in these areas.

Douglas tried to take a middle path: let the settlers vote whether to allow slavery or not, a concept called popular sovereignty. This was applied to the territories of Utah and New Mexico with the Compromise of 1850, which Douglas chiefly designed. The omnibus bill containing it did not pass Congress.

As chairman of the Committee on Territories, Douglas dominated the Senate in the 1850s. In 1854 he set off a tremendous political upheaval when he introduced his Kansas-Nebraska Act to the Senate. He argued that the people of the territory should decide the slavery question by themselves, and that soil and climate made the area unsuitable for plantations; which reassured his northern supporters it would remain free.

Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln aired their disagreement on this topic in Peoria, Illinois, on October 16, 1854. Although Mr. Lincoln’s three hour speech presented thorough moral, legal and economic arguments against slavery, it did not stop the Act from passing. It passed because of Southern votes, and Douglas had little to do with the final text of the bill.

Lincoln – Douglas Debates

In 1858, Abraham Lincoln, the Republican candidate, challenged Stephen Douglas for his seat in the U.S. Senate in a series of seven nationally famous debates on the issue of slavery – the first on August 21 and the last on October 15. During the debates, Adele traveled with her husband through Illinois.

During the debates, each three hours long, Douglas attempted to brand Lincoln as a dangerous radical who advocated racial equality. Douglas repeatedly invoked racist rhetoric, claiming Lincoln was for black equality, and saying at Galesburg that the authors of the Declaration of Independence did not intend to include blacks.

Whereas Lincoln concentrated on the immorality of slavery and attempts to restrict its growth. He was opposed to Douglas’ proposal that the people living in the Louisiana Purchase (Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Iowa, the Dakotas, Montana, and parts of Minnesota, Colorado and Wyoming) should be allowed to own slaves. Lincoln argued that the territories must be kept free for “poor people to go and better their condition.”

Lincoln advocated equality of opportunity, arguing that individuals and society advanced together. Douglas, on the other hand, embraced a democratic doctrine that emphasized equality of all citizens (only whites were citizens).

The second debate, held at Freeport, Illinois, on August 27, 1858, had the most important consequences. There Lincoln shrewdly put to Douglas a question exposing the inconsistency between Douglas’ doctrine of popular sovereignty and the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in the Dred Scott Case: “Can the people of a United States Territory, in any lawful way… exclude slavery from its limits prior to the formation of a State constitution?”

Had Douglas answered no, in line with the Dred Scott decision, he would have offended many of his constituents and doubtless lost his seat in the Senate. As it was, he replied that people of a territory could exclude slavery, since that institution could not exist for a day without local police regulations and these could be legislated only with their approval.

The Republicans won a popular majority in the 1858 election, but the Democrats controlled the legislature, and Douglas was returned to the Senate. However, his Freeport Doctrine, as his answer to Lincoln’s question became known, had cost him the support of the Southern Democrats. Since they controlled the Senate, he was relieved of the chairmanship of the Committee on Territories.

Adele also accompanied Douglas through his travels during the 1860 presidential campaign. At the Democratic Convention in Charleston in April 1860, the delegates were deeply divided. Most from the Deep South argued that the Congress had no power to legislate over slavery in their territory. The Northerners disagreed and won the vote. As a result the Southerners walked out and held another meeting in Baltimore. Again the Southerners walked out over the issue of slavery. With only the Northern delegates left, Douglas won the nomination.

Southern delegates then held another meeting in Richmond, and Vice President John C. Breckinridge was selected as their candidate. The situation was further complicated by the formation of the Constitutional Union Party and their nomination of John Bell of Tennessee.

The Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln won the election with 1,866,462 votes (18 free states) and beat Douglas (1,375,157 – 1 slave state), John C. Breckinridge (847,953 – 13 slave states) and John Bell (589,581 – 3 slave states). Between election day in November 1860 and inauguration the following March, seven states seceded from the Union: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas.

When the Civil War broke out, Douglas vigorously supported Lincoln. Douglas rallied his supporters to the Union with all his energies. In late May, the unrelenting strain of the past year caught up with Douglas. After an eloquent speech at Springfield, he was stricken with fever and declined rapidly. His last words to his children were, “obey the laws and support the constitution of the United States.”

Senator Stephen A. Douglas died in Chicago on June 3, 1861, at the age of 48.

The spot on the banks of Lake Michigan in Chicago that Douglas had reserved for his future home was bought by the state. The following October, a group of his friends and associates organized the Douglas Monument Association. Sculptor Leonard Volk, a relative of Douglas by marriage, presented a plan for an eighteen-member board of trustees and served as the Association’s secretary.

The Association invited President Andrew Johnson to participate in the cornerstone laying ceremony. He accepted and stopped in Chicago as part of his political tour of the eastern half of the country. Accompanying Johnson were several members of his cabinet, as well as Generals Grant, Rawlins, Dix, Meade and Custer, and Admiral Farragut.

The ceremony took place on September 6, 1866. Shops, businesses, and banks were closed. The Illinois Central Railroad ran trains to the grave every ten minutes. Over one hundred thousand people lined the parade route.

In spite of mourning her husband’s death, Adele Cutts Douglas and her mother Eleanor Elizabeth O’Neale Cutts volunteered their services in DC hospitals.

Five years after Stephen Douglas’ death, Adele remarried Captain Robert Williams, a career army officer from Virginia who had remained loyal to the Union. She took on the life of an army wife, and raised their six children in the western territories. Williams ended his long career in 1893 as Adjutant General of the Army.

Adele Cutts Douglas Williams died at her home in Washington on January 26, 1899, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

SOURCES

Stephen Douglas

Great Lives in History

Wikipedia: Stephen A. Douglas

Answers.com: Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen A. Douglas and the American Union