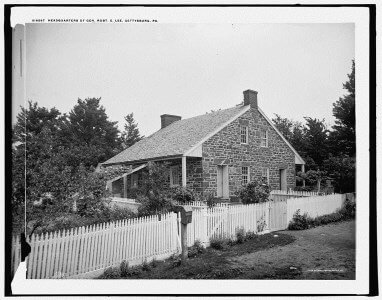

Home Used as Union Headquarters at the Battle of Gettysburg

On July 1, 1863, Federal troops surrounded the Leister farm – it was in the crook of the fishhook battle line along Cemetery Ridge. When General George Gordon Meade chose the Leister house (image left) as the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac, Lydia and her children sought shelter with relatives who lived on the Baltimore Pike.

On July 1, 1863, Federal troops surrounded the Leister farm – it was in the crook of the fishhook battle line along Cemetery Ridge. When General George Gordon Meade chose the Leister house (image left) as the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac, Lydia and her children sought shelter with relatives who lived on the Baltimore Pike.

Lydia Leister was a widow who owned a modest farm along the Taneytown Road, ½ mile south of Gettysburg behind Cemetery Ridge. Lydia had purchased the property in 1861, and moved into the modest two-room house with her six children, the youngest, only three years old. The widow Leister made her living by working her 9-acre farm that included a small barn, an orchard, and a vegetable garden.

The Battle

As the last shots faded on the night of July 2nd, a contingent of weary officers rode into the Leister yard. Stamping the mud from their boots on the porch, the officers entered the small room lit only by several flickering candles. Seated at the table to make notes was Major General Daniel Butterfield, Meade’s chief of staff. Meade’s generals took seats around the room.

The discussion continued for several minutes until General Butterfield suggested that the question be formally asked to the members of the council. Three questions were asked, including whether the army should remain at Gettysburg or retire to a better position, wait for Lee to attack or attack him, and how long should the army wait before striking Lee?

Almost to a man, the officers agreed to correct any awkward positions in the line and remain on the field for another day. Due to the heavy casualties in three of Meade’s army corps, they deemed it best to wait for Lee to attack before moving against him. The last officer to comment, General Henry Slocum, put it quite succinctly: “Stay and fight it out!”

Junior in rank to the other officers in the room, General John Gibbon had listened carefully to the discussion of each corps commander. As the officers prepared to leave, Meade suddenly confronted Gibbon, saying:

“If Lee attacks to-morrow, it will be on your front.” I asked why he thought so and he replied, “Because he has made attacks on both our flanks and failed, and if he concludes to try it again it will be on our center.” I expressed the hope that he would, and told General Meade, with confidence, that if he did we would defeat him.

Meade’s words were prophetic. Lee did attack the Union center on July 3rd, in what has become known as Pickett’s Charge, the greatest charge of the Civil War.

The Aftermath

Lydia returned home to find her yard littered with dead soldiers and dead horses, and her house riddled with artillery shells. Her livestock was gone, and her crops trampled. Her fences were knocked over and the garden trampled. Her food stores had been raided by hungry staff officers and headquarters guards, and some of her furniture dragged into the yard for use as writing desks.

The farmers surrounding the town of Gettysburg fared no better than the townspeople — and, in many cases, suffered more damage to their property.

Nearby free black farmer Abraham Brian suffered similarly. Brian had left Gettysburg when word of the approaching Confederates reached him, and returned to find his fences gone, his crops destroyed, and his house riddled with bullets.

William and Adelina Bliss, whose farm lay between the opposing forces on Seminary Ridge and Cemetery Hill, evacuated so quickly on July 1 that they left the doors open, the table set, and the beds made. Their home was burned to the ground by Union troops on July 3 to prevent its use as a haven for Confederate sharpshooters.

The Recovery

After the Union dead were buried, it would take two more days to bury the Confederate dead. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of horses, mules, and livestock were rotting on the battlefield. They had to be disposed of, too.

Photographs taken after the battle showed a large number of dead horses in the small garden at the Leister farm. They had been slaughtered by Confederate artillery that had overshot its intended target on Cemetery Ridge. The horses died by the dozen on the reverse slope. Lydia burned their bones, and sold the ash/bone mix as fertilizer. She made about $30.

Many of the farmers filed claims with the Federal government after the battle, but few received much, if any, restitution for the devastation they suffered.

Lydia received no compensation for the damage done to her property, but managed to prosper after the war. She purchased seven more acres of land in 1868, and built a large two-story addition onto the house in 1874.

In 1888, at the age of 79, Lydia sold her farm to the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association and moved into the town of Gettysburg. Later, she purchased a lot near the Dobbin House on the Emmitsburg Road, and moved the 1874 section of her previous home to that site.

She then built a two-story addition onto the rear of her home, where she lived until her death in 1893.

SOURCES

The Council of War

Leister House History

Gettysburg Photo Album