Farm on the Gettysburg Battlefield

John Slyder married Catherine Study in Carroll County, Maryland on September 25, 1838, and the couple soon moved to Gettysburg. In the 1840s the Slyders resided on South Washington Street in town, and John went into business with a local potter named Edward Menchey.

John Slyder married Catherine Study in Carroll County, Maryland on September 25, 1838, and the couple soon moved to Gettysburg. In the 1840s the Slyders resided on South Washington Street in town, and John went into business with a local potter named Edward Menchey.

An 1847 an advertisement in the Adams Sentinel also listed Slyder’s house as a pick-up and drop-off location for a woolen manufacturing business. Citizens looking to have woolen goods manufactured at a factory located 3 miles outside of Hanover could drop off their own wool at Slyder’s residence and pick up the finished product at a later date.

In 1849, the Slyders purchased a 74-acre tract of land at the foot of Big Round Top and along the banks of a small stream known as Plum Run, three miles south of Gettysburg, and began to make a working farm out of it. By 1852, they had on the premises a two-story stone house and several outbuildings: a double-log barn, summer kitchen and woodshed, hog pen, privy, chicken house, smokehouse, and blacksmith and carpenter shops.

Around this time, John and Catherine moved out of the borough and down to the farm permanently. Throughout the 1850s the Slyders farmed the land and maintained orchards of peach and pear trees, thirty acres of timber and eighteen acres of meadow. John Slyder also manufactured iron tools and implements for neighboring farmers in his blacksmith shop.

The Gettysburg newspapers from the 1850s show that John Slyder was an involved and respected member of the community. His name appeared several times as a witness to the good character and morals of other locals applying for permits to run boarding houses or taverns. In 1852 his neighbors in Cumberland Township elected him to the post of inspector.

In the summer of 1863, John and Catherine Slyder lived on the farm with their three youngest children: John, age 20, Hannah, age 17, and Jacob Isaiah, age 9. Their two older children had moved away to homes of their own.

In the two years that the war had been going on, the fighting had taken place in the states that were trying to secede from the Union. Still, there were some signs that trouble might come their way. On June 30, 1863, some Union soldiers had come to the farm asking for food and water. Catherine Slyder had just baked bread and had picked some beans from her garden. Nervous about what might happen if the family did not cooperate, she gave those to the soldiers and sent them on their way.

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee began moving his army north in early June 1863, hoping to find desperately needed supplies in the rich Pennsylvania farmlands. Lee reasoned that a decisive victory in the North would increase pressure on the United States government to seek a peace agreement with the Confederacy. Thus, Lee and his army moved into Pennsylvania during June and eventually converged in Chambersburg, 22 miles west of Gettysburg.

Day 1

Neither General Lee nor General George Gordon Meade, commander of the Union Army of the

Potomac, had anticipated a battle at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, but chance brought the two forces together. This first day’s battle was a victory for the Confederates. They came with greater numbers initially from the west and the north, pushing the Union forces back through town. The Union troops retreated but regrouped on the high ground south of town and formed a long defensive line shaped like a fishhook.

Day 2

For the Slyder family, July 2, 1863 probably started out like any other summer day. There was always something to do on a farm – and the Slyders, like most farmers of the time, grew or made almost everything they needed to survive. Now their farm, on the western edge of Big Round Top, was located at the southern end of what would become the battlefield later that day.

Early in the morning, Union soldiers on horseback arrived at the farm. “You’d better leave,” they told the Slyders. Confederate forces were assembling along Emmitsburg Road -just a few hundred yards from their property. On the other side of their farm, Union soldiers were gathering at Devil’s Den. The Slyders had to make a decision – should they stay or should they go? Ultimately, they decided it was in the best interest of their family to leave.

On the morning of July 2, the Union line of battle began to stretch closer and closer to the Slyder farm. The area became more active as Union General Daniel Sickles was deploying his III Corps at the extreme left end of the Union line of battle. Contrary to orders from Commander-in-Chief General George Meade, at about noon Sickles began moving his men farther forward than the rest of the line, creating a salient that could be attacked from three sides.

Berdan’s Sharpshooters

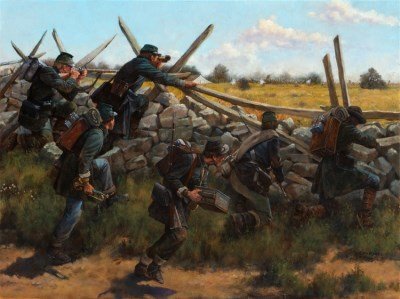

At about 2 p.m. an elite regiment of the Army of the Potomac arrived: Colonel Hiram Berdan’s expert marksmen, the 2nd United States Sharpshooters (U.S.S.S.). Popularly known as Berdan’s Sharpshooters, these expert marksmen wore distinctive uniforms: dark green frock coats, trousers and caps, and leather leggings.

The 2nd U.S.S.S. formed a thin, extended line running perpendicular to the Emmitsburg Road, with some of the men being posted in the fields of John Slyder’s Farm, west of Big Round Top, taking advantage of the stone walls bordering his farm lane and the fences in his fields. Here the sharpshooters prepared to defend the Army of the Potomac’s left flank and the approaches to Big Round Top.

By 4 p.m. Confederate infantry and artillery from CSA General James Longstreet‘s First Corps began to take positions along Warfield and Snyder rigdes near the Emmitsburg Road, and the 2nd U.S.S.S. skirmish line was the first line of defense against the Confederate onslaught of General John Bell Hood‘s division as it swept across the Slyder farm. As the waves of butternut clad rebels advanced, they provoked a steady response of well-aimed shots by the green jackets.

Berdan’s Sharpshooters took position in the angle of a stone wall that ran between the two story farmhouse and the barn, and opened fire upon the enemy. As the Confederate skirmish line came closer, firing intensified. Though they were severely outnumbered by the oncoming Confederates, the Federals’ breech loading 52 caliber Sharps rifles allowed for rapid and accurate fire.

Berdan’s Sharpshooters took position in the angle of a stone wall that ran between the two story farmhouse and the barn, and opened fire upon the enemy. As the Confederate skirmish line came closer, firing intensified. Though they were severely outnumbered by the oncoming Confederates, the Federals’ breech loading 52 caliber Sharps rifles allowed for rapid and accurate fire.

Image: Berdan’s Sharpshooters at Slyder’s Farm by Keith Rocco

From their protective cover behind the stone wall and other favorable positions, the sharpshooters were able to harass and delay the Confederate deployment. According to an officer in General Evander M. Law’s Alabama Brigade, they ran into a “perfect hornet’s nest of sharpshooters” at the Slyder Farm. The rebels were thus slowed, and many fell dead along the way.

The sharpshooters continued firing until the rebels were within a hundred yards of them. They were then ordered to fall back, as their right was outflanked by the extended Confederate line of battle. Laws’ men overran the farm, trampling the crops and fields in their wake. The sharpshooters continued to fire as they made their retrograde movement, and then withdrew over Big Round Top.

The Sharpshooters’ cunning tactics and incredible marksmanship delayed and disorganized Hood’s attack on July 2, buying much-needed time for Union officers to reinforce their weakened left flank. As the battle washed over Slyder Farm, the house, barn and other outbuildings became aid stations where wounded soldiers of both sides received treatment before being moved to the rear.

Day 3

The farm remained behind Confederate lines on July 3. On July 3, General Lee again attacked the Union forces, but this time he struck at the center of the Union line since the fighting on the previous day had demonstrated the strength of the Union flanks. In this massive assault, now popularly known as Pickett’s Charge, the Confederates attacked Union troops on Cemetery Ridge. But the Union Soldiers held once again and pushed the Confederates back to their original position on Seminary Ridge, thus ending the Battle of Gettysburg.

South Cavalry Field

In addition to the famous cavalry action at the East Cavalry Field on the afternoon of July 3 involving Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart‘s troops and Union General David M. Gregg’s troops that included General George Armstrong Custer, there was another charge later that day in the area of the John Slyder farm.

After Pickett’s Charge had been repulsed, Union cavalry commander General Judson Kilpatrick ordered General Elon Farnsworth to launch a mounted attack against the right flank of the Confederate Army near the base of Big Round Top and the John Slyder farm on the afternoon of July 3. Farnsworth and his men questioned whether a cavalry charge over such rocky and difficult terrain could be successful.

General Kilpatrick (often referred to as Kill Cavalry because of his lack of concern for the lives of his men) reportedly responded by saying that if General Farnsworth would not lead the charge, then he himself would lead it. His bravery now in question, General Farnsworth personally lead the third and last wave of the assault with approximately 300 men of the 1st Vermont Cavalry Regiment.

Farnsworth rode with Major William Wells, who commanded a battalion of the 1st Vermont Cavalry Regiment. Wells’ men knifed through the skirmish line of the 47th Alabama, entered the meadow of the Slyder farm and then followed a low stone wall east to a spur of Big Round Top. When the column reached the spur, Farnsworth led it north through the woods in the rear of the Alabama regiments posted at the foot of Big Round Top.

Wells’ horsemen cleared the treeline into fields west of Devil’s Den and Houck’s Ridge, but to their right a brigade of Georgians turned toward the Federals, pelting them with musketry. A Confederate battery on Emmitsburg Road burst shells above the Vermonters. Farnsworth’s horse was killed, and a corporal gave his mount to the general. Caught in a circle of hellfire, the battalion splintered into three groups.

The final group, led by Farnsworth and Wells, retraced their route toward the spur of Big Round Top. The woods swarmed with Rebels, and gunfire sang through the column. The 15th Alabama came rushing into line as the Federals re-emerged into a field, and the skirmishers of the 47th Alabama took aim.

Squadrons from other commands raced to the aid of Wells’ men, but time had run its course for the bloodied Vermonters. A scissors of musketry cut into the ranks of Wells’ column. Farnsworth reeled in the saddle and fell mortally wounded, struck in the chest, abdomen and leg by five bullets. The surviving Vermonters slashed their way through the ring of Confederates with their sabers. Wells led one party to safety and would earn the Medal of Honor for his actions.

A monument to the 1st Vermont Cavalry Regiment stands in what is called the D-shaped field on the Slyder farm. This is the approximate location where official accounts reportedly indicate that General Farnsworth was killed, while receiving the fire of five Confederate regiments and two batteries.

Aftermath

The Slyders returned to find a destroyed farm, and their possesions looted or spoiled, leaving them with little means to feed themselves for the rest of the year. Thousand of soldiers had trampled their crops, filched the fruit from the orchards, dug up the garden in search of food, and drank up the water in the well.

Image: The Slyder house as it appeared in 1935

Image: The Slyder house as it appeared in 1935

Though they submitted a claim to the U.S. government, the Slyder family never received reimbursement for their destroyed his fields, crops and livestock. Few Gettysburg civilians did. Instead, they were left on the verge of bankruptcy. The decided to sell the farm and move to Ohio.

The Slyder family had connections with other Gettysburg families: Catherine Slyder was the sister of Lydia Leister, whose home had served as headquarters of Union General George Meade during the battle. And in October 1863, the Slyders’ son William married Josephine Miller, granddaughter of Peter and Susan Rogers, who owned a farm on Emmitsburg Road. By then the Slyders had sold the farm and moved to Ohio.

SOURCES

Free Republic: Elon John Farnsworth

Berdan’s Sharpshooters at Slyder Farm

Battle of Gettysburg Buff: South Cavalry Battlefield

Battlefield Back Stories: Remembering Where We Are