Farm on the Gettysburg Battlefield

Gettysburg farmer James Leister died in 1859, leaving his wife Lydia Leister and five children, ranging in age from 21 to 3. In March 1861, the widow Leister purchased a nine acre farm on Taneytown Road from Henry Bishop, Sr. for the sum of $900. The property included a modest, wood frame house with a single fireplace, two rooms and a stairway that lead to a small loft.

Gettysburg farmer James Leister died in 1859, leaving his wife Lydia Leister and five children, ranging in age from 21 to 3. In March 1861, the widow Leister purchased a nine acre farm on Taneytown Road from Henry Bishop, Sr. for the sum of $900. The property included a modest, wood frame house with a single fireplace, two rooms and a stairway that lead to a small loft.

Image: Restored Lydia Leister Farm today

Looking north along Taneytown Road

After the strong Confederate win at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863 CSA General Robert E. Lee effectively argued that the best use of limited Confederate resources was to invade Pennsylvania. In early June he began moving his army north, hoping to find desperately needed supplies for his army in the rich Pennsylvania farmlands.

July 1, 1863

Neither General Lee nor USA General George Gordon Meade had anticipated a battle at Gettysburg. The two armies were operating in ignorance of the other’s location but on June 30, both commanders ordered their forces to converge on Gettysburg. On the morning of July 1, General John Buford‘s cavalry were awaiting the approach of Confederate infantry forces coming from the direction of Cashtown to the northwest.

In July 1863, the widow Leister was making her living by working her small farm, which included a log barn, a hayfield, several apple and peach trees, and a vegetable garden. As word spread of the approaching Confederate Army, she vowed that she would not give up her farm. However, once the battle was on, she sought shelter with relatives on the Baltimore Pike for the safety of her children.

This first day of the battle was a victory for the Confederates. They came with greater numbers initially from the west and the north, pushing Union forces back through the town of Gettysburg. However, officers wisely directed their men to occupy the high ground south of town – on Culp’s Hill, Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge and Little Round Top. There they formed a long defensive line shaped like a fishhook. It would be extremely difficult to dislodge them from those heights.

Army of the Potomac Headquarters

As the last shots of the first day’s battle on July 1, 1863 faded and night began to fall, a contingent of weary officers rode into the yard of Lydia Leister’s home and found it vacant. Situated on the Taneytown Road on the reverse slope of Cemetery Ridge just inside the fishook curve of the Union line made this humble home a perfect location for the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac. These men, staff officers of General George Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, secured it as their headquarters.

July 2, 1863

On July 2, the Confederates struck both ends of the Union line.They hit hard, first at Little Round Top and then at Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill; but with high ground and numerous craggy rock formations in their favor, Union troops held strong against these attacks. Confederate forces fell back and formed along Seminary Ridge again.

By the evening of July 2, the Widow Leister’s stone and rail fences had been partially knocked over and the garden trampled by the passage of courier’s horses. Her food stores had been raided by hungry staff officers and headquarters guards, and some of her furniture dragged into the yard for use as writing desks. This home would play host to one of the most important meetings of the battle.

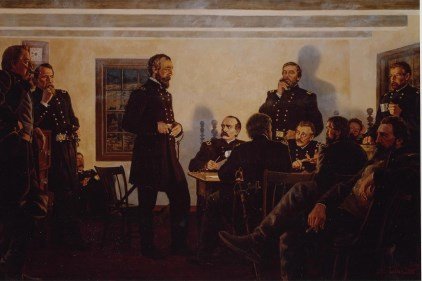

General Meade’s Council of War at the Leister House

On the evening of July 2, 1863, General Meade held a famous council of war in the Leister home. Seated at the table to make notes was General Daniel Butterfield, Meade’s chief of staff. General by general, Meade’s commanders stepped into the small candlelit room: John Newton, commander of the First Corps since the death of General John Reynolds on July 1; John Gibbon, in charge of the Second Corps; David B. Birney, in command of the Third Corps after the wounding of General Daniel Sickles.

Also present were General George Sykes, whose Fifth Corps had seen so much of the fighting that day; John Sedgwick of the newly arrived Sixth Corps; O.O. Howard of the Eleventh Corps; Alpheus Williams of the Twelfth Corps; Henry Slocum, a dedicated officer who believed in standing one’s ground; and Winfield Scott Hancock, whose command decisions had saved the day on the Union left. Also present was an exhausted Gouverneur Warren, “Savior of Little Round Top,” who slumped to the floor and fell asleep as the meeting began.

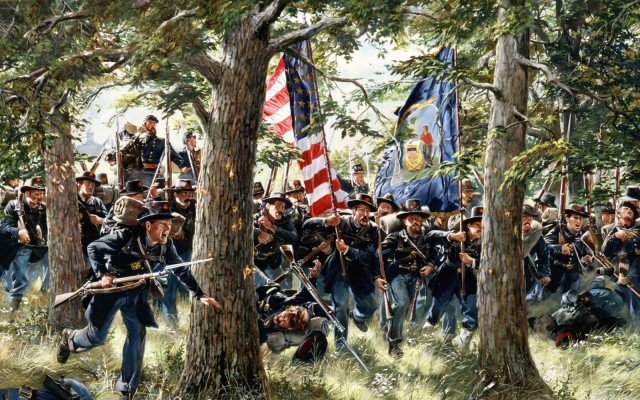

Image: Stay and Fight it Out by Don Stivers

Image: Stay and Fight it Out by Don Stivers

On the night of July 2, 1863, General George Meade met with his corp commanders in a council of war at the Leister house to find out what condition his army was in and whether they should continue the battle. This pivotal meeting was held in the small quarters of the Leister farmhouse on Cemetery Ridge.

Despite a severe battering the Army of the Potomac still held all the key terrain on the battlefield. The question at hand was could they stand another day, and was Gettysburg the place to continue the battle? General George Meade, who had only been in command of the Army of the Potomac for only five days, wanted information from his corps commanders concerning both the army’s condition and their thoughts about its position.

Lieutenant Frank Haskell, aide to Brigadier General John Gibbon, who attended the council as the acting corps commander of the 2nd Corps, wrote:

The Generals came in – some sat, some kept walking or standing, two lounged upon the bed, some were constantly smoking cigars. And thus disposed, they deliberated whether the army should fall back from its present position to one in rear which it was said was stronger, should attack the enemy on the morrow, wherever he could be found, or should stand there upon the horse-shoe crest, still on the defensive, and await the further movements of the enemy.

General Meade listened intently as his corps commanders reported the conditions of their respective fronts and expressed opinions on what the Confederates may be devising for the following day. Due to the heavy casualties already sustained, all agreed that they should wait for General Lee to attack them. Finally, General Slocum boldly stated, “Stay and fight it out!”

July 3, 1863

On July 3, the Leister farm was immediately behind the point of the attack during a four hour cannonade by Confederate artillery, during which the Leister house was deluged with numerous overshoots. One shell burst among the staff horses in the yard, while others carried away the steps and porch supports of the widow Leister’s home. Flying splinters became dangerous.

When Meade saw some members of his staff favoring the down range side of the flimsy house, the fearless, twice-wounded Meade joked with them about their imaginary shelter. But for the sake of efficiency he eventually moved his staff a few hundred yards away to a nearby barn. When it, too, proved to be a target, they moved on to the 12th Army Corps Headquarters on Powers Hill, which was part of the Union Army’s series of signal stations.

General Lee had previously attacked both Union flanks of the Union line with success. On July 3, he attacked the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge in what became known as Pickett’s Charge. This excerpt from The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz describes the Charge as General Carl Schurz observed it from the crest of Cemetery Hill:

And then came forth that famous scene which made the battle of Gettysburg more dramatic than any other event of the Civil War, and which more nearly approached the conception of what a battle is in the imagination of persons who have never seen one. I will describe only what we observed of it from the crest of Cemetery Hill.

From a screen of woods opposite our left center emerged a long line of Confederate infantry, mounted officers in front and behind; and then another, and another – about 15,000 men. The alignment was perfect… A mile of open field separated them from our line of defense. They had hardly traversed one-tenth of that distance when… our batteries… opened upon them from the front and from the right and left, with a terrific fire.

Through our field-glasses we could distinctly see the gaps torn in their ranks, and the ground dotted with dark spots – their dead and wounded. Now and then a cheer went up from our lines when our men observed some of our shells striking right among the advancing enemy and scattering death and destruction around.

Then the Confederate artillery behind them, firing over their heads, tried to silence our batteries or at least to attract their fire so as to divert it from the infantry masses advancing in the open field. But in vain. Our cannon did not change their aim, and the number of dark spots dotting the field increased fearfully from minute to minute. So far not a musket had been discharged from behind the stone fences protecting our regiments.

Now the assailants steadily marching on seemed to disappear in a depression of the ground, where they stopped for a little while to readjust their alignment. But when they emerged again, evidently with undismayed courage, and quickened their pace to make the final plunge, a roar of cannon and a rattle of musketry, so tremendous, received them that one might have thought any force coming against it would have been swept from the face of the earth.

Still the attacking lines, although much thinned and losing their regularity, rushed forward with grim determination. Then we on the cemetery lost sight of them as they were concealed from our eyes by the projecting spur of the ridge… Meanwhile a rebel force, consisting apparently of two or three brigades, supporting the main attack on its left, advanced against our position on Cemetery Hill.

We had about thirty pieces of artillery in our front. They were ordered to load with grape and canister, and to reserve their fire until the enemy should be within four or five hundred yards. Then the word to fire was given, and when, after a few rapid discharges, the guns ceased and… all we saw of the enemy was the backs of men hastily running away… Our skirmishers rushed forward, speeding the pace of fugitives and gathering in a multitude of prisoners… Then tremendous cheers arose along the Union lines…

The Union Soldiers held once again and pushed the Confederates back to their original position on Seminary Ridge. The Battle of Gettysburg was over.

The Aftermath

Lydia Leister returned to find her home severely damaged by artillery fire, and seventeen dead horses had been left in her yard, several of which had been burned around her best peach tree. Two tons of hay was gone from the barn, her wheat had been trampled, her spring spoiled, and all her fences burned. In 1865 she told a reporter that all she received in compensation for the damage was the proceeds from the sale of the bones of the dead horses, at fifty cents per hundred pounds.

Image: Leister Farm After the Battle

Image: Leister Farm After the Battle

This photo was taken from the middle of Taneytown Road facing north. The extensive damage to the stone and rail fences along the road and the white fences surrounding the house is plainly visible.

leister-farm5

Leister vowed to return the farm to its former condition. She did so well in rebuilding the farm that she was able to purchase 7 more acres in 1868, and in 1874, she built a large two story addition to her small home. In 1888, at age 79, she sold the property to the Gettysburg Memorial Association for $3,000. The farm was leased by tenants until 1933 when the National Park Service assumed responsibility for the property.

The widow Leister purchased a lot on the Emmitsburg Road and had the 1874 two story addition of her old home moved to that lot. Soon after she had built another addition to the house and lived there until her death in 1893.

SOURCES

Lydia Leister House

Battle of Gettysburg Council of War

Impact of War: The Slyder Family Farm

The Leister Farm: Meade’s Headquarters