Wife of Confederate General John Bell Hood

Anna Marie Hennen was born June 28, 1837. She was the daughter of a prominent New Orleans attorney, Duncan Hennen, and granddaughter of Alfred Hennen, Justice on the Louisiana Supreme Court. She was described as beautiful, charming, and she was educated in Paris, France. She would not meet John Bell Hood until after the Civil War.

Anna Marie Hennen was born June 28, 1837. She was the daughter of a prominent New Orleans attorney, Duncan Hennen, and granddaughter of Alfred Hennen, Justice on the Louisiana Supreme Court. She was described as beautiful, charming, and she was educated in Paris, France. She would not meet John Bell Hood until after the Civil War.

John Bell Hood was born June 29, 1831 in Owingsville, Kentucky. He and his siblings were left with their mother for approximately eight months each year during the middle and late 1840s while Dr. John Hood taught medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Young John Bell would be influenced by his grandfathers – Lucas Hood, a crusty veteran of the Indian Wars, and James French, a Revolutionary War veteran – who engendered his love for military life.

John Bell was urged by his father to take up the study of medicine, and was even offered an opportunity to study in Europe. But with the assistance of his uncle, Judge Richard French, he received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, enrolling on July 1, 1849.

Many cadets from southern states would struggle academically, due to the general lower quality primary education in rural areas. Hood’s weakest subjects were philosophy and French, and his strongest classes were mathematics and drawing. He ultimately graduated 44th out of 55 students in the Class of 1853, which included Civil War notables James B. McPherson, John M. Schofield, and Philip H. Sheridan.

In March, 1855, at the urging of U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, Congress authorized the formation of two new cavalry regiments that would protect settlements on the frontier of Texas. The Second Cavalry Regiment at Fort Mason, Texas, would be a virtual who’s who of the Civil War.

Its commander was Mexican War hero Colonel Albert Sydney Johnston; Robert E. Lee was the regiment’s lieutenant colonel; William J. Hardee and George Thomas, majors. Hood was promoted to second lieutenant of cavalry and reported to Colonel Johnston at Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, Missouri in October 1855.

Hood in the Civil War

In April 1861, with the outbreak of the Civil War, Hood resigned from the United States Army and offered his services to the newly formed Confederacy. He was promoted to full colonel, and given command of the Fourth Texas Regiment. On March 7, 1862, he was promoted to brigadier general and placed in command of the Texas Brigade of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. In October 1862, following the Battle of Antietam, Hood was promoted to major general at the recommendation of General Lee.

The men of the 1st Texas Regiment cheer their brigade commander during the Antietam Campaign of 1862.

On the afternoon of July 2, 1863, at the Battle of Gettysburg, General Hood’s division was ordered by General James Longstreet to begin the attack on the Federal defenses on Little Round Top. The Confederates would have to approach the Federals over several hundred yards of open ground and through rough, boulder-strewn ravines.

Brigadier General Evander Law sent scouts around the right side of Little Round Top, and found the rear approaches to the Union positions to be unguarded. Law approached Hood, apprising him of the situation, and Hood agreed wholeheartedly that a flanking maneuver would be more effective, and sent an urgent message to General Longstreet requesting permission to do so. Longstreet refused; Hood appealed to him again via courier. After Longstreet refused again, Hood sent his adjutant to implore him to reconsider. Longstreet again denied his request, and ordered him to continue the attack as previously instructed. At this point, Hood personally rode to Longstreet, who for the fourth time refused to allow him to attempt a flanking movement.

Hood began the attack up the Emmitsburg Road as directed. Twenty minutes after the attack began, Hood’s left arm was shredded by shrapnel from Federal artillery. He was taken to the rear, unable to participate any further in the battle. Although his wounded arm would be saved from amputation, it would be permanently paralyzed, and he carried it in a sling for the rest of his life.

The determined Confederate assault on the slopes of Little Round Top was eventually repulsed by the defending Federals; the carnage that Hood had anticipated did in fact materialize. His division succeeded in removing the Federal troops at the base of Little Round Top, but were able to seize only a portion of the summit of Little Round Top.

For the remainder of the battle, Hood’s division held their ground, while on July 3, 1863, Lee’s famous assault on the Union center, Pickett’s Charge, failed to defeat Meade’s Federals. The Battle of Gettysburg ended in a Confederate defeat, as Lee’s army began their retreat back to Virginia in a driving rain on July 4th.

During his convalescence, Hood was a hero to the people of Richmond. Confederate authorities sent Longstreet’s corps to northern Georgia to assist General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee in halting the Union advance through Middle Tennessee. Hood, recovering from his wound, accompanied the division into Georgia.

To the Western Theater

On September 18, 1863, Longstreet’s corps reached the banks of Chickamauga Creek. The next day, while leading a furious assault during the Battle of Chickamauga, Hood was struck in the upper right leg by a rifle ball, shattering the femur. He was carried to a nearby house with his bloody leg dangling off the side of the litter. Doctors amputated his right leg just below the hip. In less than seven weeks, Hood lost the use of one arm and underwent the amputation of his leg.

Hood was horribly disfigured by the amputation, retaining but a four-and-a-half-inch stump, but his great physical strength and will pulled him through the hideous ordeal. Outfitted with a wooden leg, Hood returned to the army. The injuries entitled him to a medical discharge, but he remained in the army and received a promotion to lieutenant general on February 1, 1864.

Hood was assigned to serve as a corps commander under General Joseph E. Johnston. Arriving in Dalton, Georgia, on February 4, 1864, Hood served under Johnston throughout Union General William T. Sherman‘s north Georgia campaign during the spring of 1864. On July 17, 1864, Hood received a temporary promotion to full general.

Throughout the summer of 1864, General Joseph E. Johnston, commander of the Army of Tennessee, had conducted a campaign to slow the advance of General William T. Sherman’s march to Atlanta. Disgusted with Johnston’s inability to stop Sherman’s progress, President Jefferson Davis replaced Johnston with Hood.

When Hood assumed command of the Army of Tennessee, he had more than 50,000 soldiers. By November, battle casualties had reduced the number to less than 30,000. Despite a reputation for bravery, Hood’s poor understanding of military tactics resulted in a series of crushing defeats to the armies under his command at the end of the Civil War.

On November 19, 1864, Hood’s army left Florence, Alabama, for an ill-fated invasion of Tennessee. On November 30, they suffered staggering losses in a decisive defeat at Franklin, Tennessee, at the hands of a Union force commanded by his West Point classmate General John Schofield.

Two weeks later, Hood was routed at Nashville on December 16 by his former U.S. Army colleague General George Thomas. After a humiliating retreat to Tupelo, Mississippi, Hood resigned his command on January 23, 1865.

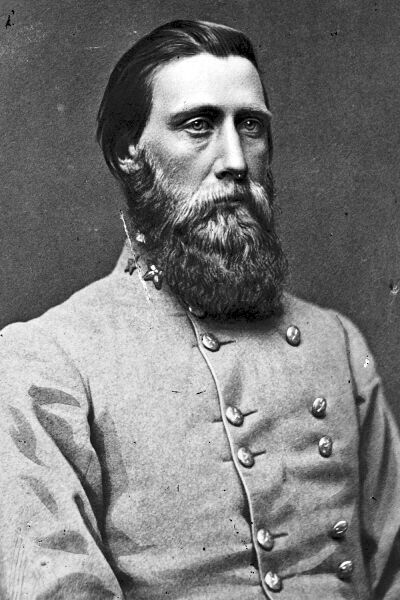

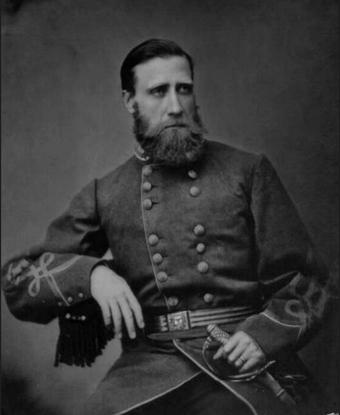

Image: General John Bell Hood

Image: General John Bell Hood

During the waning days of the Confederacy, Davis ordered Hood to travel to Texas and attempt to raise an army of 25,000 troops. Learning of the surrender of General Kirby Smith in Texas, Hood surrendered to Federal authorities in Natchez, Mississippi on May 31, 1865.

After receiving his parole, Hood went to New Orleans, Louisiana. He had borrowed $10,000 from friends in Kentucky, and would begin his new life there. New Orleans became home to many ex-Confederate generals. Among them were, James Longstreet, P.G.T. Beauregard, Jubal Early, Simon Buckner and Joseph Wheeler.

With business associates John C. Barwelli and Fred N. Taylor, Hood established J. B. Hood and Company, Cotton Factors and Commission Merchants, in February 1866. The business initially struggled and at the invitation of Longstreet, Hood took over the operation of his former commander’s insurance business.

Marriage and Family

In 1866, he met and fell in love with Anna Marie Hennen, a native of New Orleans. On April 30, 1868, with Simon Buckner as his best man, John Bell Hood married Anna Marie Hennen. This was his first marriage; he was 35.

To the surprise of many friends, John and Anna Hood began producing children at an alarming rate – eleven children in ten years, including three sets of twins. Their first daughter Lydia was born in 1869, twins Annabel and Ethel (1870), John Bell, Jr. (1871), Duncan (1873), twins Marion and Lillian (1874), twins Odile and Ida (1876) Oswald (1878) and Anna (1879). The eight girls and three boys were often referred to as Hood’s Brigade.

During the period between 1870 and 1879, it appeared Hood prospered in the insurance and cotton businesses and various other enterprises. He also assisted in fund raising for orphans, widows and wounded soldiers.

Hood purchased and resided in a spacious house in the upscale Garden District with his wife, their children and her recently widowed mother. The elegant home still stands at the corner of Camp and Third Street.

Love and Loss

During the summer of 1878, a yellow fever epidemic ravaged New Orleans, and resulted in the deaths of more than 3000 people. Spending the dangerous months at the Hennen family retreat near Hammond, Louisiana, the Hoods were spared the terror of the epidemic.

But New Orleans was virtually isolated, and the Cotton Exchange had closed. All but two insurance companies in the city went bankrupt. During the winter of 1878 and the spring of 1879, Hood was wiped out financially. He was forced to allow his personal insurance policies to lapse, and he mortgaged his house to its fullest value.

Yellow fever continued to threaten New Orleans during the summer of 1879, but finances would not allow the Hood family to move out of the city. On August 20, a case of yellow fever developed in the house directly across the street from the Hood home. The next day, one month after the birth of their eleventh child, Hood’s beloved wife Anna was stricken with the fever.

Anna Marie Hennen Hood died on Sunday, August 24, 1879, at 6:25 pm.

Walter V. Crouch, a close family friend, described the scene after Anna’s death in an August 31 letter:

I never saw a man so completely crushed in my life… He said that he was completely ruined and now without his wife he had nothing to live for. The precious little lambs who had gone to bed Sunday night knowing nothing of their mother’s death, began to come in one by one until nine came in and such a scene I never want to witness again.

After the children left he said, “Major, I have never had the fever, but if I should have it and it’s God’s will l’m ready to go. I have requested Colonel Flowers to take charge of my children, and to appeal to the Confederate soldiers to support them for I have nothing on earth to leave them.”

Completely devastated by the loss of his wife, struggling physically from his crippling war wounds, and under the stress of financial ruin and its impact on the security of his eleven young children, Hood contracted yellow fever on Thursday, August 27. His eldest daughter, ten-year-old Lydia, fell victim on the same day and died on August 29th.

Hood was soon advised of his own impending demise. Calmly accepting his fate, he agreed to receive last rites, and a priest at Trinity Episcopal Church was summoned to his house. Over the next twelve hours, Hood drifted in and out of consciousness.

At 3:30 am Sunday, August 31, 1879, General John Bell Hood died at age 48.

New Orleans, Louisiana

A brief funeral was held the next day, attended only by a few close friends. A salute was fired by a hastily arranged honor guard named the Continental Guards, and Hood’s body was laid to rest beside those of his wife and daughter in Lafayette Cemetery. A few years later, their remains were moved to the Hennen family crypt at Metairie Cemetery in New Orleans.

Within a week, the ten surviving Hood children, all under ten years of age, had been left destitute. As per Hood’s request, the Hood Orphan Memorial Publication Fund was set up by former Confederate general, P.G.T. Beauregard, for the purpose of raising funds for the children by selling Hood’s memoirs. Members of the Texas Brigade sold a family portrait.

Beauregard also organized a campaign to find homes for all the children. They were ultimately adopted by seven different families in Louisiana, New York, Mississippi, Georgia and Kentucky. A charity fund raised over $30,000 for the support and education of the orphans.

A braver man, a purer patriot, a more gallant soldier never breathed than General Hood.

~ Louise Wigfall Wright

SOURCES

John Bell Hood

General John Bell Hood

Wikipedia: John Bell Hood

In Defense of John Bell Hood

Biography of General John Bell Hood, CSA

General John Bell Hood: Myths and Realities

John Bell Hood &The Army of Northern Virginia

John Bell Hood Historical Society Newsletter Summer 2007