Hotly Contested Area on the Gettysburg Battlefield

Image: Bliss Farm

Image: Bliss Farm

Markers in the distance honor the men who fought here and deliniate the site of the William Bliss Farm that once existed here. Mid-left, in front of the trees, honors the 14th Connecticut Infantry. The clump of earth behind it is the remains of the earthen ramp that once led into the Bliss Barn. To the right is the 12th New Jersey Infantry marker. On the far right, out of frame, a smaller marker stands where the Bliss farmhouse once was. These markers are the only physical testaments to the struggle that took place over this key location.

Credit: Battle of Gettysburg Buff

Bliss Farm

After losing three of their five children to the cold of Chautauqua County, New York, William and Adeline Bliss traveled south in search of a warmer climate. In 1857, they purchased this sixty-acre farm just southwest of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The farm lay in a broad valley of gently rolling fields on the west side of Emmitsburg Road and across from Cemetery Ridge.

But this lovely spot was destined to be overrun by both armies as it lay in the path of General James Longstreet‘s assault on July 2 and General George Pickett‘s Charge on July 3.

The Blisses were in their early sixties at the time of the battle, and their two surviving daughters, Frances and Sara, were living with them. The family must have witnessed the arrival of General John Buford‘s Division on June 30 and General John Reynolds’ Corps on the morning of July 1. Apparently something happened at about twelve p.m. on July 1 that unnerved the Bliss family so much that they fled, leaving their noon meal on the table and the doors to their home open. Confederate skirmishers had occupied the Bliss farmhouse and barn by that evening.

Bliss Farm, July 2

By sunrise on July 2, 1863, the armies had laid out their battle lines, leaving the William Bliss Farm in a no man’s land between Union forces on Cemetery Ridge and Confederate troops on Seminary Ridge. The farmhouse and barn stood on a small ridge of high ground between the opposing armies. More than 11,000 men of the Union II Corps under General Winfield Scott Hancock climbed the slopes of the ridge below the town cemetery. Hancock reinforced his position with five batteries and placed infantry divisions of General John Gibbon and John C. Caldwell along the north-south ridge.

Shortly after ten a.m., General Alexander Hays ordered the 39th New York to reinforce the skirmishers in his front. Crossing the fence line along Emmitsburg Road, the 269-man unit occupied the fields north of the Bliss buildings. From his vantage point on Cemetery Ridge, Hays saw that a Confederate detachment had moved into the orchard west of the Bliss barn, and the New Yorkers were in trouble. Hays rode out to the faltering skirmish line – about 600 yards away – shouting instructions and encouragement. The 39th New York then maintained their position for about four hours in the intense gunfire and July heat.

The Bliss buildings were the only substantial shelter in the open fields below the town of Gettysburg, and they were rapidly becoming the center of the action. As the sharpshooting intensified, Confederate marksmen entered through the large doors and quickly filled the upper story of the Bliss barn. General Hays sent three companies of the 126th New York shortly after noon to clear out the snipers’ nest. They succeeded in capturing the barn and a few Southern sharpshooters.

CSA General Robert E. Lee was watching these developments from his command post at the Lutheran Seminary. Lee was planning to extend his line to the south to prepare for a flank march by General James Longstreet’s First Corps later in the day. Fresh troops from General A.P. Hill‘s Third Corps would extend the Rebel flank down Seminary Ridge. Longstreet’s men, marching south and out of sight behind the ridge, would then execute a surprise attack on the very end of the Union line.

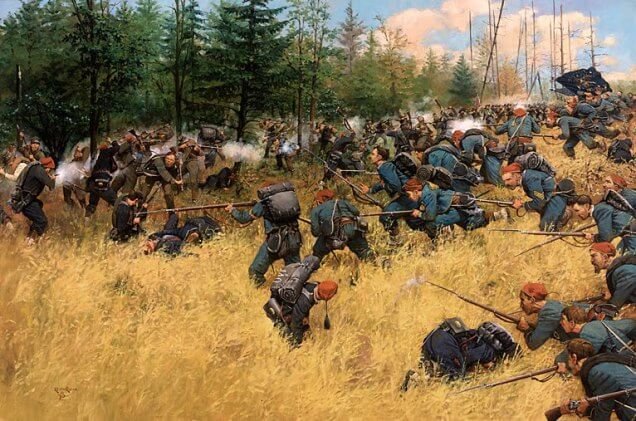

12th New Jersey Infantry at Bliss Farm

By midafternoon, the temperature had risen to more than 80 degrees, and the sun bore down on the combatants. Several Mississippi regiments under CSA General Carnot Posey now faced the Bliss property. Posey advanced his skirmishers to a fence line about 250 yards from the farm buildings. USA General Daniel Sickles had disobeyed orders and moved his III Corps to the high ground on Emmitsburg Road a mile south of the Bliss property, leaving the Union flank flapping in the breeze.

As the combatants closed in on each other, fighting intensified all along the line. As shot and shell flew over their heads, General Hays sent about 300 skirmishers to hold the Bliss property. But CSA Posey’s men had other ideas. As the 12th New Jersey Infantry advanced through the Bliss yard to a worm fence beyond the barn, the Southerners began picking off pockets of blue skirmishers remaining at the farm, once again making it rough going for the Union men. Headquartered nearby at the Bryan house, Hays and his staff also attracted the attention of the Mississippi riflemen.

Image: 12th New Jersey Monument

Image: 12th New Jersey Monument

Hancock Avenue on Cemetery Ridge

Sculptors: Beattie & Brooks

Credit: Stone Sentinels

At five p.m., General Hays ordered Colonel Thomas Smyth to seize the Bliss buildings and re-establish the Union skirmish line at the farm. He chose four companies of the 12th New Jersey Infantry to retake the farm and oust enemy sharpshooters. Posey’s riflemen and the Southern batteries on Seminary Ridge immediately opened fire on the charging Federal line. When they reached the farmyard, the New Jersey men fired a round into the barn and surrounded the building, capturing about 50 Mississippi soldiers. But Posey’s men continued firing from the Bliss house.

Image: Bas Relief Carving (bottom of monument above)

Image: Bas Relief Carving (bottom of monument above)

Bas relief carving on front plaque depicts the regiment’s assault on Bliss Barn. The 12th New Jersey arrived early on July 2, and one of their companies was soon sent to the skirmish line, but full combat had not started yet.

Credit: Civil War Librarian

Back on Cemetery Ridge, Hays ordered Smyth to “have the men in the barn take that damned white house and hold it at all hazards.” Within minutes, one of the New Jersey companies charged from the barn, capturing the white house and more of Posey’s men. Just then, everybody heard the CSA Third Corps marching up the valley, and the assault General Lee had planned that morning was well underway and rolling north toward Cemetery Ridge.

At six p.m., a strong line of Confederate skirmishers were flanking the New Jersey companies. To the south, skirmishers from the 2nd Georgia were pushing back the Union line, clearing the way for the advance. At approximately 6:30 p.m., 1,400 Georgians under CSA General Ambrose Wright were ready to begin their drive across the valley, in preparation for Longstreet’s attack. The four New Jersey companies holding the Bliss buildings a few hundred yards away were in a hot place, and they withdrew to Cemetery Ridge with their captives. The seesaw battle for possession of Bliss Farm, a demonstration of the tenacity of the combatants on both sides, was temporarily on hold.

Bliss Farm, July 3

12th New Jersey Infantry

The next morning dawned clear and bright, and Confederate marksmen soon informed the Union batteries on Cemetery Ridge that Bliss Farm was again in their control. At 7:30 a.m., Colonel Smyth sent the remaining five companies of the 12th New Jersey to clean out the snipers’ nest again. As they filed down the Bryan farm lane to the Emmitsburg Road, they crested the small rise halfway to the buildings, and Rebel fire killed three and wounded several others.

When they reached the Bliss buildings, the New Jersey troops charged into the barn and found all but three of the Confederates gone. Learning from their problems of the previous day, the Southerners had escaped down the bank in the rear of the barn, took cover in the orchard beyond and resumed firing. With pressure mounting from their front and flank, as well as artillery fire overhead, the New Jersey companies withdrew from the buildings and gathered their casualties as they fell back toward Cemetery Ridge.

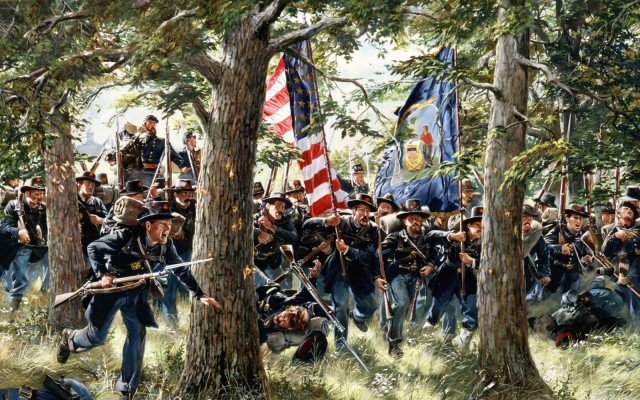

14th Connecticut Infantry

Undaunted by the failure of previous attempts, General Alexander Hays sent four companies – about 60 men – of the 14th Connecticut, ordering them to occupy the Bliss buildings “to stay.” The 14th had been decimated by hard fighting at Antietam, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. The regiment had not been replenished with fresh recruits since it was organized in August 1862, leaving only 160 men to report for duty at Gettysburg.

As they filed down the slope toward Bliss Farm, the detachment began to move out in formation, when they heard Hays’ voice from the ridge behind them, telling them to “scatter and run.” After crossing the Emmitsburg Road, the Connecticut companies went in opposite directions as they sprinted across the fields, but they soon drew fire from Confederate marksmen. Several fell dead.

When they reached the barn, the New Englanders discovered that the Confederates had moved into the farmhouse and orchard, where they resumed firing. The Connecticut men were trapped in the barn by gunfire from three sides and unable to defend themselves when Major Theodore Ellis led the remaining four companies of the 14th Connecticut across the Emmitsburg Road. As they joined the fray, they were met by deadly flank fire.

On their way to the farmhouse, the Northerners traded shots with the Rebels, who were once again running for the orchard beyond the barn. The Connecticut men entered the house by the double front doors and discovered that it offered little shelter. With “bullets piercing the thin siding and windows,” some of the men took their chances outside or ran for the barn. Confederate artillery pounded the Bliss buildings from Seminary Ridge, only 500 yards away.

Image: 14th Connecticut Monument

Image: 14th Connecticut Monument

Sculptor: John Flaherty

North Hancock Avenue

Inscription on front tablet:

The 14th C.V. reached the vicinity of Gettysburg at evening July 1st, 1863, and held this position July 2nd, 3rd and 4th. The regt. took part in the repulse of Longstreet’s grand charge on the 3rd [Pickett’s Charge], capturing in their immediate front more than 200 prisoners and five battle flags. They also, on the 3rd, captured from the enemy’s sharp-shooters the Bliss buildings in their far front, and held them until ordered to burn them. Men in action 160, killed and wounded 62.

The 14th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry is honored with several monuments on the battlefield. This, the most prominent one, marks the position from which the 14th helped repel Pickett’s Charge on the third day of battle.

Credit: CT Monuments

It was barely mid-morning on July 3, and the Bliss buildings had already changed hands three times. As the last companies of the 14th Connecticut left Cemetery Ridge, a lieutenant asked Colonel Smyth: “If … the Rebs make it so hot we can’t hold [the house and barn], shall we fire them?” Smyth replied, “We don’t know the word can’t!” On second thought, the colonel added, “If they make it too hot for you, burn the buildings and return to the line.” Unfortunately, that lieutenant was shot in the leg as the company crossed the fields, and he lay helpless as the detachment sped on.

In just over 24 hours, the struggle to control the no man’s land at Bliss Farm had involved more than ten Union and Confederate regiments, and it had changed hands many times. Recognizing that his men were in a desperate situation, General Hays sent Sergeant Charles Hitchcock with orders to burn the buildings. Carrying cartridge papers and matches, Hitchcock made his way across the fields to the barn and relayed the message. This excerpt from Pickett’s Charge, Eyewitness Accounts at the Battle of Gettysburg tells what happened next:

The order received, preparations were instantly made for firing the buildings. Wisps of hay and straw were soon on fire and by numerous hands applied at different places in the barn, and in the house a straw bed was emptied on the floor and the match applied. Then the men, taking up tenderly their wounded and dead and gathering their arms, started on their perilous return. … When they reached the Emmitsburg Road, they turned and saw how well they had done their work of destruction, the flames then bursting fiercely out of the house and barn.

When veterans of the 14th Connecticut Infantry returned to Gettysburg July 3, 1884 to dedicate a monument on Hancock Avenue, Chaplain Henry Stevens said in his address:

We believe [the fight for the Bliss buildings] to have been the most notable episode connected with the doings of any individual regiment occurring during the great battle of Gettysburg. … Had the buildings been destroyed the first time captured by our troops, many lives uselessly sacrificed would have been spared and much needless suffering avoided. It was one of the fool things of war. Yet it was a grand lesson to our boys, and it furnished one of the brightest points of their most glowing record. … and every man that escaped [un]hurt came back panting and wearied and feeling that out of the jaws of death he had come.

Today the Bliss Farm site at Gettysburg National Military Park is rarely visited, understandably. The barn and house were never rebuilt and there is nothing left to see – except a lovely meadow sprinkled with a few small monuments that delineate the farm buildings. But if you stand very still and listen very carefully, you can hear the echoes of those hot early days in July 1863 when it sounded like the world was coming to an end at Bliss Farm.

When the Bliss family returned to their farm after the Battle of Gettysburg, there was virtually nothing left of their former lives. After filing claims with the U.S. government for $2,500 to $3,500 in damages, they received no compensation, but they did not seem to mind much.

William and Adeline Bliss sold the remnants of their farm to Nicholas Codori in 1865 for $1,000. According to legend William said:

Let it go. I would give twenty farms for such a victory.

SOURCES

Stone Sentinels: Bliss Farm

Battle of Gettysburg: Fury at Bliss Farm

Wikipedia: 12th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry

CT Monuments: 14th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, Gettysburg