Wife of Union General Andrew Atkinson Humphreys

Andrew Atkinson Humphreys was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on November 2, 1810, to a family prominent in naval architecture. Humphreys was descended from the distinguished naval architects who designed Old Ironsides, the USS Constitution, and her five sister frigates during the War of 1812, Constellation and many other ships of the Old Navy. Humphreys was born to privilege. As a teenager, he was wild and uncontrollable; he played truant and ran away from his tutors.

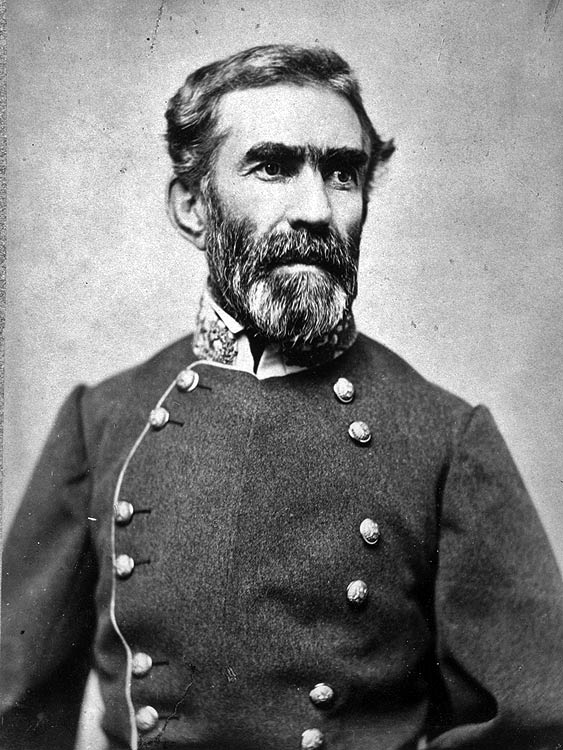

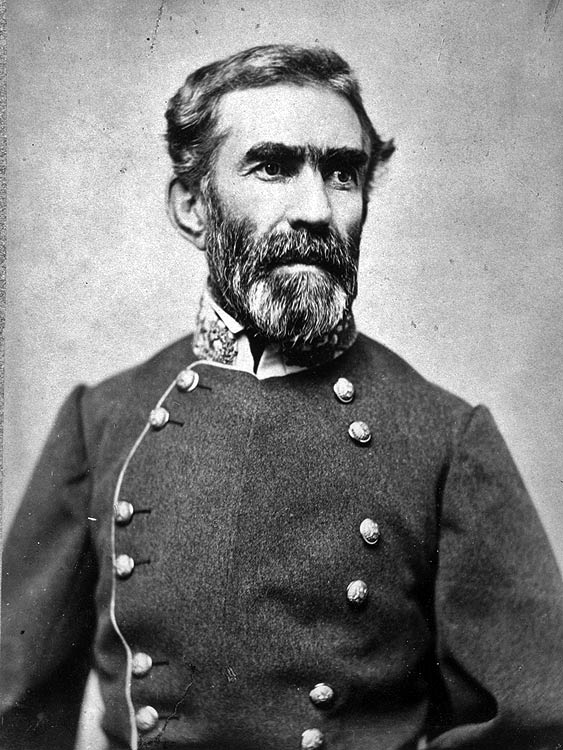

General Andrew Humphreys

In an effort to steer his son in a stable direction, his father secured the sixteen-year-old Andrew a place at West Point in 1827. Young Humphreys wasn’t ready for discipline. He earned demerits for not obeying the rules and ended up graduating 13th in a class of 33.

Humphreys’ early career in the military was equally undistinguished. He was assigned to a post in Provincetown, Massachusetts – at that time a remote fishing village of 1500 people – where he found his duties boring. Wanting to return to his studies, he wrote, “my labor [is] a dull, uninteresting task, and I go to it with disgust.”

After serving chiefly in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, and taking an active part in the Florida Seminole War, Humphreys health failed, and he resigned his commission on September 30, 1836.

In 1839, Andrew Atkinson Humphreys married Rebecca Hollingsworth.

Over the next 20 years, Humphreys’ career began to flourish. He made important contributions to a series of engineering projects in Chicago and Washington, DC, and in September 1850, Congress appropriated funds for a survey of the lower Mississippi River to discover what caused the river to flood and why sandbars were continually forming at the mouth of the river, blockading the port of New Orleans for months on end.

It was an important assignment, one that would influence the future development of the entire Mississippi Valley, and Humphreys desperately wanted it. He got the job, but it wasn’t what he expected. The Secretary of War, under congressional pressure, decided to split the appropriation between two men.

Humphreys would write a report for the Army Corps of Engineers. At the same time, a prominent civilian engineer, Charles Ellet Jr., would conduct his own independent investigation. Humphreys was furious. “I shall be crippled in my operations by this division of the appropriation,” he wrote a colleague. By splitting the task, Congress created an intense rivalry.

Ellet got to work right away; he collected very little data and completed a report within a year that was based largely on intuition. Humphreys, on the other hand, mounted a huge investigation composed of three teams that together collected a mountain of data.

In 1851, Humphreys was directed by the Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, to head the Pacific Railroad Survey Office, which oversaw the surveying of potential railroad routes from the East to California.

It was several years before Humphreys returned to the Mississippi project, and several more years passed before he completed his report. Humphreys felt he needed to write a masterpiece, one that would determine once and for all the superiority of Army engineers over their civilian counterparts. The 500-page document he finally produced was one of the most influential engineering reports ever written. Humphreys’ solution to flooding was the construction of levees along the river, and he recommended dredging at the mouth of the Mississippi to solve the problem of sandbars.

Humphreys in the Civil War

Andrew Humphreys was promoted to major on August 6, 1861, and became chief topographical engineer in Major General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. Initially involved in planning the defenses of Washington, DC, he shipped out with McClellan for the Peninsula Campaign in March 1862. He was promoted to Brigadier General of volunteers on April 28, 1862. On September 12, 1862, Humphreys assumed command of the new 3rd Division in the V Corps, leading the division in a reserve role in the Battle of Antietam.

A. A. Humphreys Monument

Erected by the State of Pennsylvania, this monument is the central feature in the Fredericksburg National Cemetery in Virginia.

In December 1862, at the Battle of Fredericksburg, Humphreys’ first real military engagement, was one of the Union’s most ill-conceived and poorly executed battles. Confederate troops under General Robert E. Lee were positioned on high ground behind a stone wall. The Union troops under new commander, General Ambrose Burnside, were ordered to charge at them. Column after column of men were mowed down under Confederate fire or driven back.

Humphreys’ division achieved the farthest advance against fierce Confederate fire from Marye’s Heights. His corps commander, General Daniel Butterfield, wrote: “I hardly know how to express my appreciation of the soldierly qualities, the gallantry, and energy displayed by my division commanders, Generals George Sykes, Humphreys, and Charles Griffin.” George G. Meade wrote: “He [Humphreys] behaved with distinguished gallantry at Fredericksburg.”

Lt. Cavada of the general’s staff recalled that just before he took his troops up to the Stone Wall at Fredericksburg, Humphreys had bowed to his staff in his courtly way, “and in the blandest manner remarked, ‘Young gentlemen, I intend to lead this assault; I presume, of course, you will wish to ride with me?'” Since it was put like that, the staff had done so, and five of the seven officers were knocked off their horses. When it was Humphreys’ turn, he charged up the hill on his horse in front of his men.

He and his division won fame for their valor, known for getting closest to the Stone Wall of any Union division before being driven back. Within ten or fifteen minutes, by his own account, Humphreys had lost 1000 men, a fifth of his command, but that didn’t seem to disturb him. Nor did the deaths of thousands more of his troops in subsequent battles. In his letters home, Humphreys never mentioned those losses. What concerned him was establishing his reputation as a military leader.

“He behaved with distinguished gallantry at Fredericksburg,” new Fifth Corps commander Major General George Meade wrote afterward. Meade sympathized with Humphreys – even after such a performance, Meade said, Humphreys was omitted from a long list for promotion “including such names as. . . Sickles . . . who have really done nothing,” probably as a result of Humphreys’s long association with the discredited McClellan.

In a letter to his wife, he described the thrill of battle:

As the storm of bullets whistled around me, and as the shells and shrapnel burst close to me in every direction with hissing sound, the excitement grew more glorious still. Oh, it was sublime! It is acknowledged throughout this army that no officer ever did as much with troops of short term of service as I did.

After the Battle of Chancellorsville, many of his men, whose terms of service had expired, were too tired or disgusted to re-enlist. Nearly a division in all evaporated from the Fifth Corps. On May 23, 1863, Humphreys was transferred to the command of the 2nd Division in the III Corps under Major General Daniel Sickles. Humphreys was the only West Point-trained career soldier in his new corps.

In mid-1863, Humphreys was developing into a fine field officer. Meade considered him a “splendid man,” and when Meade became commander of the Army of the Potomac three days before Gettysburg, he asked Humphreys to be his chief of staff. Humphreys refused, not wanting to give up combat duty for a desk job.

Humphreys at Gettysburg

Moving toward Gettysburg from Emmitsburg on the afternoon of July 1, Humphreys’ division arrived after dark, followed a guide along the wrong road, and almost blundered straight into a swarm of Confederates at Black Horse Tavern, miles to the west of the nearest friendly troops. Humphreys discovered his peril, tiptoed his division away from the near-meeting and, about midnight, found his place with the other Third Corps units camped on the southern end of Cemetery Ridge.

As General Humphreys led his division onto the Gettysburg battlefield on July 2, 1863, he was not well liked by his men. He was new to his division, and his men knew him only as a strict disciplinarian, exacting and precise, an unfeeling, bow-legged tyrant. They considered him an old man at the age of fifty-three, despite his relatively youthful appearance. His nickname was “Old Goggle Eyes” because of his eyeglasses.

Charles A. Dana, the Assistant Secretary of War, called him a man of “distinguished and brilliant profanity.” But Dana also found Humphreys to be charming, a man completely without vanity in a profession swarming with prima donnas. Theodore Lyman of Meade’s staff, who served under Humphreys later in the war, described him as a nice old gentleman who was boyish, with quick peppery ways, and extremely neat, “continually washing himself and putting on paper dickeys.”

At Gettysburg, at mid-afternoon on July 2, General Sickles moved his corps forward from its assigned defensive position on Cemetery Ridge, contrary to orders from General Meade. By Sickles’ order, Humphreys’ division moved forward to an exposed position, stretched out in a line running generally north and south along the Emmitsburg Road, facing west. Humphreys’ left abutted the men of Major General David Birney’s other Third Corps division at the Peach Orchard. His right was in the air (unprotected), a half-mile in front of the Second Corps supports on Cemetery Ridge.

When the Confederate attack came soon afterward, it started on the far Union left against Birney’s men, and to Humphreys’ dismay, his reserve brigade was drawn away to the south to help Birney. This left Humphreys with only two brigades when the Confederate attack reached his front.

Humphreys later wrote:

Had my Division been left intact, I would have driven the enemy back, but this ruinous habit (it doesn’t deserve the name of system) of putting troops in position, and then drawing off its reserves and second line to help others, who if similarly disposed would need no such help, is disgusting.

CSA General Lafayette McLaws‘ division converged on Humphreys’s short line from the left, front, and right. Sickles was by now down – wounded and unable to lead – and Birney ordered Humphreys to form a new line to the rear. Despite the difficulty of retreating and re-deploying while under attack by superior numbers, Humphreys managed to execute Birney’s order, according to subordinates, by placing himself “at the most exposed positions in the extreme front, giving personal attention to all the movements of the Division” with “conspicuous courage and remarkable coolness.”

At one point, Humphrey’s horse, already wounded six times, was hit by a shell, sprang in the air and threw the general violently to the ground. Humphreys mounted an aide’s horse and continued. Keeping the ranks steady by riding up and down and drawing his men back slowly with iron discipline, he managed to withdraw his division all the way to Cemetery Ridge, leaving 1500 men dead or wounded on the half-mile of ground over which he had made his retreat.

He put up the best fight that could have been expected, but Humphreys’ two brigades were demolished. They stayed on Cemetery Ridge that night, and were moved to the rear at sunrise the next morning. His division was finished as a fighting force; they spent July 3 in reserve behind the ridge.

Reward for Humphreys’ heroic performance on July 2 was immediate; he was promoted to major general on July 8, 1863. He finally agreed to General George Meade’s request to serve as his chief of staff; he did not have much of a division left to command. He served in that position through the Bristoe and Mine Run campaigns that fall, and the Overland Campaign and the Siege of Petersburg in Virginia in 1864.

When General Winfield Scott Hancock’s Gettysburg wound finally forced him from the field in November 1864, General Grant named Humphreys to command the II Corps, which he led for the rest of the siege and during the pursuit of General Robert E. Lee to the surrender at Appomattox Court House.

On March 13, 1865, Humphreys was promoted to brigadier general in the regular army for “gallant and meritorious service at the battle of Gettysburg,” and then to major general for the Battle of Sayler’s Creek during Lee’s retreat.

Chief of the Army Corps of Engineers

Humphreys’ uncompromising attitude served him well for most of his life, but not when he butted heads with his most obstinate and determined adversary: civilian engineer James Buchanan Eads. Eads was a self-made man. What he knew about engineering he’d taught himself. What he knew about the Mississippi River, he’d learned from years of backbreaking salvage work along a thousand of miles of the waterway.

In 1866, Humphreys was appointed Chief of the Army Corps of Engineers. He was finally in a position to influence federal spending on navigation projects and to implement some of the suggestions outlined in his Mississippi River report. This effort, however, would throw him into a bitter and angry conflict with Eads. The two men already disliked each other intensely. Their first fight had been about Eads’ bridge in St. Louis.

In 1873, in support of steamboat owners who claimed the bridge posed an obstacle to navigation, Humphreys insisted Eads build a canal around the bridge. Eads was outraged and looked to President Ulysses S. Grant for support. Grant sided with Eads and the canal was never built. Humphreys was left smarting from the encounter.

Meanwhile, Eads had already involved himself with the navigation problems at the mouth of the Mississippi. After years of dredging with little success, the Army Corps of Engineers, with Humphreys’ support, was pushing for the construction of a canal from below New Orleans to the Gulf of Mexico that would bypass the mouth of the river. Eads thought the idea was ludicrous.

Motivated in part by the conflict with Humphreys over the St. Louis Bridge, he suggested instead that lawmakers contract with him to build jetties, or underwater walls, at the point where the Mississippi meets the Gulf. Humphreys was enraged. As the author of the definitive report on the Mississippi, Humphreys felt Eads was encroaching on his territory.

The jetties would create a narrower channel that would speed up the water running between them. The faster water was made to flow, the more sediment it would carry. Eads claimed the extra force would be enough to carve out the sandbars and carry the sediment into the Gulf. Humphreys argued that his Mississippi River survey had proved jetties wouldn’t work. The jetties, he said, would simply move the sandbar out into the Gulf. The task of continually extending the jetties into the ocean, as the sand bar moved further out to sea, would never end.

If Humphreys was arrogant, Eads was moreso. The two men both waged intense lobbying efforts in Washington. In a letter to a business associate, Eads wrote: ” I have been engaged in a much bigger fight here than I at first expected, and for the last 30 days I think I have worked harder than ever before in my long lifetime of almost incessant toil.”

Eads not only won the contract; he also won the argument. After four years of construction, the jetties were completed in 1879. They created a channel thirty feet deep; one that ensured ships could get into and out of New Orleans. The port, once the ninth largest in the United States, became the second largest, after New York.

The defeat crushed Humphreys. It effectively undermined both the public respect he had commanded and the authority of the Army Corps of Engineers. But it turned out that Humphreys was right about one thing: the jetties did contribute to increased sand deposition at the mouth of the river. To overcome this, parallel jetties were built in 1884-86.

Disillusioned by this defeat and by congressional acts that limited the Corps’ authority, Humphreys resigned from his post on June 30, 1879.

General A. A. Humphreys

Gettysburg National Military Park

J. Otto Schweizer, Sculptor

A portrait of General Humphreys striding forward from the Division Line that extended along the Emmitsburg Road on July 2, 1863. His left hand rests on a sword that hangs on his left side. The sculpture rests on top of a rough granite base adorned with an inscription plaque on the front and the Pennsylvania state seal on the back. The monument is one of several that the Pennsylvania State Assembly appropriated money for on July 24, 1913. Dedicated July 1, 1919.

The Civil War veteran lived out the rest of his life in relative obscurity. In retirement, Humphreys studied philosophy, and was one of the incorporators of the National Academy of Sciences.

His published works were highlighted by his 1867 Report on the Physics and Hydraulics of the Mississippi River, which gave him considerable prominence in the scientific community.

He also wrote personal accounts of the war, published in 1883: From Gettysburg to the Rapidan and The Virginia Campaign of ’64 and ’65.

General Andrew Atkinson Humphreys died on the evening of December 27, 1883, at Washington, DC, and is buried there in the Congressional Cemetery.

I found no record of Rebecca Hollingsworth Humphreys‘ birth or death.

A. A. Humphreys

Andrew A. Humphreys

Brigadier General Andrew A. Humphreys

Andrew Atkinson Humphreys, 1810 — 1883

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Brigadier General Andrew Atkinson Humphreys