Wife of Union General Ambrose Burnside

Mary Richmond Bishop was described as somewhat religious, a rather tall, and a stately young woman, who conveyed a courtly presence. She was the daughter of Nathaniel and Fanny Windsor Bishop of Bristol, Rhode Island. Her father was a Rhode Island Militia Major.

Mary Richmond Bishop was described as somewhat religious, a rather tall, and a stately young woman, who conveyed a courtly presence. She was the daughter of Nathaniel and Fanny Windsor Bishop of Bristol, Rhode Island. Her father was a Rhode Island Militia Major.

Ambrose Everett Burnside was born in Liberty, Indiana on May 23, 1824, the son of a South Carolina slaveowner who had freed his slaves and moved his family to Indiana. At the age of 19, Burnside, through his father’s political connections was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He graduated in 1847, ranked 18 out of 38 in his class, and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Artillery.

He was appointed to an artillery unit in the Mexican-American War. He arrived too late to see any action, but continued to serve with the Artillery in the newly acquired territories in the Southwestern United States. Official Army documents record that Burnside was wounded by an arrow in his neck during a skirmish against Apaches in Las Vegas, New Mexico, but saw no other action under fire.

In 1852, Burnside was appointed to the command of Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island. He met Miss Mary Bishop one evening at a Militia Ball held at the Old Armory in Providence, during his first visit to that city. But Burnside was soon ordered to return to the far western frontier to serve again in the Apache Wars, which interrupted their romance, but he soon returned to Rhode Island.

Ambrose Burnside married Mary Richmond Bishop on April 27, 1852. Although Mary dearly loved children and favored two nieces in the Burnside family, Ambrose and Mary had no children of their own.

While serving on the plains, Burnside became dissatisfied with the standard army carbine. In November 1852, Burnside resigned his commission in the US Army, but kept a position in the state militia. He took up permanent residence in Rhode Island, and devoted his time and energy to designing and patenting a breech-loading rifle that bears his name, the Burnside Carbine. The carbine used a special brass cartridge, also invented by Burnside.

With a working model, Burnside established his first company, Burnside & Bishop, which was destroyed by fire in late 1853. With the insurance money, he then formed the Bristol Firearms Company in January 1854 in Bristol, Rhode Island. Mary’s family invested heavily in his venture, and Burnside was able to acquire the services of a respected Massachusetts gunsmith, George P. Foster, during the infancy stage of his corporate development.

In August, 1857, a board of army officers reported favorably on the Burnside breechloader. The Secretary of War under President James Buchanan, John B. Floyd, contracted with the Bristol Firearms Company to equip a large portion of the Army with his carbine, and induced Burnside to establish a factory for its manufacture, which was established as the Bristol Rifle Works.

The works were no sooner complete than another gun maker allegedly bribed Floyd to break his $100,000 contract with Burnside. At that same time, Burnside ran as a Democrat for one of the Congressional seats in Rhode Island in 1858, and was defeated in a landslide. The burdens of the campaign contributed to his financial ruin. During the Civil War, the Burnside Carbine came into its own. More than 55,000 rifles were produced for the US Army from 1857 to 1865, and it was the third most used carbine utilized by the Union cavalry.

Burnside was forced into bankruptcy and had to hand over his rights in the company to his creditors. He pledged all of his personal property to the liquidation of his debts, and by practicing strict economy, Burnside eventually paid every obligation. He got a job in Chicago under future Union General George B. McClellan, then vice-president of the Illinois Central Railroad, where Burnside became treasurer. Burnside’s connection with the Illinois Central continued for the rest of his life. After the war he was one of many ex-Generals to be appointed to the boards of railway companies.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Burnside was a Brigadier General in the Rhode Island Militia. He raised a regiment, the First Rhode Island, and was appointed its Colonel on May 2, 1861. Within a month, he ascended to brigade command in the Department of Northeast Virginia. He inexpertly commanded the brigade at the Battle of First Bull Run, and was promoted to Brigadier General in the Union Army.

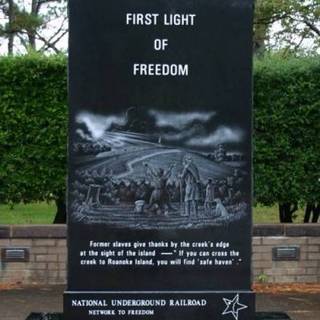

Burnside began to work on a plan to seize parts of the southern coastline that would involve a force 12,000 to 15,000 strong, recruited from coastal areas of New England. This force would descend on lightly defended parts of the coast, seize strategically located places, and gain control of the coastal waters of the Confederacy. McClellan approved of the plan, with Burnside commanding the new North Carolina Expeditionary Corps – three brigades assembled at Annapolis, MD – and the Department of North Carolina from September 1861 until July 1862.

By the start of 1862, Burnside was ready to move. He conducted a successful amphibious campaign that closed over 80% of the North Carolina seacoast to Confederate shipping for the remainder of the war. For his successes at the battles of Roanoke Island, New Bern, Beaufort, and Fort Macon – the first significant Union victories in the Eastern Theater – Burnside was promoted to major general on March 18, 1862.

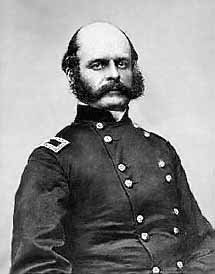

Image: Major General Ambrose Burnside

Burnside was a tall and handsome man of soldierly bearing, with charming manners, which won for him many friends and admirers.

Following McClellan’s failure in the Peninsula Campaign, March through August 1862, Burnside was offered command of the Army of the Potomac. Refusing this opportunity, in part due to his loyalty to McClellan, he detached part of his corps in support of Major General John Pope’s Army of Virginia in the Northern Virginia Campaign. Again offered command following the debacle at Second Bull Run, he again declined. Confident in his ability to command smaller armies, Burnside was not so confident that he could carry the burden of commanding the main army of the Union.

Burnside was given command of the Right Wing of the Army of the Potomac (the I and IX Corps) during the Maryland Campaign. He fought at South Mountain and then at the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, where his two corps were placed on opposite ends of the Union battle line. He nonetheless remained in wing command over the IX Corps — a cumbersome arrangement that may explain his slowness in attacking and crossing what is now called Burnside Bridge. The delay allowed Confederate Lt. General A. P. Hill’s Confederate division to come up from Harpers Ferry and repulse the Union breakthrough.

McClellan was removed after failing to pursue General Robert E. Lee’s retreat from Antietam, and despite his relatively poor performance at Antietam, when Lincoln returned to his search for a new commander for the Army of the Potomac, it was Burnside he turned to. Although he still felt that he wasn’t capable of performing the job, Burnside reluctantly accepted the role, possibly because the most likely alternative was General Hooker, whom Burnside considered even less suited for high command. On November 10, 1862, General Ambrose Burnside replaced General McClellan in command of the Army of the Potomac.

President Abraham Lincoln pressured Burnside to take aggressive action and on November 14, 1862, approved his plan to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. Burnside’s plan was sound. He would march the Army of the Potomac to Fredericksburg, cross the river on pontoon boats before Lee’s widely separated Confederate forces could unite to stop him, and attempt to capture Richmond. When the army reached Fredericksburg on November 17, there were very few Confederates on the opposite bank. There were also no pontoon boats. By the time they arrived, so had the Confederates.

On December 13, 1862, Burnside launched a frontal assault on strong Confederate defenses on the hills above Fredericksburg, and was repulsed with heavy losses. The Battle of Fredericksburg was a humiliating and costly defeat for the Union. His lack of resolution led to his losing the battle, in addition to disappointing Lincoln and injuring the army’s morale. Accepting full blame for the loss, Burnside offered to retire from the army, but this was refused.

In January 1863, in an attempt to make up for Fredericksburg, General Burnside decided to cross the Rappahannock River and attack the Confederates from behind. As the troops began moving, it began raining heavily, with strong winds. By the end of the day, the march across the river was a muddy, disorganized mess, which was later called Burnside’s Mud March. In its wake, he asked that several officers be relieved of duty and court-martialed, and he also offered to resign. Lincoln accepted his resignation, and on January 26, replaced him with General Joseph Hooker.

But President Lincoln was unwilling to lose Burnside completely. Unlike many failed generals, Burnside made it clear that he didn’t consider himself suited to command at the highest level. In March 1863, Lincoln sent Burnside to Kentucky as commander of the Department of the Ohio, with orders to move into East Tennessee, where the population was strongly pro-Union. His advance was to be timed to coincide with Union General William Rosecrans’ attack on Chattanooga, further to the south. After lengthy delays in front of Chattanooga, General Rosecrans finally made his move in August 1863.

In the Knoxville Campaign, Burnside’s expedition progressed well. He captured Knoxville, the main city in East Tennessee, on September 2. One week later he captured the main Confederate army in East Tennessee at Cumberland Gap. Believing that he had achieved what he had been appointed to do, Burnside once again attempted to resign, but his resignation was refused.

After General Rosecrans was defeated at the Battle of Chickamauga, Burnside’s command was in serious danger of attack. In the middle of November, that danger was realized when a major expedition under Confederate General James Longstreet was detached from the siege of Chattanooga with orders to recapture Knoxville and East Tennessee. Burnside skillfully outmaneuvered Longstreet and was able to reach his entrenchments and safety in Knoxville, where he was besieged, but Longstreet withdrew, eventually returning to Virginia.

Burnside was rewarded for his skilful performance at Knoxville with command of the IX Corps. After a period of reorganization in Maryland, that corps joined General Grant for the Overland Campaign. They fought at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, and Bethesda Church, where Burnside performed in a mediocre manner, appearing reluctant to commit his troops to frontal assaults after his Fredericksburg experience. After Cold Harbor, Burnside took his place in the siege lines at Petersburg, Virginia, in July 1864.

Trench Warfare at Petersburg

At Petersburg, Burnside agreed to a plan suggested by a regiment of Pennsylvania coal miners in his corps: to dig a mine under a fort in the Confederate entrenchments and ignite explosives there to achieve a surprise breakthrough. Only hours before the infantry attack, General George Meade decided it was too dangerous for Burnside to use his division of black troops, who had been specially trained for this mission.

Burnside could not decide who to send in their place, so he had his three subordinate commanders draw lots. The division chosen by chance was that commanded by Brigadier General James H. Ledlie – Burnside’s worst division. Instead of going around the huge crater created by the blast, Ledlie’s men marched into it, became trapped, and were subjected to murderous fire from Confederates around the rim, resulting in high casualties. Ledlie was reported to be drunk, and well behind the lines during the battle.

General George Meade blamed Burnside for the fiasco at the Crater, and Burnside was relieved of command on August 14 and placed on leave. A court of inquiry was convened in August, finally ending on September 9, after seventeen days. The court criticized Burnside for ‘failure to comply with orders and to apply military principles,’ but was satisfied that Burnside believed that he had taken the correct actions before the attack. Four other officers were also criticized. Even Grant was (indirectly) criticized, for failure to appoint a single officer to command all troops taking part in the operation.

In December 1864, Burnside met with President Lincoln and General Ulysses S. Grant about his future. He was contemplating resignation, but Lincoln and Grant requested that he remain in the Army. He was never recalled to duty, and finally resigned his commission on April 15, 1865.

After the war, Ambrose Burnside had successful business and political careers, serving as a director of the Illinois Central Railroad, and as president of several other railroad companies, including the Cincinnati & Martinsville Railroad, the Indianapolis & Vincennes Railroad, and the Rhode Locomotive Works.

Burnside was elected to three one-year terms as Governor of Rhode Island from 1866–1868. He was President of the Veterans’ Association of the Grand Army of the Republic. The National Rifle Association chose him as their first president at its inception in 1871.

He was also elected to two six-year terms as US Senator from Rhode Island in 1870 and 1876, which post he held until his death. During his tenure, he served as chairman of Senate Education and Labor Committee, and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Mary Richmond Bishop Burnside died in 1876.

Major General Ambrose Burnside died very suddenly on September 13, 1881, from neuralgia of the heart at his home in Bristol, R.I. During the funeral ceremonies, he was remembered for his valuable service as a soldier and as a statesman, and in his adopted state he was the most conspicuous man of his time. He and Mary are buried side by side at Swan Point Cemetery at Providence.

General Burnside Statue

Burnside Park, Providence, RI

Some historians believe that General Burnside has been treated unfairly, not only during his lifetime but throughout written history as well. The traditional view is that he was a poor commander. Those who are inclined to be more charitable toward him ascribe his failures to politics, insubordination, a lack of adequate communication in the field, or at times, just plain bad luck.

Burnside is commonly referred to as Rhode Island’s Own in recognition of his years of loyal service to his adopted state. Another of General Burnside’s legacies is the term sideburns, which originated from his bushy side-whiskers, joining his ears to his mustache, but with a clean-shaven chin.

SOURCES

Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside

Ambrose Burnside 1824 – 1881

Wikipedia: Ambrose Burnside

Major General Ambrose E. Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside Biography

Ambrose Everett Burnside 1824 – 1881

Grave of General Ambrose Everett Burnside

Honestly this isn’t much of an article on Mary. It is about her husband. Yes, there may not be much known about her but….

It’s kinda sad about how little information in this is about her. I came on this website for information on her, but instead I got all about Ambrose.