Wife of Confederate General Lafayette McLaws

Emily Allison Taylor was born in Kentucky in 1824, the “pretty, witty, lively, sweet, and sincere” daughter of John and Elizabeth Lee Taylor. Emily was the niece of President Zachary Taylor, and cousin of future Confederates Richard Taylor and Jefferson Davis.

Emily Allison Taylor was born in Kentucky in 1824, the “pretty, witty, lively, sweet, and sincere” daughter of John and Elizabeth Lee Taylor. Emily was the niece of President Zachary Taylor, and cousin of future Confederates Richard Taylor and Jefferson Davis.

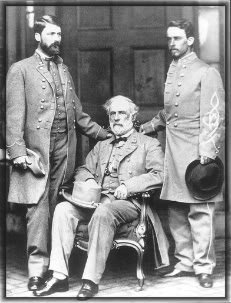

Image: General Lafayette McLaws

Lafayette McLaws was born on January 15, 1821, in Augusta, Georgia, but had ties to South Carolina through his mother. He first met future Confederate General James Longstreet at school in Augusta. McLaws spent a year at the University of Virginia before receiving his appointment to West Point. He graduated in 1842, ranking 48th out of 56 cadets; Longstreet was 40th.

Having served in the Indian Territory, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida prior to the Mexican War, McLaws entered Texas with Zachary Taylor’s army, then transferred to that of Winfield Scott, but spent a large portion of the war on sick leave.

McLaws, who pronounced his first name “La-FAY-ette,” met Emily Allison Taylor while stationed at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri.

He served for some time in Indian territory, and in 1846, he joined General Zachary Taylor’s army of occupation at Corpus Christi, Texas, and was engaged in the defence of Fort Brown, the battle of Monterey, and the siege of Vera Cruz during the Mexican-American War. His health failing, McLaws returned to the United States on recruiting duty, and after the peace was assistant adjutant-general in the Department of New Mexico for two years.

McLaws married Emily Taylor on August 9, 1849, at Lexington, Kentucky. He was able to spend only four days with his new bride before leaving on his next military assignment in the Department of New Mexico. Lafayette and Emily McLaws raised seven children.

Lafayette McLaws was a feeling, literate man who poured out his experiences in candid, often sentimental letters to his wife about his attitude toward life in general. Those he wrote during the war reveal what it was like to serve as a division commander in the Confederate Army in terms of staffing, living arrangements and day-to-day life, and about nepotism in the Army of Northern Virginia.

Emily McLaws had to move the family several times during the War, which prompted discussions about their inability to create a permanent home for their family. The letters McLaws wrote to his sons Willie and Johnnie illustrate the difficulty in raising children when the father is not home. McLaws asked about the boys’ kite flying and sent new grammar books home in the midst of his court-martial.

The Civil War

Lafayette McLaws had been serving as a captain of infantry for almost 10 years when Georgia voted to secede from the Union on January 19, 1861. By March, he had resigned his commission in the U.S. Army and returned to Georgia. In less than a month, he was a newly-commissioned major in the Confederate Army.

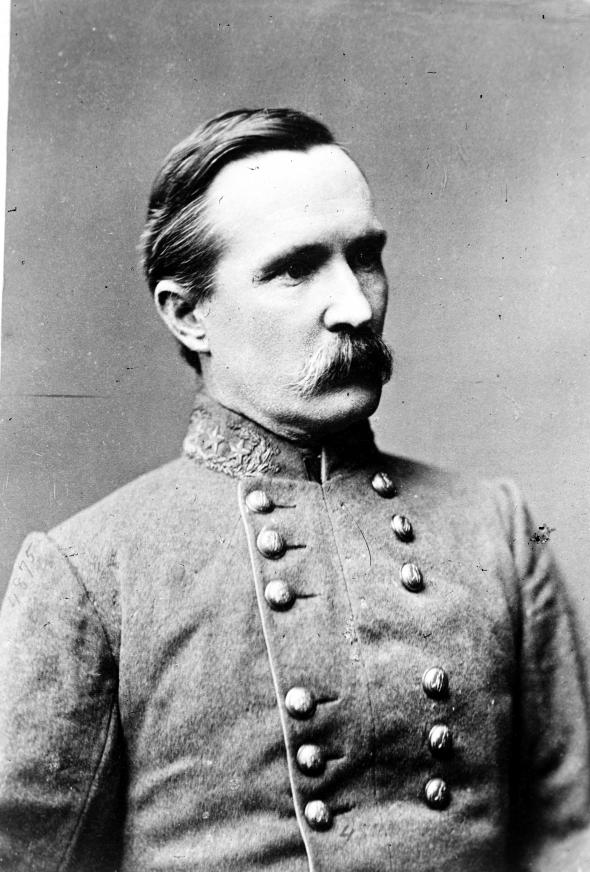

McLaws and his regiment soon moved north to Virginia, where they were assigned to the forces under the command of Brigadier General John Bankhead Magruder, who commanded the small Army of the Peninsula defending Richmond against USA General George B. McClellan in the early portion of the Union’s Peninsula Campaign in 1862. This separate army was incorporated as a division in the Army of Northern Virginia on April 12, 1862.

McLaws’ military experience gave him advantages over regimental commanders who had been civilians before the war, and he was commissioned as a Brigadier General on September 25, 1861. Soon after, Magruder was made a major general, and McLaws remained under his command until the spring of 1862. A creditable performance in the Battle of Williamsburg won McLaws a promotion to Major General in May 1862.

McLaws’ complexion was swarthy, his hair was curly and very black, his beard was enormous and bushy and half-covered his broad face, and his coal black eyes peered out in a rather owlish way. He was short, compact, and burly, with big square shoulders, deep chest, and large, muscular arms. Although he developed a suitable mastery of profanity, his martial demeanor hid a sensitive soul.

His reliability and dogged tenacity rubbed off on his division, however, and made them as hard to dislodge as any in the army. He exuded unflinching fortitude, with the downside being that he lacked military imagination, and was at his best when told exactly what to do and when closely supervised by superiors. A division commander early in the war, Lafayette McLaws proved capable, but not brilliant enough to warrant further advancement.

The 41 year old, stout, round-faced man joined Major General James Longstreet‘s First Corps in the Army of Northern Virginia as First Division commander and stayed with Longstreet for most of the war.

McLaws was summoned by General Robert E. Lee for the Maryland Campaign in September 1862. McLaws’ division was split from the rest of the corps, and they took part in the operations that resulted in General Stonewall Jackson‘s capture of Harper’s Ferry. The troops had been for sixty hours under fire and without water on Elk Ridge; McLaws halted for a few hours in Harper’s Ferry, and then marched for Sharpsburg.

At that time, General Lee was desperately hurrying to concentrate his army at Sharpsburg, and he expected McLaws to demand the last energies of his men. His division took forty-one hours to march from Harper’s Ferry to Sharpsburg, which A.P. Hill’s division covered in nine. McLaws arrived on the field as John Bell Hood‘s Texas Brigade was being driven back.

General Lee was disappointed in McLaws’ late arrival. In his report after Sharpsburg, Lee came as close to censure as he ever did in written comments about his officers’ performances when he wrote that “[McLaws’] progress was slow, and he did not reach the battlefield at Sharpsburg until sometime after the engagement of the 17th began.” This impaired his standing with General Lee.

At the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, McLaws’ was one of the divisions defending Marye’s Heights. The defensive preparations above the town were the type of work at which McLaws excelled. Under Longstreet’s supervision and with the help of corps engineers, McLaws’ men dug pits for their batteries and strengthened parts of their line with obstructions.

McLaws then went to work on a sunken road which made up part of his front, improving on a stone wall that protected the road by digging a ditch on the town side of the road, and banking the dirt against the wall. Within this ideal firing trench, he provided his men with stacks of loaded muskets, and they slaughtered the Union soldiers who bravely mounted waves of attacks on that impregnable position.

When the battle was over, the snowy ground in front of the trench was thickly carpeted with Union dead from many divisions; it was the most one-sided victory of the war. The reports of both Lee andLongstreet praised McLaws. The prevailing opinion was that McLaws was competent in a defensive fight, but lacked the imagination to function successfully on offense.

At the Battle of Chancellorsville, while the rest of Longstreet’s corps was detached for duty near Suffolk Virginia, McLaws performed well enough when under the direct command of General Lee. On the third day, McLaws received word in the latter stages of the battle that Lee wished his and General Jubal Early’s division to attack and overwhelm the isolated Union Sixth Corps that was marching toward the Confederate rear.

Called on for the initiative to solve the puzzle of how to move against the enemy, McLaws wasparalyzed by indecision; he had always been happier obeying a direct order than acting on a discretionary one. McLaws was the highest ranking major general in the Confederate army, and Jubal Early the most recently appointed, but McLaws ended up letting Early direct the whole operation. McLaws accomplish his mission, but Lee was disappointed that McLaws had not attacked more aggressively and caused more harm to the enemy, instead of letting him escape across the Rappahannock River.

The loss of General Stonewall Jackson at Chancellorsville catalyzed a reorganization of the Army of Northern Virginia that Lee had been contemplating for months. The two corps, Jackson’s and Longstreet’s, would become three, and two new corps commanders would be named. Longstreet recommended McLaws, and McLaws thought himself deserving of corps command by virtue of his seniority and his reliable service.

In late May, Lee chose Major Generals Richard Ewell and A.P. Hill for the new posts, and McLaws was crushed. Both of the men chosen were from Virginia, and McLaws felt that favoritism had deprived him of his rightful standing in the army. But there was more to it than that. His listless performance at Chancellorsville had disappointed Lee and recalled his similar failure before Sharpsburg the previous fall. Lee simply did not think McLaws’ performance over the last year indicated that he was deserving of further advancement. McLaws requested a transfer, but it was denied.

Despite his disappointment, McLaws’ strengths as a division commander were appreciated by his troops. He attended closely to the needs of his men and had their respect. “He was an officer of much experience and most careful,” noted Longstreet’s aide Moxley Sorrel. “Fond of detail, his command was in excellent condition, and his ground and position well examined and reconnoitered; not brilliant in field or quick in movement there or elsewhere, he could always be counted on and had secure the entire confidence of his officers and men.”

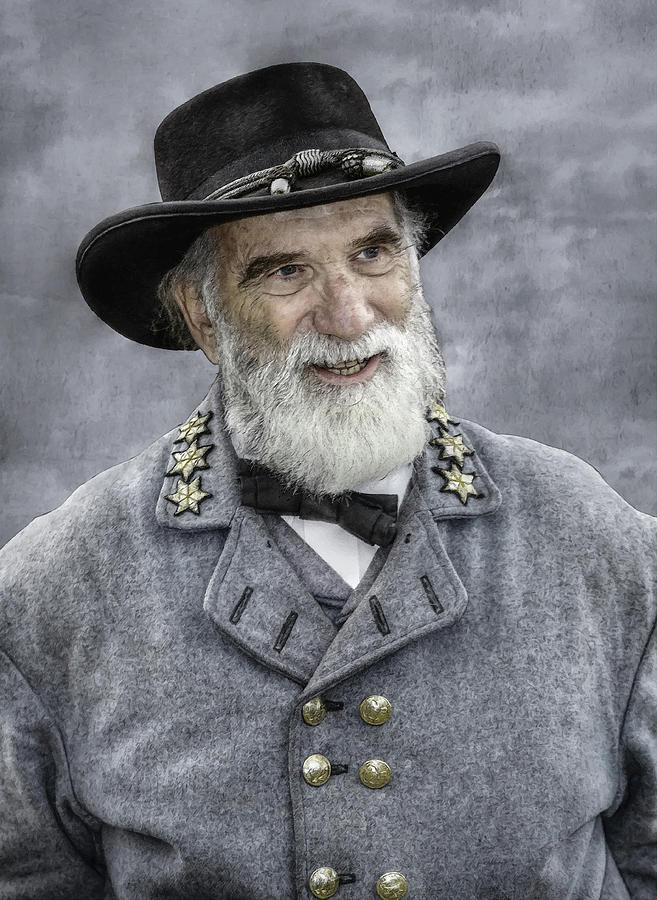

Image: Bust of General McLaws

Image: Bust of General McLaws

At the Georgia Confederate Memorial

Forsyth Park in Savannah, Georgia

McLaw’s division was in Greenwood, Pennsylvania, on July 1, 1863, with orders from Lee to march east over South Mountain to Gettysburg, about 17 miles away. The men, however, were prevented from using the only road over the mountain by Ewell’s trains, which clogged the road for ten hours. Falling in behind the trains, McLaws marched until midnight. His men camped at Marsh Creek, about 3 miles west of Gettysburg.

On the morning of July 2, McLaws rode up to General Lee’s headquarters and got personal instructions from Lee on how to place his division for the day’s attack. Lee wanted McLaws to place his division perpendicular to the Emmitsburg Road at the Peach Orchard and go northward toward the town, rolling up the Union left flank. McLaws went back to his men, who had moved forward that morning along the Chambersburg Pike. He marched them back to Herr Ridge and waited for Longstreet to give the signal for the trek to their destination.

Longstreet was in a peevish mood and stalled the march until noon. When the two-division-long column finally got moving to the south, it soon came to a stretch of road visible to enemy scouts on Little Round Top. To achieve surprise, the column would have to start over and find a hidden approach. McLaws still wanted to lead the march, however, so rather than everybody turning around and Hood’s division leading, McLaws marched back along the entire column to the Chambersburg Pike, wasting valuable time.

McLaws finally finished his troubled march around 3:30 pm, reaching the woods along Seminary Ridge opposite the Peach Orchard only to find that the Federal line extended past his front to the right, toward Little Round Top. News of the whereabouts of the Union left flank had obviously been faulty.

His assault as planned by Lee would meet head-on opposition.

Under a hastily improvised plan, McLaws would now have to wait for Hood, deploying on his right, to attack first. About 4:30 pm, the artillery opened up and Hood’s brigades plunged forward toward Little Round Top and Devil’s Den. Longstreet stayed with McLaws, so there was not much for McLaws to do except to move among his men, steadying them, and telling them to be patient.

Finally, around 5:30 pm, Longstreet gave the signal and Kershaw’s brigade moved out, and in a matter of minutes had stormed through Union lines in the Peach Orchard and beyond. As they poured forward, they outflanked the Union brigades in the Wheatfield and sent them back in a rout. McLaws waited behind with Longstreet while his four brigades stormed eastward.

When McLaws’ brigades had gone as far as they could go in the dying light of July 2, Longstreet ordered them back before they were annihilated by the Union reserves which continued to arrive in front of them. The men of the division pulled back to safe positions from Devil’s Den to the Peach Orchard for the night. McLaws’ division had fought with deadly ferocity, but casualties for the day were about 2,200, 30% of his force.

In his letters, McLaws was critical of Longstreet’s performance that day; he considered the attack unnecessary, and blamed Longstreet for not reconnoitering the ground and for continuing the attack after his errors were discovered. According to McLaws, Longstreet gave contrary orders, and behaved in an exceedingly overbearing manner.

On July 3, McLaws’s Division was pulled back to the west side of Emmitsburg Road after the failure of Pickett’s Charge. McLaws did not write a report after the Battle of Gettysburg, but later wrote that the attack was “unnecessary and the whole plan of battle a bad one.” Longstreet failed to commend McLaws in his report after the battle. McLaws never again served with the Army of Northern Virginia.

In November, 1863, McLaws accompanied Longstreet to Tennessee to come to the aid of General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. He arrived too late to take part of the fight at Chickamauga, but he did participate in the Chattanooga Campaign. Longstreet and his two divisions then set out to take Knoxville.

At the Siege of Knoxville, McLaws reluctantly carried out General Longstreet’s order to assault Fort Sanders, and halted the attack when he perceived that success was impossible. Longstreet blamed McLaws for the failure of the attack, and accused him of failure to execute orders and a general lack of cooperation.

On December 17, 1863, Longstreet relieved McLaws of command for the failure of the attack on the fort, citing “a want of confidence in the efforts and plans which the Commanding General has thought proper to adopt.” Many believe that Longstreet needed a scapegoat for a poorly executed campaign, but a military court found McLaws guilty on several charges and he was relieved of command.

In a letter to Confederate Adjutant and Inspector General Samuel Cooper on December 30, Longstreet submitted three charges of “neglect of duty” but did not request a court-martial because McLaws’ “services might be important to the Government in some other position.” (In that same letter, he requested a court-martial for Brigadier General Jerome B. Robertson, who had been charged with “incompetency” by his division commander.)

General McLaws also wrote to Cooper on December 30, disputing Longstreet’s charges and requesting a court-martial to clear his name. Cooper forwarded Longstreet’s letter to Secretary of War James Seddons and to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, with the annotation that Longstreet was not authorized to relieve and reassign officers under his command without a formal court-martial. Davis ordered the court-martial of both generals, although he opposed relieving McLaws until a successor could be appointed.

The court-martial of McLaws and Robertson convened in Morristown, Tennessee, on February 12, 1864, with Major General Simon Buckner serving as president of the court. The proceedings suffered delays as witnesses—including Longstreet—were not available to appear as scheduled, in some cases because Longstreet had granted them leaves of absence.

The court found McLaws guilty of some charges on May 4, 1864. Cooper’s office published the court’s findings on May 5, exonerating McLaws on the first two specifications of neglect of duty, but finding him guilty of the third — “failing in the details of his attack to make arrangements essential to his success.”

McLaws was sentenced to 60 days without rank or command, but Cooper overturned the verdict and the sentence, citing fatal flaws in the procedures of the court, ordering McLaws to return to duty. Jefferson Davis disapproved the findings on May 7, and also ordered him back to duty with his division, now back in Virginia.

McLaws was bitter about his fate, claiming that Longstreet had used him as a scapegoat for the failed Knoxville Campaign. Writing in his memoirs many years after the war, Longstreet expressed regret that he had filed charges against McLaws, which he described as happening “in an unguarded moment.” In time, the animosity healed between the two Confederate veterans, but McLaws never fully forgave Longstreet for his actions.

Only through President Davis’ intervention did McLaws obtain another commission. On May 18, 1864, McLaws was assigned by the War Department to the District of Georgia with headquarters at Savannah, where he spent most of 1864. When USA General William Tecumseh Sherman’s forces approached the city during his March to the Sea, McLaws and his army in the area had little choice but to flee.

McLaws retreated into South Carolina, eventually joining General Joseph E. Johnston and his Army of Tennessee. He commanded a division at the Battle of Averasboro, North Carolina, on March 16, 1865, and at Goldsboro on March 21. His letters contain interesting information about the Battles of Averasboro and Bentonville, the final battle of the war there.

McLaws was then sent to Augusta to resume command of the District of Georgia, but before he reached that place, General Lee had surrendered at Appomattox. McLaws surrendered his command with General Johnston’s army near Durham Station, North Carolina, on April 26, 1865. On October 18, 1865, General Lafayette McLaws was pardoned by the U.S. government.

After the war, McLaws returned to Georgia and worked in the insurance business and was active in veteran organizations. In 1876, President Ulysses S. Grant, McLaws’ old friend and former Mexican War comrade, appointed McLaws to the position of collector of the Internal Revenue Service in Savannah, and later postmaster of Savannah from 1876 until 1884.

Despite his wartime differences with Longstreet, McLaws initially defended Longstreet in the post-war attempts by Jubal Early and others to smear his reputation. Just before his death, however, he began speaking out about Longstreet’s failures at Gettysburg.

In November 1886, McLaws opened a series of lectures by Northern and Southern military leaders that was instituted by the Grand Army of the Republic in Boston, his subject being “The Maryland Campaign.”

The final years of Emily McLaws’ life in Savannah were perhaps the most difficult. Her daughter Virginia wrote:

After my father’s term expired [as the Savannah postmaster], he made their living in several ways. When it was impossible to get along without help, my mother took in boarders, which is never a pleasant job. There was no pension for a Confederate officer. We got along the best we could, each one doing his part.

Emily Allison Taylor McLaws died in May 1890 from typhoid one month later, and was buried in Savannah’s Laurel Grove Cemetery. Virginia concluded her mother’s sketch with, “My mother, Emily Taylor McLaws, was one of the finest, sweetest, and most capable women I ever knew, perfectly fearless and brave.”

General Lafayette McLaws died unexpectedly on July 24, 1897, at his Anderson Street home in Savannah. He is buried next to his wife of forty-one years in Laurel Grove Cemetery.

Laurel Grove Cemetery

Laurel Grove Cemetery

Savannah, Georgia

SOURCES

Lafayette McLaws

Our Georgia History

Georgia Historical Society

Wikipedia: Lafayette McLaws

The West Woods Trail – PDF File

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Major General Lafayette McLaws

Lafayette McLaws: Setting the Record Straight