Wife of Confederate General William Barksdale

William Barksdale was born on August 21, 1821, in Smyrna, Tennessee. He graduated from the University of Nashville and practiced law in Mississippi from the age of 21, but gave up his practice to become the editor of the Columbus [Mississippi] Democrat, a pro-slavery newspaper. He enlisted in the 2nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment and served in the Mexican-American War as a captain and quartermaster.

William Barksdale married Narcissa Saunders of Louisiana in 1849.

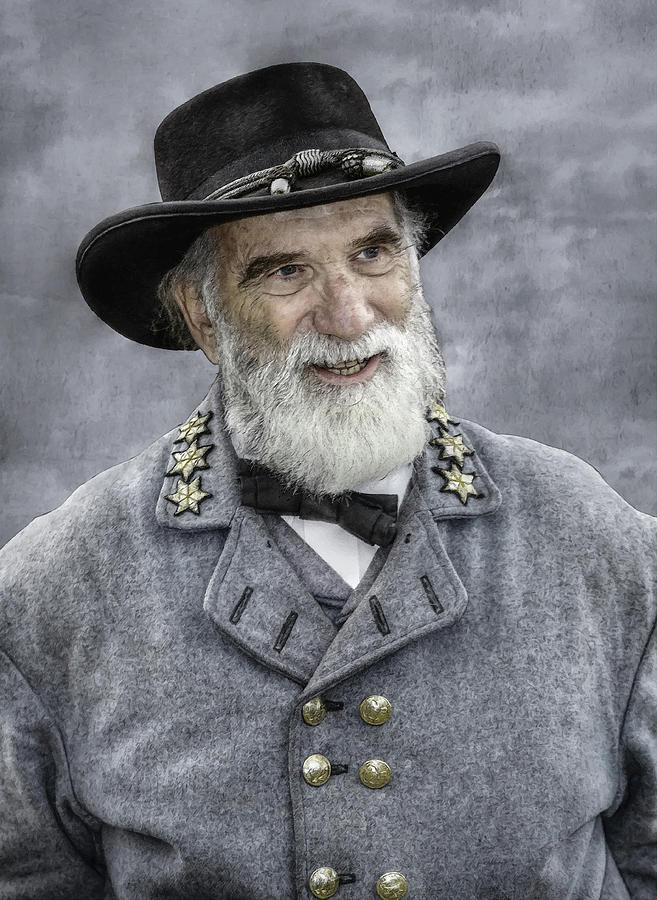

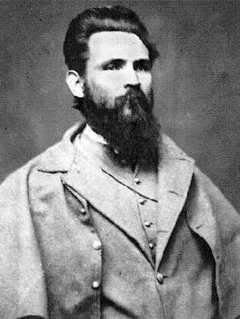

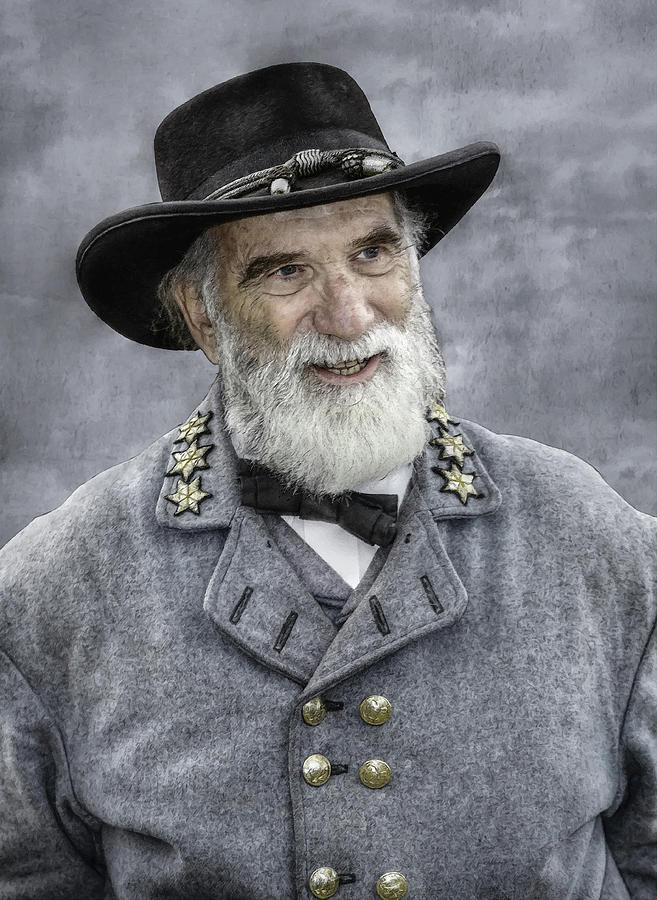

William Barksdale

In 1853, Bardsdale entered the U.S. House of Representatives and achieved national prominence as a States’ Rights Democrat, serving from March 4, 1853, to January 12, 1861. He was considered to be one of the most ferocious of all the “Fire-Eaters” in the House.

Barksdale in the Civil War

After the state of Mississippi seceded, Congressman Barksdale resigned his seat in the House to become adjutant general, and then quartermaster general, of the Mississippi Militia. In May 1861, he was appointed colonel the 13th Mississippi Infantry, a regiment that he led in the First Battle of Bull Run that summer. That fall, Colonel Barksdale got so drunk that his superior brought him up on charges. Barksdale escaped punishment by giving “a solemn pledge” not to touch a drop for the duration of the war.

In spring 1862, he took his regiment to the Virginia and fought in the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles. When his brigade commander, General Richard Griffith was mortally wounded at Savage Station on June 29, 1862, Barksdale assumed command of the brigade and led it in an heroic, but futile, charge at the Battle of Malvern Hill. The brigade became known as Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade.

General Robert E. Lee wrote about Barksdale’s performance: “Seizing the colors himself and advancing under a terrific fire of artillery and infantry, [he displayed] the highest qualities of the soldier.” Barksdale was promoted to brigadier general on August 12, 1862.

In the Maryland Campaign, Barksdale’s brigade was assigned to the division of Major General Lafayette McLaws in Lt. General James Longstreet’s First Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. It was one of the brigades that attacked Maryland Heights, leading to the surrender of the Union garrison at Harper’s Ferry. At the subsequent Battle of Antietam, McLaws’ Division defended the West Woods against the assault by USA General John Sedgwick’s division, saving the Confederate left flank.

At the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, Barksdale’s Brigade defended the waterfront of the town from Union forces attempting to cross the Rappahannock River, and repulsed Federal attempts to bridge the Rappahannock River by firing from cellars and rifle pits in the riverfront buildings of the town. Barksdale’s men clung to their position even after a concentrated Yankee artillery bombardment that pounded the buildings into rubble.

At the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, Barksdale’s brigade defended the heights above Fredericksburg, this time against his previous adversary, Sedgwick, whose VI Corps was over ten times the size of his brigade. When they were overrun by Sedgwick’s 23,000-strong Sixth Corps, Barksdale managed to evacuate his survivors, rally his brigade, and take back the lost ground the next day.

For the next several months, Barksdale’s Brigade stayed in the Charlottesville, Virginia, area. The unit’s next major engagement was during Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania. The Mississippi Brigade was then comprised of the 13th, 17th, 18th and 21st Mississippi Infantry, assigned to General Lafayette McLaws Division of General James Longstreet’s Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Barksdale at Getttysburg

At the Battle of Gettysburg, Barksdale’s Brigade arrived with McLaws’ Division after the first day of battle was finished. For the second day of the battle – July 2, 1863 – General Robert E. Lee’s plan was for General Longstreet’s Corps to march up the Emmitsburg Road and roll up the Union left flank.

At noon on July 2, Barksdale’s men began a march on a long, frustrating, back-and-forth route from Herr Ridge to a line facing east from Pitzer Woods, their jump-off position for the attack on the Union left flank. The brigade arrived in place at about 3:30 pm.

Barksdale could see through the trees that the Peach Orchard, immediately opposite his line, was bristling with Yankee infantry and artillery. Plans were changed, and all McLaws’ brigades waited for General John Bell Hood’s division to attack first, from the right.

Large and heavy, Barksdale did not present a pretty picture on a horse – when he rode he leaned forward as if trying to push his horse faster. He always led his brigade on horseback, with his hat off, and his wispy white hair flying.

At 5:30 pm, General James Longstreet gave the order for McLaws’ division to charge. Barksdale shouted, “Attention, Mississippians! Battalions, Forward!” and the 1600-man brigade burst from the woods at about 6:30 pm.

Thus began an assault that has been described as one of the most breathtaking spectacles of the Civil War. A Union colonel was quoted as saying, “It was the grandest charge that was ever made by mortal man.” Barksdale’s sector of the attack placed him directly at the tip of the salient in the Union line anchored at the Peach Orchard, and defended by the Union III Corps.

Barksdale’s tightly packed line surged forward, not stopping while the Union muskets and cannon tore at the line. It swept up and over the Federal front, and smashed through the thin Union line just west of the Sherfy house. The combatants swept around the bullet riddled house while wounded soldiers, seeking protection, crawled into the house, the barn or any other structure that offered any form of safety.

The Grandest Charge Ever Seen

Mort Kunstler, Artist

Barksdale’s Missippippians at Gettysburg, July 2, 1863

Barksdale, a huge, balding man with long white hair, leads the charge on a black horse, waving his hat and screaming orders through the din. The sunlight catches Barksdale and the flag, as well as the Sherfy barn in the left background. The men at the right are charging up the hill from the west out of a small apple orchard and near a worm fence in the foreground that ran across the field at that time.

Still the charge hurtled ahead. Some of the Mississippi regiments turned to the north and caused General Andrew A. Humphreys’ division to crumple and fall back to Cemetery Ridge. Other regiments went straight ahead. Barksdale kept urging his men on: “Brave Mississippians, one more charge and the day is ours!”

The Mississippi Brigade seemed unstoppable as they pushed through the Peach Orchard and into the valley toward Cemetery Ridge. The fields ahead were filled with confused, splintered Yankee regiments and retreating artillery, an inviting prize for the battle hardened men.

But the attack was slowed down by shredded, disordered lines and fatigue. The fiery Barksdale cursed and whipped his men forward across the Emmitsburg Road, north of the Peach Orchard where Union gunners and infantrymen were overrun and surrounded.

Barksdale’s men had gone about a mile, as far as Plum Run, when they met with a Union counterattack. New York regiments fought back furiously and temporarily blocked the center regiments of the Mississippi Brigade. The 73rd New York Infantry raced in to fill a sudden gap in the line and hit Barksdale’s soldiers head on.

Barksdale’s men were soon reinforced by two additional Southern brigades from General A.P. Hill’s Corps. The field between the road and Plum Run was soon covered with blue-clad bodies as Humphreys’ men stubbornly bought time with their lives. Yet they gave most of the Union artillery the precious time they needed to get away and reform on Cemetery Ridge.

While rushing towards a gap in the Federal line, the Confederates were met by deadly canister from a last ditch defense by the Federal artillery. The Southern troops were badly shaken and while trying to rally them, Barksdale was mortally wounded. It was reported that a federal officer had ordered his entire company to fire at the Confederate commander.

Barksdale was first hit by a bullet above the left knee but stayed in command. Next his left foot was hit by a cannonball and nearly taken off at the ankle. Then he was hit by another bullet in the left side of the chest, which knocked him off his horse. He told his aide, W.R. Boyd, “I am killed! Tell my wife and children that I died fighting at my post.”

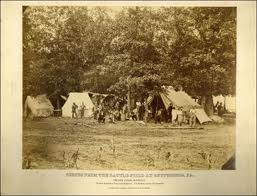

Without their leader, the disorganized and exhausted Southerners could not maintain their forward progress forward in the face of the charge of a fresh Union brigade. As they retreated, Barksdale’s troops were forced to leave him for dead on the field. General Barksdale was later taken on a litter to a Union field hospital at the Jacob Hummelbaugh farmhouse.

Major Robert H. Forster of the same regiment recalled this scene:

During the night of the 2nd as I approached the little house – now the field hospital – I stepped upon something that felt so peculiar that I stopped and picked it up. It proved to be an arm. Happening to look at the west window I saw an outline of a pyramid of some sort, which on examination I found was a pile of hands, arms, feet and legs which the surgeons had thrown out in their work and which had now reached the window sill.

In front of the house lay General Barksdale mortally wounded, his breast torn and one leg shattered… Alternately begging for water, which a drummer boy was giving him with a spoon, and cursing the Yankees, it was a most pathetic scene… He died during the night.

Jacob Hummelbaugh Farm

Union II Corps Field Hospital

Taneytown Road

Gettysburg, PA

General William Barksdale was buried in Jacob Hummelbaugh’s yard, until his wife traveled to Gettysburg after the war with her husband’s favorite hunting dog to retrieve his body. General Barksdale’s remains were re-buried at Greenwood Cemetery in Jackson, Mississippi.

The story goes that the general’s old dog refused to leave the gravesite even after the body was exhumed and loaded for transport home to Mississippi, and remained there at the gravesite even after repeated attempts the next day by Mrs. Barksdale to get the dog to return home with her and her husband’s remains. Finally, the animal had to be left behind.

For days afterward, the loyal dog refused to budge and turned down all offers of food and water from everyone, eventually dying on his master’s former grave. As the years passed, it was said that a howling dog could often be heard at the Hummelbaugh farm, and especially on the nights of July 2 and 3, the anniversary of General Barksdale’s wounding and death.

SOURCES

Pitzer Woods

The Peach Orchard

Wikipedia: William Barksdale

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. The Generals of Gettysburg: William Barksdale

The American Civil War: The Battle of Gettysburg