Wife of Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory

Angela Mallory (1815-1901) was best known as a devoted civic leader in the pioneer days of Florida before it was admitted to the Union (1904). The University of Florida at Gainesville officially admitted 500 women in 1947, and Angela Mallory Hall, one of the first dormitories for female students, was named in her honor. It was dedicated on February 17, 1950 and was the last remaining women-only hall until Fall 2004 when it became coed by floor.

Angela Mallory (1815-1901) was best known as a devoted civic leader in the pioneer days of Florida before it was admitted to the Union (1904). The University of Florida at Gainesville officially admitted 500 women in 1947, and Angela Mallory Hall, one of the first dormitories for female students, was named in her honor. It was dedicated on February 17, 1950 and was the last remaining women-only hall until Fall 2004 when it became coed by floor.

Angela Sylvania Moreno, daughter of a Spanish patriarch, was born in Pensacola, Florida, on June 20, 1815. Her father was a prominate leader in Pensacola and the surrounding area. Stephen Russell Mallory was born in Trinidad, British West Indies, sometime about the year 1813. His parents were Charles and Ellen Russell Mallory.

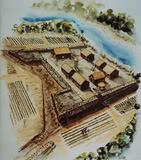

Mallory’s father was a construction engineer originally from Connecticut, who met and married the Irish-born Ellen Russell in Trinidad, and there the couple had two sons. The family moved to the United States and settled in Key West, Florida in 1820, when the island was inhabited by only a few fishermen and pirates.

His mother Ellen Russell Mallory (1792-1855) became known as the First Lady of Key West, where she was the first white female settler. She moved there with her ailing husband Charles and two young sons in 1823. Charles Mallory died of consumption in 1825, and her elder son John died shortly thereafter, at only fourteen years of age.

To support herself and her surviving son Stephen, Ellen opened her home as a boarding house for seamen. During frequent yellow fever outbreaks, she served as the town’s nurse. She provided a good education for her surviving son, Stephen, sending him to Nazareth Hall Military Academy, a Moravian school in Nazareth, Pennsylvania. Although he was for all of his life a practicing Catholic, he had only praise for the education he received at the academy.

After three years, his mother could no longer afford to pay his tuition, and in 1829, at the age of 16, Stephen returned home. Mallory held a few minor public offices. At the age of nineteen he was appointed by President Jackson inspector of the customs at Key West, for which he earned three dollars per day. He joined the Army and took part in the Seminole War (1835–1837). His mother Ellen was a leading figure in the growth and life of Key West until her death in 1855.

Young Mallory prepared for a profession by studying law in the office of Judge William Marvin. Key West was often sought as a port of refuge for ships caught in storms, and was for the same reason near frequent shipwrecks. Marvin was recognized as an authority on maritime law, particularly applied to laws of wreck and salvage, and Mallory argued many admiralty cases before him. He was reputed to be one of the best young trial lawyers in the state.

His career prospering, Mallory courted and married Angela Moreno on July 19, 1838. Their marriage produced nine children, five of whom died young; two daughters, Margaret and Ruby, and two sons, Stephen R. Jr. and Attila, survived into adulthood. During Stephen’s political career, Angela carried the burdens of parenting and domestic responsibilities alone.

Committee on Naval Affairs

After serving the State of Florida as probate judge and the United States as collector of customs at Key West, Mallory was elected to the United States Senate from Florida in 1851, and re-elected in 1857. He was placed on the Senate Committee on Naval Affairs.

The Mallory family moved from Key West to Pensacola, Florida in 1858.

Mallory’s tenure on the Committee on Naval Affairs came during a time of great innovation in naval warfare. He kept abreast of developments, and made sure that the U.S. Navy would incorporate the latest thinking into its new ships. In 1853, the committee recommended passage of a bill providing for the addition of six new screw frigates to the fleet; some considered them to be the best frigates in the world. In 1857, his committee persuaded the Senate to authorize twelve sloops-of-war. These entered the navy beginning in 1858, on the verge of the Civil War.

Another innovation that was being considered was that of armor. Mallory was somewhat ahead of his time, enthusiastically supporting iron cladding for ships before the fledgling metals industry in the country could supply it in the necessary quantities. No armored vessels were commissioned while he was in the Senate, but whatever fault there was lay elsewhere.

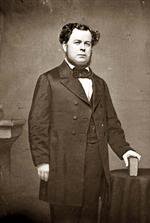

Confederate Secretary of the Navy

After Florida’s secession from the Union, Mallory resigned his Senate seat on January 21, 1861. Based on his past experience in updating the U.S. Navy, Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed Mallory Secretary of the Navy on March 4, 1861. He held that position throughout the existence of the Confederacy.

Mallory found himself at the head of a naval department on the eve of a great war, without a ship or any of the essentials of a navy. He had not only to organize and administer, but to build the ships and boats, provide their ordnance and machinery, and create a naval force in a country which possessed few resources.

After viewing the disparity between shipbuilding facilities of the Confederacy and those of the Union, he set forth a fourfold plan:

1. Send out commerce raiders to destroy the enemy’s mercantile marine.

2. Build ironclad vessels in Southern shipyards for defensive purposes.

3. Obtain by purchase or construction abroad armored ships capable of fighting on the open seas.

4. Employ new weapons and techniques of warfare.

Mallory purchased warships in Europe, refurbished captured Federal vessels, and, when possible, armed Southern-owned ships then in Confederate ports. Four of the Confederate Navy raiders were purchased in Britain: CSS Florida, Georgia, Shenandoah, and above all Alabama.

From the start, one of the main efforts of the Confederate Navy was to counter the blockade of its ports by the Union Navy. Mallory believed that by attacking the merchant ships that carried trade to Northern ports he could force Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles to divert his own small fleet to defend against the raiders.

Secretary Mallory was directly involved in the activities of commissioned raiders: ships that were sent out to destroy enemy commerce. He first proposed their use as early as April 18, 1861. The first raider, CSS Sumter, avoided the Union blockade at New Orleans on June 30, 1861. From then until the end of the war, the small group of raiders plundered Union shipping, inflicting damage on the American Merchant Marine. They failed, however, because Welles maintained the Union blockade, and international trade continued as before, carried in ships flying foreign flags.

Because few others in the Confederate government were interested in naval matters, Mallory had almost free rein to shape the Confederate Navy according to the principles he had learned while serving in the U.S. Senate. Some of his ideas, such as the incorporation of armor into warship construction, were quite successful and became standard in navies around the world; but the navy was often handicapped by the administrative ineptitude in the Navy Department.

The Ironclads

No other aspect of Mallory’s tenure as Confederate Secretary of the Navy is better known than his advocacy of armored vessels. He argued that the Confederacy could never produce enough ships to compete with the industrial Union on a ship-by-ship basis. As he saw it, the South should build a few ships that were individually so far superior to their opponents as to dominate. He hoped that armored warships would prove to be the ‘ultimate weapon.’

Under Mallory’s direction, the Confederacy built formidable ironclad vessels. The first was CSS Virginia. An armored casemate was built on her hull, and she carried 12 guns and was also fitted with an iron ram. On March 8, 1862, she attacked the Union fleet enforcing the blockade at Hampton Roads, Virginia, and sank two major Union warships, USS Cumberland and Congress. The damages she suffered were negligible.

In that first day, she had demonstrated the basic validity of Mallory’s belief that armored warships could destroy the best wooden ships and were almost impervious to damage in return. When Virginia returned to battle the next day intending to finish off Minnesota, she encountered the Union’s Monitor. The two armored vessels fought inconclusively, demonstrating the flaw in Mallory’s argument: an ultimate weapon is truly decisive only if one side does not have it.

After Virginia, most other Confederate ironclads had at best limited success, and many were complete failures. Particularly embarrassing were four that were contracted to be built for service on the Mississippi River. Of the four, only one entered into combat in the way that was intended, with full crew and under steam.

Mallory must bear a large part of the blame. Poor administration is among the foremost reasons for the delays that hindered completion of the vessels. Because he did not delegate responsibility, he was swamped with details of the construction of Virginia while letting problems concerning the other ships go unresolved. And the Navy had to work with only the materials and funds that were left over after the Army had satisfied its needs.

Of the others, Tennessee was destroyed on the stocks; Mississippi was hastily launched and then burned to avoid capture; and Louisiana was used merely as an ineffectual floating battery at the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, when the fate of New Orleans was decided, and she was then blown up rather than be surrendered.

Stephen Mallory

The loss of New Orleans came as a tremendous shock to the Confederacy, and a spate of recriminations followed. Members of Congress, noting the failure of the ironclads, blamed the navy in particular, and suggested that there was no need for a separate Navy Department. Hoping to forestall such a proposal, Mallory persuaded the Congress instead to investigate the conduct of the department.

A Congressional investigation into the Navy Department for its failure in defense of New Orleans ensued. Each house put five of its members on the investigating committee. After six months of taking testimony and deliberations, the committee concluded that it had no evidence of wrongdoing on Mallory’s part.

The investigation may have weakened Mallory politically and certainly diverted him from other duties, but it was not enough to drive him from office. Perhaps because there was no one to replace him and perhaps because he absorbed shafts that were aimed at the president, Davis retained him in the cabinet until the end of the war.

New Weapons

The Civil War provided a testing ground for numerous innovations in warfare, and Mallory encouraged the development of several other weapons. For example, he favored the use of rifled guns, as opposed to the smoothbore muzzle loaders used in the Union Navy. The Brooke rifle, designed by the head of the Office of Ordnance and Hydrography, gave Rebel gunners an advantage over their Yankee counterparts that persisted to the end of the war.

Mallory also organized the Confederate Torpedo Bureau, which built torpedoes, floating mines and the legendary torpedo boat H.L. Hunley. The first ship to be lost to mines was USS Cairo, on December 12, 1862. Subsequently, more vessels of all types were lost in combat to mines and torpedoes than from all other causes combined.

The Hunley later used a spar torpedo to sink USS Housatonic, the first ship to be sunk by a submarine. Spar torpedoes were also immediately adopted by the Union Navy, and one was used in October 1864 to sink the ironclad CSS Albemarle.

During the war, Mallory’s letters to Angela recounted battles, troop movements and everyday life during the Civil War. In particular he wrote a long detailed letter from the battlefield during the Seven Day’s Battles. In other letters, Mallory defended his decision to invest in ironclads.

After the surrender of General Robert E. Lee‘s army at Appomattox, Mallory remained with Jefferson Davis and the other cabinet members as they fled from Richmond to North Carolina, South Carolina and Washington, Georgia, where he submitted his resignation. Mallory then went to La Grange, Georgia, where he was reunited with Angela and their children.

A large part of the population of the Northern states believed that the Davis government was somehow involved in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, although there was no evidence of their involvement. Stephen Mallory was one of the Confederate leaders who were charged with treason.

On May 20, 1865, while he was still at La Grange, he was roused from his sleep at about midnight and taken into custody. From there he was taken to Fort Lafayette on a small island in New York Harbor, where he was confined as a political prisoner for ten months. However, and it became increasingly clear that no one in the Confederate government was guilty of assassinating the former president.

From his prison cell, Mallory began to write letters in a personal campaign to gain release. He petitioned President Andrew Johnson directly, and enlisted the support of some of his former colleagues in the Senate. A letter from Angela to President Johnson dated November 1865 begged for clemency for her husband due to his ill health.

Johnson was already quite lenient in granting pardons, and the popular clamor for harsh punishment began to recede by the end of the year. On March 10, 1866, Johnson granted Mallory a “partial parole.” Although he was no longer in jail, he was required to stay with his daughter in Bridgeport, Connecticut, until he could take the oath of allegiance to the United States.

In June 1866, Mallory visited Washington, where he called on many of his old friends and political adversaries, including President Johnson and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who received him cordially. He was given permission to return to Florida, but his return was somewhat delayed by problems with his health.

The Mallorys returned to Pensacola, Florida, in July 1866, and Stephen practiced law until his death. Unable to hold elective office by the terms of his parole, he continued to make his opinions known by writing letters and editorials to Florida newspapers. At first he urged acceptance of the reconstituted Union and the policies of Reconstruction, but he soon came out in opposition, particularly against black suffrage.

He had long suffered occasional attacks of gout, and these continued to plague him in the postwar years. In the winter of 1871-1872 he began to complain of his heart, and his health began to deteriorate. Still, he remained active, and the end came rather quickly. He is said to have been listless on November 8, 1873, and that night he began to fail.

Stephen Russell Mallory died on the morning of November 9, 1873, and was buried in St. Michael’s Cemetery in Pensacola.

Angela Moreno Mallory died at Pensacola on March 26, 1901.

SOURCES

Florida Historical Society

Stephen Russell Mallory

Wikipedia: Stephen Mallory

CSA War Department: Stephen Mallory