Wife of Union General Charles Russell Lowell

Josephine Shaw Lowell (1843-1905) was a social reformer who is best known for creating the New York Consumers League in 1890. She recognized that low wages and unemployment were primary causes of poverty, and began to support organized labor and binding arbitration. Lowell raised money for striking garment workers and boycotted stores that underpaid and overworked their salesgirls.

Josephine Shaw Lowell (1843-1905) was a social reformer who is best known for creating the New York Consumers League in 1890. She recognized that low wages and unemployment were primary causes of poverty, and began to support organized labor and binding arbitration. Lowell raised money for striking garment workers and boycotted stores that underpaid and overworked their salesgirls.

Image: Josephine Shaw Lowell in 1869

Josephine Shaw was born on December 16, 1843, in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, into a wealthy New England family. Her parents, Francis George and Sarah Blake Shaw, were philanthropists and intellectuals who encouraged their five children to study, learn and become involved in their communities. The Shaws were wealthy Bostonians with influential friends and relatives, such as poet James Russell Lowell and Margaret Fuller.

From seven to twelve years of age, Josephine lived with her family in Europe, where she attended school at Paris and in a convent at Rome, and became influent in French, Italian and German. After her return, she was in school one year in New York and one year in Boston. The family then moved to Staten Island primarily because Mrs. Shaw needed medical attention for her eyes, and wanted to be near Dr. Elliott, a well-respected doctor in West New Brighton.

Josephine showed an inclination to help others by the time she was thirteen, when she assisted a poor settlement of Irish families in her neighborhood by offering treats at her home. She eagerly joined her mother in working with the Woman’s Central Relief Association in New York City, packing clothing and useful items for soldiers.

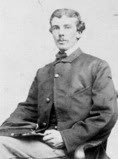

Charles Russell Lowell was born on January 2, 1835, in Boston, Massachusetts, to a family that for more than a century was a guiding force in the history of New England. He was the son of Reverend Charles Russell Lowell, Sr., and nephew of poet James Russell Lowell.

The Lowells were very active in the American Anti-Slavery Society; Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Ralph Waldo Emerson were family friends. But the unexpected bankruptcy of Charles’ father altered the family’s fortunes, and before the son was out of Harvard, he had determined to redeem the family name.

Charles graduated first in the Harvard College class of 1854. He worked in an iron mill in Trenton, New Jersey, for a few months in 1855. After a bout with tuberculosis and a two-year stay in Europe, Lowell turned to the business of making money. Soon after his return he went out West and got involved in the vital new industry of railroading

When the Civil War broke out, Josephine Shaw worked for a branch of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. She kept a diary, which illustrates a keen interest in the affairs of the country, and she was quite concerned with the military successes and failures. She knew many young men from her circle of friends and family who were serving their country, and followed the news very closely.

Charles Russell Lowell entered the Union Army in June 1861, and was commissioned as a captain in the 3rd U.S. Cavalry. An elite young cavalryman, he embodied the promise of his generation. United by education, familial connections and a passionate hatred of slavery, Lowell and his circle of friends enlisted to preserve the Union and to destroy Southern slavery. His letters recount specific military campaigns and relate the motivations that led Northern idealists to wage war against “the vineyards where the grapes of wrath are stored.”

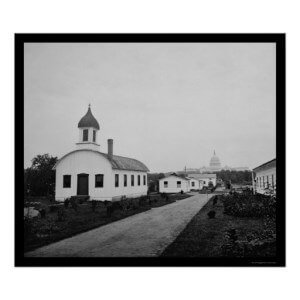

Lowell served on General George B. McClellan‘s staff in 1862. Over the winter of 1862-63, he returned to Boston and helped raise the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry, of which he was appointed Colonel in May 1863. He and his troopers served around Washington DC – active in opposition to Mosby and other Confederate raiders.

On July 18, 1863 Josephine Shaw’s brother, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, was commanding the first African American regiment, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, in Charleston, South Carolina. Short of food and water and under constant fire from well-protected gunners, the soldiers displayed extraordinary courage. Shaw was killed while leading an assault on Fort Wagner, which was portrayed in the 1989 motion picture, Glory, starring Matthew Broderick and Denzel Washington.

Robert Gould Shaw was one of Charles Lowell’s closest friends. After Shaw’s death, Lowell wrote to Josephine, then his fiancee, “I see now that the best Colonel of the best black regiment had to die, it was a sacrifice we owed, and how could it have been paid more gloriously?”

Shaw married Lowell on October 31, 1863, at her father’s home on Staten Island. When Charles returned to the war, she joined him at the front in Virginia to care for the sick and wounded. During the Civil War, she also worked with the American Red Cross and the Women’s Central Association of Relief, which provided aid to Union soldiers.

By early 1864, Colonel Lowell was commanding a cavalry brigade. They joined the Army of the Potomac in the field beginning with the Overland Campaign in May 1864. By July, he was stationed in the Shenandoah Valley. In September, he commanded the Reserve Cavalry Brigade of US and State regiments.

Image: Charles Russell Lowell

An ardent abolitionist and reformer, Colonel Lowell was also a brilliant battlefield strategist, and he turned the tide at the Battle of Cedar Creek in the Valley on October 19, 1864, while serving under General Philip Sheridan. It was a crucial victory for the North, just two weeks before Lincoln’s re-election.

Lowell, however, was mortally wounded at the Battle of Cedar Creek at the age of 29, just days after having been promoted to Brigadier General. After being struck once, he had insisted on remounting his horse and leading a final charge. A second shot through the spine took him down.

Charles Russell Lowell died at dawn on October 20, 1864, only a year after marrying Josephine. Six weeks later their daughter, Carlotta Russell Lowell, was born.

Upon hearing of Lowell’s death, General George Armstrong Custer wept openly. General Sheridan remarked, “I do not think there was a quality which I could have added to Lowell. He was the perfection of a man and a soldier.”

Lowell was selected for promotion to Major General two days after his death. Since he was unable to sign his new commission, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton signed an exception, allowing the posthumus promotion to become official.

For poet James Russell Lowell, four glowing boys, happy, laughing fixtures at Lowell’s home of Elmwood went off to war and did not return: Robert Gould Shaw, William Lowell Putnam, James Jackson Lowell, and Charles Russell Lowell. Lowell had loved them all, perhaps none moreso than his nephew Charles.

After Charles’ death, Josephine and her young daughter Carlotta moved back to Staten Island to live with her parents. She mourned her husband and her brother and started a long correspondence with her brother’s widow, Annie. After the War, Josephine taught former slaves in Virgnina.

Returning to Staten Island, Josephine Shaw Lowell vowed to honor the deaths of her brother and her husband by becoming a social reformer. She came from a distinguished family of abolitionists; her father had organized the Freedmen’s Bureau. She began her lifelong charitable work by seeking to advance African American education; she visited schools as well as hospitals, jails and asylums.

One of her first missions was with the Freedmen’s Association. Lowell and a friend traveled to Virginia with the goal of establishing schools for African Americans in the South. This was just the beginning of her commitment as a force for change in American society.

Josephine became deeply interested in the social problems of New York City, and spent the next thirty-five years visiting prisons and poorhouses, campaigning for parks and better schools, and fighting for civil service reform and the rights of workers. In 1874, she moved to Manhattan with her mother and daughter in order to be nearer the scene of her activities, and where she hoped her daughter would receive a superior education.

Josephine Shaw Lowell, whose tough-minded campaign established the Hudson House of Refuge for Women, saw herself as a radical. Appalled by conditions in New York’s poorhouses and jails, she fought for policies that would eliminate poverty, not just cope with its consequences. She became a leader among the new scientific social reformers, who focused on family patterns as the primary source of poverty and social disorder, and on the role they believed indiscriminate charity played in perpetuating those patterns.

Josephine was committed to social justice and reform, and seized the opportunity to become involved in Progressive reform and the eradication of poverty. She once said, “If the working people had all they ought to have, we should not have the paupers and criminals. It is better to save them before they go under, than to spend your life fishing them out afterward.”

Lowell was a member of the State Charities Aid Society, and her work there and her impressive reports on the need for more adequate facilities for the poor and defenseless caused Governor Samuel J. Tilden in 1876 to appoint her to the New York State Board of Charities, the first woman appointed to that board. She served in this position until 1889, using her post to speak out, lobby, legislate and advocate for people who were unable to do so themselves.

As a result of her tireless work, the first custodial asylum in the country for mentally disabled women was established in 1878. In 1881 legislation was passed which resulted in state reformatories for women. She founded the Charity Organization Society of New York City in 1882, and wrote Public Relief and Private Charity (1884) and Industrial Arbitration and Conciliation (1893).

Although she concentrated on New York, her efforts also affected national services. Her greatest achievement was the founding of the Charity Organization Society of the City of New York, which gave form and direction to all the efforts of distinguished philanthropists in that city and beyond.

Lowell sometimes became angry with others in society, but she never stopped trying. In a letter to her sister-in-law in 1883, she wrote:

Common charity, that is, feeding and clothing people, I am beginning to look upon as wicked! Not in its intention, of course, but in its carelessness and its results, which certainly are to destroy people’s character and make them poorer and poorer. If it could only be drummed into the rich that what the poor want is fair wages and not little doles of food, we should not have all this suffering and misery and vice.

Perhaps Josephine Lowell’s most wide-ranging and effective organization was the New York Consumer’s League which she established in 1890. This organization strove to improve the wages and working conditions of women in New York City, particularly retail clerks. Lowell published a White List that contained a list of stores known to treat women workers well. Initially, the list was very short, but gradually many small businesses joined the League.

In 1889, she left the State Board of Charities to move more freely in other directions. Her interests included the study of methods for mediating labor-management conflicts. Throughout her lifetime, she also founded many charitable organizations including: the New York Charity Organization in 1882, the House of Refuge for Women (later known as the State Training School for Girls) in 1886, the Woman’s Municipal League in 1894, and the Civil Service Reform Association of New York State in 1895.

Josephine’s life was also fulfilled with family and friends. She never remarried and always dressed in black, believing that her first duties were at home. She was opposed to the concept of institutionalization, except as a last resort. She believed that even a poor home was preferable to a good institution. Later in life, she spoke out on more political matters, and in a speech advocating her support for William Jennings Bryan for president, she revealed her passion for patriotism and morality.

Josephine Shaw Lowell died of cancer on October 12, 1905, at her home in New York City. Her memorial service attracted hundreds of people and at least fifty eulogies, as well as articles in numerous daily newspapers. She was buried with her husband at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Image: Josephine Lowell Fountain

Image: Josephine Lowell Fountain

On the Fountain Terrace in Bryant Park behind the New York Public Library is a monument to Lowell – New York City’s first public memorial dedicated to a woman. The classical-style granite fountain was dedicated shortly after her death.

First published in 1907, Life and Letters of Charles Russell Lowell presents the biography and collected correspondence of the nephew of James Russell Lowell. The volume spans both the younger Lowell’s collegiate education and his military service in the American Civil War. His letters begin in 1852 and reveal his values and convictions.

SOURCES

Josephine Shaw Lowell

Captain Charles Russell Lowell

Wikipedia: Charles Russell Lowell

Josephine Shaw Lowell 1843-1905 & Anna Shaw Curtis 1838-1927. Staten Island True Women – Social Reformer and Church Lay Leader, Prepared by Susan McAnanama, a student in Professor Catherine Lavender’s History/Women’s Studies 386 (Women in New York City, 1890-1940) course, The Department of History and The Program in Women’s Studies, The College of Staten Island of The City University of New York.

Biography of Josephine Shaw Lowell