Agnes Maxwell Kearny: Wife of the One-Armed Devil

Agnes Maxwell was born sometime in 1833, daughter of the customs collector for the port of New York City. Her affair with Philip Kearny, who was nearly twice her age, caused quite a scandal in both Paris and New York City. Agnes broke all societal customs by living with Kearny several years before they were married.

Philip Kearny (pronounced CAR-nee) was born June 1, 1815 in New York City, the only child of a wealthy couple, Philip and Susan Watts Kearny. Young Philip lived a privileged childhood, but it was touched by tragedy with the untimely death of his beloved mother when he was eight years old. When his grandfather died, 21-year-old Philip received an inheritance that made him financially independent. Philip chose to pursue a military career.

Kearny obtained his first commission with the cavalry in 1837 as a member of the 1st U.S. Dragoons, stationed at Jefferson Barracks – on the Mississippi River south of St. Louis, Missouri – and Fort Leavenworth – near the town of Leavenworth, Kansas.

With the outbreak of the Mexican War in 1846, Kearny raised a troop of cavalry for the 1st U.S. Dragoons. He spared no expense in outfitting his men. The following year, Kearny led a charge hoping to capture General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna at Churubusco, near Mexico City. Enemy grapeshot shattered Kearny’s left arm; surgeons amputated it at the shoulder.

In 1849, Diana Bullitt Kearny, Philip’s wife of eight years, left him and took their four children to her family’s home in Louisville, Kentucky. At the age of thirty-six, he was suddenly lost. He sounded depressed in this letter to his cousin, John Watts De Peyster:

Had I been as assiduously devoted to wife and children as I was to the Army, I would not today be rootless … sans spouse, sans offspring.

In late 1851, Kearny resigned from the Union Army and embarked on a trip around the world aboard the U.S.S. Vincennes.

Agnes Maxwell

While in Paris, Emperor Louis Napoleon III invited Philip Kearny to a reception given at the Tuileries in May 1853. U.S. Ambassador William Rives introduced Kearny to the Emperor. Louis Napoleon greeted him warmly and thanked him for his service to France during the Algerian War.

That day at the Tuileries, Philip also met 20-year-old Agnes Maxwell, daughter of the customs collector for the port of New York City. Agnes, an auburn-haired beauty, was visiting in Paris with her parents. Although his affair with this young woman created quite a scandal in both Paris and New York, the two were too much in love to relinquish their relationship. He wrote his cousin De Peyster in June 1853:

How incredible that this child should hold such allure for me, a man old enough to be her father … This is a love of autumn and spring … I am nearing my fortieth year … she is barely twenty … I am married, have sired children, and she is affianced to a young man in New York … but I am mesmerized by her loveliness, gentleness and charm … I swear to you … nothing matters … neither gossiping tongues, the variance in our ages nor the obligations we have to others … for she feels about me as I do about her.

Agnes broke her engagement to the man in New York, but Kearny was still a married man and could not marry her. In February 1854, he visited Diana in Kentucky to persuade her to divorce him, but she refused. Kearny began construction on a palatial mansion overlooking the Passaic River in New Jersey; the town that developed around his estate would later be named Kearny.

Defying all conventions, Agnes Maxwell moved in with Kearny and lived with him during the winter of 1854-1855. In the spring they moved to his New Jersey estate, Bellegrove, to escape the disapproval of New York society. Agnes wrote a friend in New York:

Need I give ear to the cackling of hens or the yapping of mongrels? I love Phil, and presently this is the only way I can be with him. I have done nothing of which I am ashamed.

Agnes became pregnant in 1855. Kearny suggested that they attend the coronation of the new Russian Tsar, Alexander II, on March 2, 1856; and then make an extended tour of Europe. They arrived in France in January 1856 and rented an apartment in Rouen, where they were called Monsieur and Madame Philippe Kearny. After a brief stay there, they proceeded to St. Petersburg for the coronation.

The couple traveled to Paris for the birth of their first child, Susan ‘Suzy’ Watts Kearny, who was named after Kearny’s mother, Susan Watts. Philip and Agnes settled at Bellegrove in the early spring of 1857.

Marriage and Family

Early in 1858, Diana finally agreed to Kearny’s demands for a divorce. Angry and hurt over being replaced by such a young woman, Diana stipulated in the divorce decree that Philip could not remarry as long as she lived. Kearny’s lawyers argued that it was only valid in New York State, and he married Agnes in Paris. Their marriage produced three children.

For a time Kearny avoided New York for fear he would be arrested for bigamy. The couple spent the rest of that year in Paris. Kearny wrote, “each day, indeed each moment with Agnes, I savored and enjoyed…” On January 25, 1860, Agnes Maxwell Kearny gave birth to a son whom they named Archibald Kennedy Kearney after Philip’s uncle.

Kearny in the American Civil War

Kearny remained in Paris until April 1861, when the American Civil War began. He had an affinity for upper-class Southerners, but he detested slavery. Agnes and their children accompanied Kearny when he returned home to offer his services to the Union Army.

His left arm was amputated at the shoulder during his service in the Mexican-American War.

The Union was desperate for skilled leaders, but Kearny was virtually ignored: his reputation for difficulty overshadowed his reputation for courage and leadership. The scandal of his relationship with Agnes Maxwell outraged many in the War Department. Realizing he would not be granted a commission in the army, he tried to join as a private but was rejected because his arm had been amputated.

The disastrous Battle of Bull Run shook War Department leaders, and they realized that political appointees serving as generals would not win battles. In July 1861, New Jersey commissioned Philip Kearny as a Brigadier General and placed him in command of the New Jersey Brigade stationed near Alexandria, Virginia. He soon realized that his new brigade was disorganized and undisciplined, which he improved on with constant drills and marches. Kearny also won the loyalty and affection of his men by personally ensuring that they were properly nourished and outfitted. When necessary, he paid for supplies with his own money.

At the beginning of November 1861, Agnes gave birth to another daughter at Bellegrove, whom they named Virginia DeLancey Kearny after the state of Virginia, where her father was serving when she was born.

In February 1862, Kearny received a telegram from Agnes: COME AT ONCE. ARCHIE DESPERATELY ILL WITH TYPHOID. Kearny left at once for Bellegrove, hoping to keep his two-year-old son alive. On February 19, he reached his home. All the medical care available did not save the lad; Archie died on Washington’s Birthday. According to De Peyster, “It appeared as if Phil did not greatly care to live after the death of lovely Archie.”

Within a week he was with his troops again, hiding his heartbreak in hard work. He confided to an aide:

I am an empty vessel. The sky is permanently darkened for me. I shall mourn my boy forever. Yet I cannot forget that Agnes is suffering even more at home without any distraction for her sorrow. At least through duty I am afforded partial oblivion.

In March 1862, General George B. McClellan began the Peninsula Campaign hoping to advance towards Richmond, the Confederate capital. In May, Kearny was appointed commander of the 3rd Division. On March 7, Kearny rode at the head of the New Jersey Brigade. His staff followed behind; among them was a recent West Point graduate, Lieutenant George Armstrong Custer.

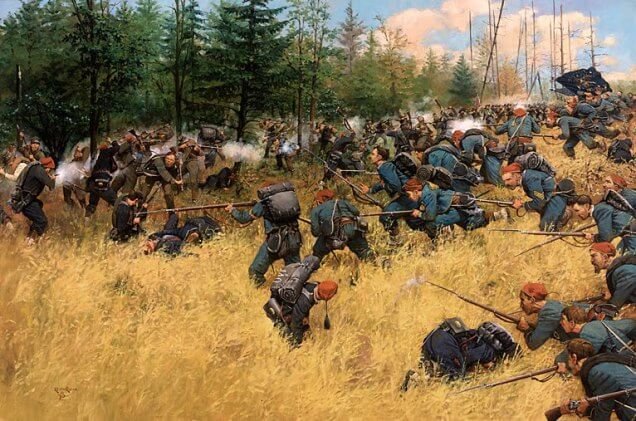

At the Battle of Williamsburg (May 5, 1862), Kearny sent his forces to the aid of General Joseph Hooker. At one point, Kearny’s troops were bogged down by enemy gunfire in a heavily wooded area. He escaped ambushes twice and had at least one horse shot from under him. He rode at the head of his men, holding the reins in his teeth – gun in one hand and sword in the other – as he had learned to ride with the cavalry in France.

One-Armed Devil

General McClellan’s habit of moving cautiously toward the enemy made itself known during the Peninsula Campaign. Kearny wrote to Agnes:

We advance, not as fierce invaders, but like timid trespassers. I know not what the Young Napoleon has in mind. Assuredly he can not hope to capture Richmond by our present actions. The hour calls for audacity. Instead we are offered timorousness.

General Hiram Berry, who commanded the Third Brigade, later wrote:

Phil unloosed a broadside. He pitched into McClellan with language so strong that all who heard it expected he would be placed under arrest until a general court-martial could be held. I was certain Kearny would be relieved of his command on the spot.

McClellan did not respond.

Union forces made another disastrous showing at the Second Battle of Bull Run in late August 1862; this time they were nearly destroyed by General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia.

Battle of Chantilly

The Union army retreated toward Washington, DC and fought with the pursuing Confederates on September 1, 1862, at the Battle of Chantilly. In a violent thunderstorm with lightning and huge sheets of rain, General Kearny decided to investigate a gap in the Union line. He encountered Confederate troops but ignored a demand to surrender. While he tried to escape, a “half dozen muskets fired,” and a Minie ball killed him instantly.

He had learned to fight with pistol in one hand, sword in the other, and reins in his teeth (as shown) from the Chasseur cavalry in France.

Confederate General A.P. Hill ran up to the body with a lantern and exclaimed:

You’ve killed Phil Kearny; he deserved a better fate than to die in the mud.

One of Kearny’s aides, William Styple, wrote in ‘The Death of General Philip Kearny’:

I was Aide de Camp to General Kearny, and accompanied him during the Battle of Chantilly, when he rode on in advance of his Division to see the position occupied by the troops of General [Isaac] Stevens. We rode along the line, and General Kearny sent off one staff officer after another with orders, until I was the only one left with him. We finally arrived at the right of Stevens’ line, where a battery was shelling the opposite woods. The General ordered me to ride at a gallop, back to General Pope … and order him to “double-quick” his brigade to that point and go into line. I did so, and returned as quickly as possible. … The rain was falling fast and darkness was coming on. I inquired of the Battery men which way General Kearny went, and they replied, pointing down to the right and front, “that way.” “My God,” was my exclamation, “we have no troops there, he has ridden right into the enemy lines.” And so it proved. Wishing to know … whether the woods were occupied or not, he rode with his usual bravery, to his death, as we learned from the Confederates, who next day brought in his body under a flag of truce. The General rode up to a whole company of the enemy, paid no attention to their demand that he surrender, wheeled his horse and started back. The whole company fired a volley, but only one bullet struck him; that entered his hip as he lay low along the horse, and came out at the shoulder. And so fell the most picturesque and gallant soldier that it was my fortune to meet during the war.

General Lee, who had admired Kearny since they both served in Mexico, sent Kearny’s body back to Union forces, with a condolence note. There had been rumors in Washington that President Abraham Lincoln was considering replacing George B. McClellan with Kearny.

Many years later Agnes recalled:

The lovely weather on the day of Phil’s funeral saddened me. I remember wishing it had been otherwise … rainy and dismal … I regretted that our [daughters] Suzanne [aged 6] and Virginia [still an enfant] were so young that in a few years they would no longer have any recollection of their father … He was a man worth remembering …

In 1868 Agnes married Admiral John E. Upshur, a widower with several children.

Agnes Maxwell Kearny lived on until July 2, 1917.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Philip Kearny

Life Stories of Civil War Heroes: General Philip Kearny

The Civil War of the United States: Philip Kearny died September 1, 1862

Ohio Civil War Central: Philip Kearny (June 2, 1815 – September 1, 1862)