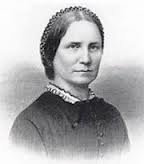

Civil War Nurse and Relief Worker

Jane Currie Blaikie Hoge was a Civil War nurse, sanitary reformer and relief worker who is best remembered for her impressive organizational skills in providing medical supplies and other items to Union soldiers during the Civil War. After seeing some of the deplorable conditions suffered by the troops, Hoge became a leader in sanitary reform, which included activities such as collecting and distributing food, clothing, and medical and hospital supplies. She was also active in recruiting nurses for the army.

Jane Currie Blaikie Hoge was a Civil War nurse, sanitary reformer and relief worker who is best remembered for her impressive organizational skills in providing medical supplies and other items to Union soldiers during the Civil War. After seeing some of the deplorable conditions suffered by the troops, Hoge became a leader in sanitary reform, which included activities such as collecting and distributing food, clothing, and medical and hospital supplies. She was also active in recruiting nurses for the army.

Early Years

Jane Currie Blaikie was born on July 31, 1811 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the daughter of George Blaikie, a wealthy merchant, and Mary Monroe Blaikie. Jane was educated at the Young Ladies’ College, a classical school in Philadelphia, and graduated first in her class. She was also a talented musician.

In June 1831 Jane married Abraham Holmes Hoge, a merchant from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. They had thirteen children, eight of whom reached maturity. Over the next several years, in addition to caring for her large family, Jane was secretary of the Pittsburgh Orphan Asylum. In 1848 the Hoges moved to Chicago, where in 1858 Jane helped found and operate the Home for the Friendless, a refuge for women and children.

Northwestern Sanitary Commission

At the beginning of the Civil War, two of Hoge’s sons enlisted in the Union army. Like many women in both the North and South, she volunteered to help soldiers and the war effort through relief work. In 1861, Jane Hoge met Mary Livermore while nursing soldiers at Camp Douglas, near Chicago. In late 1861, fifty-year-old Jane Hoge, along with Mary Livermore, founded and assumed the management of the Northwestern Sanitary Commission (NWSC) in Chicago, a post she would hold throughout the Civil War.

The Commission was a privately funded effort to improve the morale, logistical support and medical care of men serving in the Union Army. Hoge was already an experienced leader of women’s charitable organizations and probably more prepared for the responsibility than any other woman living in Chicago. Her outspoken demeanor, emboldened by her conviction that the war relief effort needed an efficient mother’s perspective, made her a forceful leader.

Hoge and Livermore were responsible for coordinating aid offered by local relief agencies. About that same time they were also appointed agents of Dorothea Dix, the Superintendent of Army Nurses, to recruit nurses for hospitals in the Western Department (Illinois and the states and territories west of the Mississippi River, as far west as the Rocky Mountains and including New Mexico). They took charge of finding women to be civilian nurses and nurse aides in Union Army facilities.

In 1862 Hoge and Livermore prepared to visit military hospitals on the Mississippi River. In March 1862, on the first of three trips to the Army of the Southwest, Hoge traveled to army hospitals in St. Louis, Missouri; Cairo, Illinois; Mound City, Illinois; and Paducah, Kentucky. The Army of the Southwest served in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the major military and naval operations west of the Mississippi River, except Pacific coast states and territories.

In a lecture given to a meeting of women held at Packer Institute, in Brooklyn, New York, Hoge related this story:

The first great hospital I visited, was Mound City, twelve miles from Cairo. It contained twelve hundred beds, furnished with dainty sheets and pillows, and shirts from the Sanitary Commission, and ornamented with boughs of fresh apple blossoms, placed there by tender female nurses, to refresh the languid frames of their mangled inmates. As I took my slow and solemn walk through this congregation of suffering humanity, I was arrested by the bright blue eyes, and pale but dimpled cheeks, of a boy of nineteen summers. I perceived he was bandaged like a mummy, and could not move a limb; yet still he smiled.

In November 1862 Hoge and Livermore traveled to Washington, DC, representing the Chicago Branch at the Women’s Council, and met with President Abraham Lincoln to discuss their work. On the recommendation of Mark Skinner, president of the Chicago Branch of the Sanitary Commission, Hoge and Livermore were named associate directors of the NWSC in December 1862.

Hoge welcomed the challenge of an overwhelming amount of work. She wrote compelling circulars seeking special supplies and lobbied for aid from societies throughout the Northwest, encouraging women to donate money, clothes, food and medicines. In addition to issuing emotional appeals and providing management and distribution of supplies, Hoge performed nursing and continued her inspection of hospitals. She was unswerving in her devotion to the soldiers, often braving inclement weather and risking disease to help relieve the suffering.

In December 1862, after attending a general conference of U.S. Sanitary Commission leaders in Washington, DC, Hoge and Livermore were officially appointed associate directors of the Chicago branch. The work demanded of them was great and ceaseless. By letters, lectures and other means they managed the work of upwards of a thousand local aid societies throughout the Northwest in collecting and forwarding clothing, medical and hospital supplies, food and other materials.

Hoge’s wartime job drew her further into public life than she had previously ventured. She traveled, made speeches, raised large amounts of money, worked with both civilians and military personnel, helped manage the commission’s daily business deals, and organized the myriad donated supplies destined for the western armies.

Scurvy, a disease caused by a deficiency of vitamin C, had become a leading cause of suffering and death among the soldiers of the Union Army. Although nothing was known about vitamins at the time, Hoge and Livermore realized that without vegetables or fruit, soldiers were developing scurvy. Onions and potatoes that could be eaten raw seemed the most practical way to protect soldiers from that dreaded disease.

In spring 1863 Hoge Hoge launched a campaign to collect vegetables for the troops by publicizing graphic descriptions of the stages of scurvy in small-town newspapers, and launching slogans such as, “A barrel of potatoes for every soldier.” She acted as a liaison between the army and the homefront, securing a thousand bushels of vegetables to combat scurvy.

In June 1863 Hoge traveled to Vicksburg, where one of her sons, a colonel in the 113th Regiment Illinois Volunteers, had been wounded. Combining her inspection of the logistics system with the nursing of soldiers, Hoge cared for her son, talked to soldiers, sang hymns with them, and promised to deliver messages to their families. Potatoes and onions were transported by ship to Vicksburg, where they were reputed to help secure the surrender of the city the following month.

Northwestern Sanitary Fair

By 1863, Jane Hoge and Mary Livermore had emerged as the leaders of Chicago’s Northwestern Sanitary Commission; by the summer of 1863, they believed that they had exhausted every means of fundraising in their part of the country. Their creative idea for increasing revenue would forever change fundraising events across the country. They decided that a “grand fair, in which the whole Northwest would unite” might attract large crowds and raise up to $25,000.

Working with Livermore, Eliza Porter and other relief workers, Hoge hoped through the fair to secure enough donations to establish a soldiers’ home in Chicago. The ladies presented the gentlemen of the commission with their idea, but they laughed at their proposal to raise $25,000 from the event. On September 1, they hosted a convention in Chicago where they decided on the date and location of the fair, which would be produced entirely by women.

After arrangements were completed, the two women turned to President Lincoln for a donation. They were no strangers to the President. Mary Livermore was the wife of the editor of the Chicago-based New Covenant, where she also worked as an editor and writer. She was the only woman journalist who covered the nomination of Abraham Lincoln at the Republican National Convention in Chicago in May 1860. Also, in November 1862, Livermore and Hoge had met with the president as representatives of the Sanitary Commission’s Council of Women.

On October 11, 1863, sixteen days before the Sanitary Fair’s grand opening, Mary Livermore wrote to Lincoln requesting a donation for the fair:

It has been suggested to us from various quarters that the most acceptable donation you could possibly make, would be the original manuscript of the Proclamation of Emancipation and I have been instructed to ask for this, if it is at all consistent with what is proper for you to donate. There would seem great appropriateness in this gift to Chicago, or Illinois, for the benefit of our Western soldiers, coming as it would from a Western President.

President Lincoln responded to the women on October 26:

According to the request made in your behalf, the original draft of the Emancipation Proclamation is herewith enclosed. The formal words at the top, and the conclusion, except the signature, you perceive are not in my handwriting. They were written at the State Department by whom I know not. The printed part was cut from a copy of the preliminary proclamation, and pasted on merely to save writing. I had some desire to retain the paper; but if it shall contribute to the relief or comfort of the soldiers that will be better.

Though few believed it possible, Hoge and Livermore staged the first Sanitary Fair in Chicago in October 1863 and received numerous donations and support from local businesses. The two-week fair opened on October 27, 1863, featuring parades, food and entertainment. The sanitary workers sold donated produce and other goods, and charged fifty cents for admission to the fair’s many exhibits. The tattered battle flags of six Wisconsin units, including the Iron Brigade’s Second and Sixth Wisconsin regiments, were displayed on the east wall of the Cook County Court House.

On the second day of the fair, Livermore recalled:

On unlocking my post–office drawer that morning I found the precious document, and carried it triumphantly to Bryan Hall (partitioned as a sales and exhibition room and dining area), one of the six halls occupied by the fair, where the package was opened. The manuscript of the Proclamation was accompanied by a characteristic letter, which I have given elsewhere.

This document, principally in Lincoln’s handwriting, was the final draft of the final version; Lincoln had photographic copies made prior to relinquishing it. Hoge announced the arrival of the document to the “immense throngs crowding the building, who welcomed it with deafening cheers.” Livermore framed the document “in an elegant black walnut frame, so arranged that it could be read entirely through the plate glass that protected it from touch, and hung where it could be seen and read by all.”

On November 11th Hoge and Livermore wrote to Lincoln expressing their deepest gratitude for such a generous gift:

We profoundly thank you for your gift to our Northwestern Fair of the original draft of the Proclamation of Emancipation. It came to us in the midst of the wonderful outpouring of loyalty and liberality, from the great throbbing heart of the North West, nay, almost of the nation; for all seemed ready to respond and give. Your proclamation is the star of hope, the rainbow of promise, that has risen above the din and carnage of this unholy rebellion, and will fill the brightest page in the history of our struggle for national existence… to the oppressed of every land, at home and abroad.

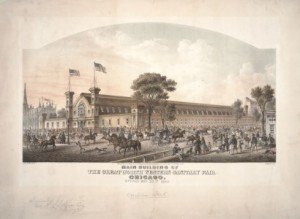

The Northwestern Sanitary Fair – the first of its kind – raised nearly $100,000. It also inspired a wave of similar fairs across the North including the one depicted below, the Great Northwestern Sanitary Fair of 1865, the second sanitary fair held in Chicago, which raised over $200,000.

Image: Great Northwestern Sanitary Fair

After the fair, Jane Hoge continued to travel with Livermore, and they became household names. She attended the January 1864 Council of Women in Washington, DC, at which she recounted her experiences with aid societies. As the war waned, Hoge continued speaking. She praised the “self-denying liberality, labor and zeal of thousands of our countrywomen” who assisted soldiers and wanted to “offer an example, calculated to stimulate and encourage women in all time to come.”

After the war, Jane Hoge received numerous public tributes. In 1867 Jane Hoge published her memoir, The Boys in Blue; or Heroes of the Rank & File (1867), one of the first accounts to be written by a woman relief worker; the book heaped praise on the enlisted men, not officers. The emotional rhetoric and patriotic imagery biased her account, but historians still consider it valuable. She said that she wrote the book because “justice to the soldier, and historical accuracy, compel me to represent affairs as they were, thus placing the honor and the shame where they justly belong.”

She also used the skills and reputation she had garnered during the war to continue her charitable works. In 1869 she and a group of women opened the Chicago Home for the Friendless to provide shelter and aid for impoverished women and children, especially foundlings, wards of the court and the elderly.

In 1871 she organized a fund-raising campaign that financed the founding of the Evanston (Illinois) College for Ladies, which opened later that year under the direction of educator and suffragist Frances Willard. Hoge served on the college’s board of trustees until it merged with Northwestern University in 1874. She also served as head of the Women’s Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions in the Northwest for thirteen years (1872-1885).

Jane Currie Blaikie Hoge died in Chicago on August 26, 1890 at age 79.

A very efficient organizer, Jane Hoge made great strides in relieving the suffering of Union soldiers during the Civil War. With an unflagging energy and devotion to the cause, she often battled bad weather and disease to provide relief for the sick and dying. She was always able to secure supplies and food when they were desperately needed. She was a true humanitarian.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Jane Currie Blaikie Hoge

H-Net Online: Jane Currie Blaikie Hoge

The Sanitary Fair’s Gifts to President Lincoln

Encyclopedia Britannica: Jane Currie Blaikie Hoge