Civil War Nurse and Feminist

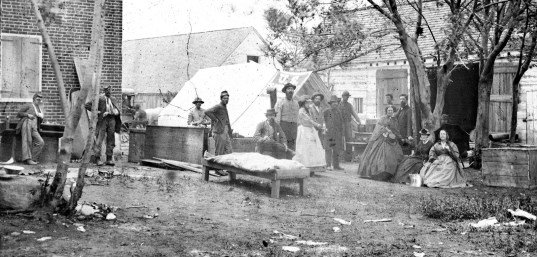

During the Civil War, Mary Livermore organized a volunteer support network for the Union hospitals, wrote letters for wounded soldiers, escorted wounded soldiers from hospitals to their homes, and raised large sums of money to support the work of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. Livermore worked closely with Mary Ann Bickerdyke who was chief of nursing under the command of General Ulysses S. Grant and General William T. Sherman during the Atlanta Campaign.

During the Civil War, Mary Livermore organized a volunteer support network for the Union hospitals, wrote letters for wounded soldiers, escorted wounded soldiers from hospitals to their homes, and raised large sums of money to support the work of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. Livermore worked closely with Mary Ann Bickerdyke who was chief of nursing under the command of General Ulysses S. Grant and General William T. Sherman during the Atlanta Campaign.

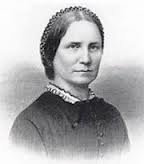

Mary Ashton Rice was born in Boston on December 19, 1820, into a strict Calvinist Baptist family, took religious questions seriously as a child. She liked to pretend to be a preacher, using the kitchen table as her pulpit, and if she could find no live audience, would “go alone to the wood shed, arrange the unsplit logs in rows as pews, and the split sticks as an audience occupying them, and then mount a box, which served for a pulpit, and preach, and pray, and sing by the hour.”

She was troubled by the doctrine of predestination and became haunted by a fear of death and the hereafter. As a young woman, she was plunged into deep depression by the death of a sister whom she feared might not have been among the elect. Her minister and her father were unable to provide her any real comfort.

Mary attended the Female Seminary in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where she taught for two years after her graduation in 1836. In 1839, she found work as a tutor on a Virginia plantation. She learned that slavery was as “demoralizing and debasing” to white slaveowners as it was hard and painful for blacks. She witnessed the brutal whipping of a cooper named Matt, and was ill for days afterward. By the time she returned to New England, Mary was a strong opponent of slavery.

In 1842, Mary took charge of a private school in Duxbury, Massachusetts, and worked there for three years before marrying Daniel Livermore, a Universalist minister, in May 1845. For the next three years, the couple worked among factory workers providing education and health care.

The Livermores moved frequently during the early years of their marriage, because Daniel served at several churches in Massachusetts and New York. Daniel’s beliefs concerning slavery, women’s rights and temperance often caused tension with his parishioners.

Mary strongly supported her husband’s views, but she was unhappy with her role of minister’s wife. She found an outlet in writing and won two prizes for her stories—Thirty Years too Late in 1845 and A Mental Transformation in 1848, about “changes wrought in one’s life and character by a vital change of religious belief.” During the next 10 years, she wrote for various religious and reform periodicals.

The Livermores decided to immigrate to Kansas in 1857, but their daughter’s illness ended their journey at Chicago, where for 12 years they edited the New Covenant, a Unitarian periodical. Mary served as associate editor. She also published a collection of essays entitled Pen Pictures.

In 1857, frustrated with parish life, the couple moved with their two surviving daughters to Chicago, while Daniel explored the possibility of moving to Kansas to help establish an antislavery colony. The illness of their younger daughter caused them to abandon the plan, and they made Chicago their home for the next thirteen years.

It was during this period that Mary, with Daniel’s help and encouragement, came into her own as a self-confident woman with an important role to play in the reshaping of society. A turning point came when, during a cholera epidemic in the city, she decided to stay and volunteer her help. She quickly developed organizational skills.

When the Civil War broke out, Mary immediately volunteered her services. Early in 1862, Mary and her friend Jane Hoge visited several military hospitals, and in December of that year they were made co-directors of the Chicago branch of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. She and Jane organized a Sanitary Fair that raised more than $70,000, and inspired similar efforts in several other cities.

Through her work with the Sanitary Commission, Mary became convinced that extending the right to vote (suffrage) to women was the key to many social reforms. In her memoir of the war, My Story of the War: A Woman’s Narrative of Four Years Personal Experience of the Sanitary Service of the Rebellion, she wrote:

In the early summer of 1863, frequent calls of business took me through the extensive farming districts of Wisconsin, and Eastern Iowa, where the farmers were the busiest, gathering the wheat harvest. As we dashed along the railway, let our course lead in whatever it might, it took us through what seemed a continuous wheatfield.

The yellow grain was waving everywhere, and two-horse reapers were cutting it down in a wholesale fashion that would have astonished Eastern farmers. Hundreds of reapers could be counted in a tide of half a dozen hours. The crops were generally good, and in some instances heavy, and every man and boy was pressed into service to secure the abundant harvest while the weather was fine.

Women were in the field everywhere, driving the reapers, binding and shocking, and loading grain, until then an unusual sight. At first, it displeased me, and I turned away in aversion. By and by, I observed how skillfully they drove the horses round and round the wheatfields, diminishing more and more its periphery at every circuit, the glittering blades of the reaper cutting wide swaths with a rapid, clicking sound, that was pleasant to hear.

Then I saw that when they followed the reapers binding and shocking although they did not keep up with the men, their work was done with more precision and nicety, and the sheaves had an artistic finish that those lacked made by the men. So I said to myself, “They are worthy women, and deserve praise; their husbands are probably too poor to hire help, and, like the “helpmeets” God designed them to be, they have girt themselves to this work—and they are doing it superbly. Good wives! Good women!”

When the war ended, Mary rose to leadership in the women’s suffrage movement, writing and traveling widely as she lectured and chaired meetings. In 1868, she organized the first suffrage convention held in Chicago. She launched the Agitator, a suffragist paper, in January 1869. Later in the year, she attended the founding convention of the American Woman Suffrage Association in Cleveland, Ohio, and was elected vice president.

In 1870, the couple moved to Melrose, Massachusetts, where Mary co-edited of the Woman’s Journal with Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe.

But it was not long before James Redpath, head of the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, urged her to devote all of her efforts to public speaking. Daniel urged her to accept the invitation. For almost a quarter of a century, Mary lectured about women’s rights and other reform topics “in every part of the country from Maine to Santa Barbara.”

Mary’s lectures, delivered without manuscript or notes, addressed a wide variety of topics. “Concerning Husbands and Wives” advocated a marriage between equal partners. In “The Battle of Life,” she shared her vision of the better world that was to come. In “What shall we do with our Daughters?” she urged her listeners to prepare the next generation of women to take their rightful place in the affairs of the world.

The Livermores planned their lives carefully, with Daniel doing library research for Mary’s lectures and joining her at regular intervals when she was traveling on the circuit. They also took several trips abroad together.

She was president of the Association for the Advancement of Women in 1873, and of the Massachusetts Woman’s Christian Temperance Union from 1875 to 1885. A founding member of the American Woman Suffrage Association, Mary served as its president between 1875 and 1878.

In 1895, Mary retired from the lecture circuit and wrote her autobiography, The Story of My Life: The Sunshine and Shadow of Seventy Years, which was published in 1897.

Mary Ashton Livermore died at her home in Melrose, Massachusetts, on May 23, 1905, at the age of 84.

SOURCES

The Outcome of this Faith

Women’s Rights and Black Liberation