Women’s Rights Advocates

The first women who fought for their civil and legal rights were not a unique breed. Many were wives and mothers like most other females in the mid-nineteenth century. However, they must have developed a strong sense of self and some support from their husbands, for they found time in their busy lives to protest against the confining space that society had assigned them: women’s sphere.

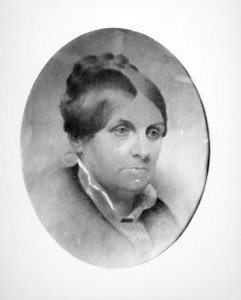

May Wright Sewall (1844 – 1920)

Born May Eliza Wright May 27, 1844 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, May graduated in 1866 from North-Western Female College in Evanston, Illinois. There she earned a Bachelor of Science degree and a Master of Arts in 1871 and began a career in teaching – in Mississippi and Michigan. She later took a position at A high school in Franklin, Indiana and married the school’s principal, Edwin Thompson.

The couple then moved to Indianapolis, Indiana, where they taught at the old Indianapolis High School. After Edwin died of tuberculosis, May married educator Theodore Sewall in 1880. In 1882 she and her husband founded the Girls’ Classical School of Indianapolis, with which she was associated for a quarter of a century.

Although she had a successful career in education, May Wright Sewall was best-known as a women’s rights activist – in her home state of Indiana and nationally. Starting her career as a suffragist in the 1870s, she helped found the Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society in 1878. In the early 1880s, Sewall led a campaign that narrowly failed to secure voting rights for women in Indiana. From 1882 to 1890 she served as chairman of the executive committee of the National Woman Suffrage Association and began a relationship with women’s suffrage leaders Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

In 1888 Sewall and Frances Willard were charged with the task of holding a convention in Washington, DC to mark the fortieth anniversary of the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York in July 1848. In 1889 Sewall helped organize the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. Two other organizations emerged at that time. Sewall served as president of the National Council of Women from 1897 through 1899 and was elected to that office in the International Council of Women from 1899 to 1904.

During 1891 and 1892 she traveled to Europe to build support for the World’s Congress of Representative Women to be held at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois in 1893. Sewall spent her late years to the cause of peace.

In the introduction to May Wright Sewall’s book, Neither Dead nor Sleeping (1920), American novelist Booth Tarkington stated that the “three most prominent citizens” of Indianapolis in their day were Benjamin Harrison, James Whitcomb Riley and May Wright Sewall.

May Wright Sewall died on July 22, 1920, one month before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, granting women the right to vote.

Pauline Agassiz Shaw (1841-1917)

Pauline Agassiz was born February 6, 1841 in Neuchatel, Switzerland and was raised by a family of intellectuals. Her father, well-known paleontologist and geologist Louis Agassiz, traveled to America to lecture at Harvard University in 1846. He was still there two years later when his German-born mother Cecile Braun Agassiz died of tuberculosis. Relatives cared for the Agassiz children – Pauline, Alexander, and Ida – until 1850, when Louis Agassiz married Elizabeth Cary, and the children moved in with the couple in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

By George Elgar Hicks

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven CT

Elizabeth Cary Agassiz – a strong woman in her own right – opened a school for girls in their home in 1855, and she educated Pauline there. Louis Agassiz and some of his fellow professors at Harvard taught there, and the school quickly gained an excellent reputation. Among Pauline’s classmates was photographer Clover Adams.

On November 13, 1860, as the American Civil War was beginning, nineteen-year-old Pauline Agassiz married businessman Quincy Adams Shaw, a wealthy Harvard graduate. Quincy Shaw invested in mines with Pauline’s brother and profits from that venture earned him one of the largest fortunes in Boston. This wealth allowed the couple and their five children – Louis Agassiz, Pauline, Marian, Quincy Adams, and Robert Gould Shaw – to live on a sprawling estate in what is now the Jamaica Plain neighborhood in Boston.

Her wealth allowed Pauline Agassiz Shaw to devote herself to philanthropy in the field of children’s education for many years. From her estate in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood, she contributed money that helped build schools and daycare facilities. As one Bostonian noted, she dedicated her life and fortune to “the education of the child and of the mother and of the community.”

During the last quarter of the 19th century, Shaw began contributing large sums to her other favorite cause: women’s suffrage. She believed that achieving the vote would also get women involved in reform movements. In 1901 Shaw founded the Boston Equal Suffrage Association for Good Government and served as its president for the rest of her life. She gave generous amounts to suffrage campaigns both at home and in other states and to keep publishing the Woman’s Journal, the weekly suffrage paper published by Alice Stone Blackwell, sister of women’s rights powerhouse Lucy Stone.

Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826-1898)

Matilda Joslyn Gage was a 19th-century women’s rights activist, abolitionist, and prolific writer. She worked tirelessly for her social reform causes, became an inspiring public speaker; and contributed numerous articles to the press, being regarded as “one of the most logical, fearless and scientific writers of her day.”

Matilda Joslyn Gage pledged her life to the women’s rights movement at a national women’s rights convention in Syracuse, New York in September 1852 and made her first public speech about the rights of women there. This is an excerpt from that speech:

Let us look at the rights it is boasted women now possess. After marriage, the husband and wife are considered as one person in law, which I hold to be false, from the very laws applicable to married parties. Were it so, the act of one would be as binding as the acts of the other, and wise legislators would not meet to enact statutes defining the peculiar rights of each; were it so, a woman could not legally be a man’s inferior. Such a thing would be a veritable impossibility. One half of a person can not be under the protection or direction of the other half. …

A wife can not, by will, devise lands to her husband; for at the time of such act, she is supposed to be under his coercion, and therefore all deeds executed, and acts done by her, during her coverture, are void, except it be those where she is solely and directly examined, to learn if her act be voluntary! How degrading! how humiliating! and carrying on the face of it, crying injustice, is the position woman is compelled to assume, when thus taken aside, by the magistrate, and asked, “Do you sign this deed of your own free will and accord, and not by fear and compulsion of your husband?” Out upon it! Why the very stones would cry out should woman longer hold her peace.

In May 1869, Gage was a founding member of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and served in various offices of that organization for twenty years (1869-1889). From 1878 to 1881 she published the National Citizen and Ballot Box, the NWSA’s official newspaper, from her home in Fayetteville, New York. Gage also worked as a correspondent for newspapers from New York to California, primarily writing about women’s rights issues and activities. With Stanton, she co-authored the major documents of the NWSA.

When Susan B. Anthony voted in the 1872 presidential election and was arrested for it; Gage was the only suffragist who came to Anthony’s aid, supporting her during her trial, speaking out on her behalf, and writing an analysis of the case for the Albany Law Journal.

Gage wore many hats. She served as president of the New York State Suffrage Association for five years and president of the National Woman Suffrage Association from 1875 to 1876. She also held the office of second vice-president, vice-president-at-large and chairman of the executive committee of the original National Woman Suffrage Association.

Concerned that women had been written out of history, Gage documented many previously unacknowledged accomplishments of her sex, including Catherine Littlefield Greene‘s invention of the cotton gin, wrongly attributed to Eli Whitney, and Anna Ella Carroll‘s detailed planning of the crucial Tennessee Campaign of the Civil war, generally credited to General Ulysses S Grant. Gage authored the influential pamphlets Woman as Inventor (1870), Woman’s Rights Catechism (1871), and Who Planned the Tennessee Campaign of 1862? (1880).

The slow pace of suffrage efforts during the 1880s discouraged Gage, and the religious movement that hoped to establish a Christian nation alarmed her. She formed the Women’s National Liberal Union in 1890 to combat efforts to unite church and state. Her masterwork, Woman, Church and State (1893), articulates her views.

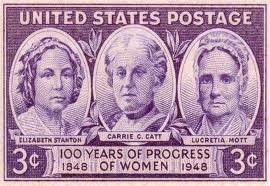

Delegates from nine countries worked across national boundaries advocating human rights for women.

Seated second from right: Matilda Joslyn Gage; third from right: Elizabeth Cady Stanton; second from left: Susan B. Anthony.

Gage co-edited with Stanton and Anthony the first three volumes of the six-volume The History of Woman Suffrage (1881-1887), much of the writing was done in Gage’s Fayetteville home. “The three names,” predicted a women’s rights newspaper, “will ever hold a grateful place in the hearts of posterity.” Susan B. Anthony spent so much time in the Gage house that the family called the guest bedroom the ‘Susan B. Anthony Room.’ Anthony wrote her name with a diamond in the upstairs library window on one of her visits; it is still there.

Matilda Joslyn Gage died on March 18, 1898, while visiting her daughter’s home in Chicago, Illinois. Gage’s lifelong motto can be seen on her gravestone in the Fayetteville cemetery, a short walk from her home: There is a word sweeter than Mother, Home or Heaven; that word is Liberty.

SOURCES

IN.gov: May Wright Sewall

Wikipedia: Matilda Joslyn Gage

Encyclopedia: Pauline Agassiz Shaw

Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation: Women’s Rights Room