First First Lady to Support Women’s Rights

Caroline Harrison, the wife of President Benjamin Harrison, was First Lady from 1889 until her death. She is remembered for her efforts to refurbish the aging White House. Her public support of women’s rights and higher education for women focused greater attention on those issue and promoted greater acceptance of a First Lady’s political ideals.

Caroline Harrison, the wife of President Benjamin Harrison, was First Lady from 1889 until her death. She is remembered for her efforts to refurbish the aging White House. Her public support of women’s rights and higher education for women focused greater attention on those issue and promoted greater acceptance of a First Lady’s political ideals.

Early Years

Caroline Scott was born on October 1, 1832 in Oxford, Ohio, the second daughter of Mary Potts Neal and John Witherspoon Scott, a minister and professor of science and math at Miami University in Oxford. Along with two sisters and two brothers, Carrie, as she was called by friends and family, was raised in a modest, middle-class family.

Wherever they lived, the house was filled with books, art and music. Although the family was not well-off, her father ensured that his daughters as well as his sons were well educated. Caroline’s talents in art and music were nurtured from early childhood. Her Aunt Caroline Neal often visited the Scott home and gave her niece many hours of instruction in drawing.

After more than two decades at Miami University, in 1845 Dr. Scott and several other professors were fired from their positions after a dispute with the university president, George Junkin, over the issue of slavery; Junkin supported it and Scott and the others opposed it. (Dr. Scott was suspected of harboring runaway slaves.)

Dr. Scott moved his family to Cincinnati where he taught chemistry and physics at the Farmers’ College at College Hill, near Cincinnati. There in 1848 Caroline met Benjamin Harrison, one of her father’s freshman students. Harrison’s great-grandfather Benjamin Harrison was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and his grandfather William Henry Harrison was the ninth president of the United States.

In 1849, the Scotts moved back to Oxford, where Dr. Scott opened the Oxford Female Institute, which was held in the former Temperance Tavern, which he had purchased in 1841 with the intention of opening a girls’ school. Caroline’s mother Mary Neal Scott joined the school as its matron and the Head of Home Economics.

Caroline enrolled as a student at the Institute, studying English literature, for which she developed a life-long love, in addition to theater, music art and painting. She loved painting, first watercolors and then china painting, and she painted for the rest of her life.

Courtship

Young Benjamin Harrison, or Ben as he was known, had studied under Dr. Scott at Farmers’ College for nearly two years. In 1850, he transferred to Miami University, both because of its strong academic program and to be near Caroline. Brown-haired, petite and witty – she infatuated the reserved young man.

Benjamin was serious almost to the point of being solemn, while Caroline was lighthearted, humorous and had a sparkling personality. She encouraged him to be more relaxed and, against her father’s wishes, took him to dances. She later said that she had no patience with her church’s ban on dancing.

The couple became engaged during the second semester of Benjamin’s senior year, but they decided to postpone their wedding while he studied law in the law office of Storer & Gwynne in Cincinnati and she finished school. In 1852, Caroline joined the faculty at Oxford Female Institute as an Assistant in Piano Music. She graduated in 1853 with a degree in music.

That year she moved to Carrollton, Kentucky, where she taught music for a year, during which time she suffered terribly from pneumonia. She easily became depressed when she was not well and suffered from upper respiratory problems for the rest of her life. Benjamin was concerned about her, and persuaded her to return to Ohio.

Marriage and Family

Caroline Scott and Benjamin Harrison were married on October 20, 1853 at the Scott family home, with her father officiating. She was 21 years old. The newlyweds lived at the Harrison family home at North Bend, Ohio for some time. After Benjamin completed his law studies a year later, they moved to Indianapolis, Indiana, where he set up his first practice.

The first few years of their marriage were a struggle. The couple rarely spent time together, as Benjamin worked to establish his law practice and was active in fraternal organizations to help build up his business. While Caroline was pregnant, she returned to Oxford to stay with her parents, a common practice at the time. In 1854, their first child Russell Benjamin Harrison was born.

Caroline soon returned to Indianapolis. Not long after, a fire destroyed the Harrison home and all their belongings. The family managed to recover financially after Benjamin took a job handling cases for a local law firm whose founder had decided to run for office. In 1858, Caroline gave birth to a daughter, Mary Scott Harrison. In 1861 she gave birth to a second daughter, who died soon after birth.

While Benjamin Harrison became a man of note in his profession, Caroline cared for their children and was active in the First Presbyterian Church and an orphans’ home. Blessed with considerable artistic talent, she especially enjoyed painting for recreation. However, Benjamin’s long hours at the law office and his pursuit of a living drove a wall between the young couple. Caroline did not complain, but the strain showed.

The Civil War

At the onset of the Civil War, both Harrisons sought to help in the war effort. Caroline joined Indianapolis groups such as the Ladies Patriotic Association and the Ladies Sanitary Committee, which helped care for wounded soldiers directly and raised money for their care and supplies. At the same time, she joined the church choir and raised their two children.

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued a call for more recruits. Benjamin Harrison recruited a regiment of over 1,000 men from Indiana. Initially offered the command, he declined because of lack of military experience and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. During the day, he trained his men, and at night he studied military strategy.

In August 1862, when the regiment left Indiana to join the Union Army at Louisville, Kentucky, Harrison was promoted to the rank of colonel, and his regiment was commissioned as the 70th Indiana Infantry. For much of its first two years, the 70th Indiana performed reconnaissance duty and guarded railroads in Kentucky and Tennessee.

In May 1864, the 70th Indiana regiment joined General William Tecumseh Sherman‘s Atlanta Campaign and moved to the front lines, and Harrison was promoted to command the 1st Brigade of the 1st Division of the XX Corps. From May through July 1864, his brigade fought at the Battles of Resace, Cassville, New Hope Church, Lost Mountain, Kennesaw Mountain, Marietta, Peachtree Creek and Atlanta.

When Sherman’s main force began its March to the Sea in November 1864, Harrison’s brigade was transferred to the District of Etowah and participated in the Battle of Nashville in December 1864. On March 22, 1865, Harrison earned his final promotion, to the rank of brigadier general, and he rode in the Grand Review in Washington, DC before mustering out on June 8, 1865.

Apparently the Civil War and its horrors taught Benjamin Harrison to value what was really important in life. His letters to Caroline during the war are filled with a deep passionate tone. When he returned home, she would never again reproach him for neglect. His law practice and his fame grew, and he became a political force.

Political Life

After the war, Benjamin Harrison spent the next decade practicing law and getting involved in politics. He ran for governor of Indiana in 1876, but lost. Even in the midst of politics, parties and receptions, Caroline pursued her art work, gardening and Impromptu Club. The Harrison home on North Delaware Street in Indianapolis, Indiana was built in 1874-75, and soon became a center of activity.

Image: The Harrison Home

Indianapolis, Indiana

Her husband’s election to the Senate in 1880 brought Caroline Harrison to Washington, DC, but a serious fall that year undermined her health. In 1883, she had surgery in New York and required a lengthy period of recovery. She had also suffered from respiratory problems since her bout with pneumonia in her youth, and did not participate much in Washington’s winter social season.

In the fall of 1887 Harrison was nominated for President by the Republican Party. In the campaign, Caroline was a definite asset. Her charm, naturalness and open manner offset her husband’s chilly reserve, and she spoke often to members of the press. Their financial situation was still precarious, causing her to joke once, “Well, husband, it’s either to the White House with us or the poor house.” In November 1888, Harrison defeated the incumbent Grover Cleveland.

First Lady of the United States (1889-1892)

Caroline Harrison was 56 years old when she became first lady in 1881. Like Elizabeth Monroe (1817-1825), Caroline Harrison coped with the challenge of following a very popular First Lady. The public had adored both Dolley Madison (Monroe’s predecessor) and Frances Cleveland (Caroline’s predecessor) and was critical of the First Ladies who followed them.

The First Lady was noted for her elegant White House receptions and dinners, but she is most remembered for her efforts to refurbish the aging White House. She was horrified at the filth and clutter and at first she wanted to have it torn down and replaced. She then made up very detailed plans to enlarge the existing building by adding an East Wing and and a West Wing so that the original mansion could be used for entertaining and the family’s living area.

Instead, the new First Lady had to be content with a budget that barely covered the expenses for housecleaning and minor repairs, but she did what she could. She bought new curtains and furniture, renovated the kitchen, laid new floors, and installed private baths and a new heating system. In 1891 electricity was installed in the White House.

As she worked to remodel the White House, Caroline was careful to inventory the contents of every room. She cataloged the mansion’s furniture, pictures and decorative objects, working to preserve those that had historical value. In particular, she unearthed the chinaware of former presidential administrations and cleaned, repaired and identified which pieces belonged to which First Lady.

During the Harrison administration, their daughter Mary Harrison McKee (widow of James Robert McKee, co-founder of the company that became General Electric), her two children, Caroline’s father and other relatives lived at the White House. Caroline’s widowed niece Mary Lord Dimmick moved into the White House to serve as secretary to the First Lady in 1889.

Caroline’s sister died in early December 1889 at the executive mansion, but Caroline went ahead with her plans to raise the first Christmas tree in the White House, as the custom was becoming more popular. She had John Phillip Sousa and the Marine Band play and, for the first time since Sarah Polk was First Lady, there was dancing in the White House.

Daughters of the American Revolution

Women’s rights would become another one of the First Lady’s passions. Caroline Harrison firmly believed that women should pursue activities outside the home and lived according to that creed. The centennial of President George Washington‘s inauguration in 1889 heightened the nation’s interest in the heroic past of the White House.

In 1890 she lent her prestige as First Lady to the founding of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR) and served as its first President General, regarding it as a potentially “powerful political force for women.” In February 1892, Caroline gave the first recorded speech by a First Lady at the first Congress of the NSDAR. This is an excerpt:

We have within ourselves the only element of destruction; our foes are from within, not without. It has been said “that the men to make a country are made by self-denial;” and is it not true that this Society, to live and grow and become what we would desire it to be, must be composed of self-denying women? Our hope is in unity and self-sacrifice.

Since this Society has been organized, and so much thought and reading directed to the early struggle of this country, it has been made plain that much of its success was due to the character of the women of that era. The unselfish part they acted constantly commends itself to our admiration and example. If there is no abatement in this element of success in our ranks I feel sure their daughters can perpetuate a society worthy the cause and worthy themselves.

Women’s Medical School Fund Committee

The Women’s Medical School Fund Committee was officially formed in May 1890, and was backed by big money from railroad heiress Mary Elizabeth Garrett and prestigious names including former First Lady Louisa Adams and suffragist Julia Ward Howe. The Committee then approached the struggling Johns Hopkins University with a plan to underwrite its new School of Medicine – provided that women were admitted on a basis equal to men, and stipulating that the funds would be forfeited if the terms of the endowment were not followed.

The Committee soon embarked upon a massive fundraising and public relations campaign. The core group asked the most prominent women in each city to head their committee. In Washington, DC, Caroline Harrison served as chairman, her address listed only as The White House.

The First Lady became perhaps the most prominent signatory and one of the most outspoken advocates for the Women’s Medical School Fund Committee. She hosted receptions and fundraisers for them. She did a painting of orchids, turned it into a print and made it available for sale, helping her committee raise $100,000 for the new school. The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine opened in 1893, and has always welcomed students of both genders.

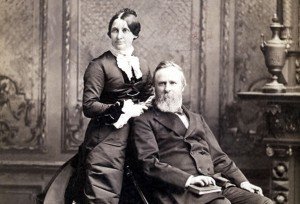

Image: President Benjamin Harrison

Image: President Benjamin Harrison

The First Lady was stunned to discover the press she generated whether at home or shopping in New York. She particularly resented the invasion of privacy resulting from press scrutiny of her family’s activities.

Although she detested the attention, some articles reported that she and her family actually courted and welcomed it, which prompted her to write toward the end of her tenure, “I have about come to the conclusion that political life is not the happiest – you are [so] battered around in it that life seems hardly worth living.”

The only real criticism Caroline ever received was for supposedly accepting a bribe – she accepted a cottage at Cape May Point in New Jersey from Postmaster General John Wannamaker. Caroline and the President were greatly troubled by the incident and paid Wannamaker $10,000 for the cottage to assuage the public outcry.

Late Years

In the winter of 1891-1892 while she tried to fulfill her social obligations, Caroline Harrison was frequently ill with bouts of bronchial infections. She was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which at the time had no known cure or treatment other than rest and good nutrition.

By the summer of 1892, she was very ill and depressed. Her illness and depression may have caused her to imagine that her husband was falling in love with her niece and secretary, Mary Lord Dimmick. A summer in the Adirondacks failed to restore her to health. In September the President brought Caroline home to the White House, where she lapsed into semi-consciousness.

Caroline Harrison died of tuberculosis at the White House on October 25, 1892, at age 60 – just before Benjamin Harrison lost his bid for reelection. Preliminary services were held in the East Room, after which her body was returned to Indianapolis for the final funeral at her church.

Daughter Mary Harrison McKee was already living at the White House with her family, and she took up the responsibilities of first lady for the last few months of Harrison’s term.

In 1896, Benjamin Harrison married his late wife’s niece and former secretary, widow Mary Scott Lord Dimmick, 33 years his junior. She survived him by nearly 47 years, dying in January 1948.

Legacy

Caroline Harrison’s legacy has proved to be historically important. The current architectural plan of the White House, complete with an East and West Wing, reflects the plan suggested by her in 1889, and the White House china room is certainly a testament to her historical sensitivity in rescuing, repairing and identifying artifacts from previous administrations. She was also greatly devoted to women’s rights, which brought more attention to that issue.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Caroline Harrison

First Lady Biography: Caroline Harrison

Whitehouse.gov: Caroline Lavinia Scott Harrison