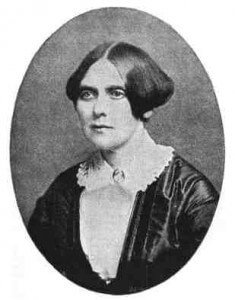

19th Century Abolitionists: Maria Chapman and Her Sisters

Maria Weston Chapman (1806-1885) was described by Lydia Maria Child as: “One of the most remarkable women of the age.” Chapman and three of her sisters played vital roles in the abolitionist movement. Maria, best-known of the group, and her sisters worked tirelessly in support of William Lloyd Garrison and his abolitionist paper, The Liberator. They founded an organization, circulated petitions, raised money, wrote and edited numerous publications, and left behind a remarkable correspondence.

Early Years

Maria Weston was born July 25, 1806, the eldest of eight children born in Weymouth, Massachusetts, to Warren and Nancy Bates Weston, who were descended from the Pilgrims. Maria and her siblings grew up on the family farm and attended local schools. Maria’s uncle, Joshua Bates, was a prosperous banker in London; he invited Maria to England to complete her education. When she returned to Boston in 1828, Ebenezer Bailey hired Maria as principal of his Young Ladies’ High School.

Marriage and Family

When she was 24, Maria Weston married Henry Grafton Chapman, son of a wealthy Boston merchant. Both soon began to work for the abolition of slavery. Unlike most businessmen, Maria’s father-in-law refused to participate in the lucrative cotton trade and supported a radical call for immediate abolition of slavery. Though Maria Chapman came to the anti-slavery cause through her husband, she quickly took up the cause.

Maria Chapman and Her Sisters

Maria was the only Weston sister to marry. Sisters Caroline and Anne were teachers in Boston; Deborah taught in New Bedford. Maria enlisted all three for her antislavery work. In 1834, Maria Chapman and her sisters Caroline, Anne, and Deborah Weston joined eight other women to form the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society – an abolitionist, interracial organization. As stated in the Society’s Constitution, these women founded the Society:

Believing slavery to be the direct violation of the law of God, and productive of a vast amount of misery and crime; and convinced that its abolition can only be effected by an acknowledgment of the justice and necessity of immediate emancipation – we hearby agree to form ourselves into a Society to aid and assist in this righteous cause as far as lies within our power. … Its funds shall be appropriated to the dissemination of TRUTH on the subject of slavery, and the improvement of the moral and intellectual character of the colored population. [They committed themselves to] sleep no more [now that the] long, dark night is rapidly receding, the light of truth has unsealed our eyes, and fallen upon our hearts, [and] awakened our slumbering energies.

Members of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society circulated petitions, raised money, wrote and edited publications, and corresponded with each other frequently. In her book Strained Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, Debra Gold Hansen states:

During its brief history [1834-1840] … it orchestrated three national women’s conventions, organized a multistate petition campaign, sued southerners who brought slaves into Boston, and sponsored elaborate, profitable fundraisers.

Boston Riot

Abolitionists, the most radical opponents of slavery, argued for the immediate emancipation of the slaves and establishment of racial equality. Although they were always a minority in New England, their numbers began to grow in the 1830s. Many Northerners believed that the campaign against slavery threatened their established institutions and expressed their opposition violently. Some Americans joined mobs; many others tolerated them, but an increasing number became outraged at the mobs and began supporting the right of the abolitionists to meet and speak.

In October 1835, British abolitionist George Thompson came to Boston to speak at a meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society at the office of William Lloyd Garrison’s publication The Liberator. An angry mob of businessmen who were involved in the cotton industry gathered outside the building. The mayor of Boston asked the women to leave, but Maria Chapman refused saying: “If this is the last bulwark of freedom, we may as well die here as anywhere.” Her protest was ignored and the women were escorted through the crowd and continued their meeting at the Chapman house nearby.

Members of the mob seized William Lloyd Garrison and dragged him through the streets of Boston at the end of a rope, presumably with the intent to hang him. The mayor rescued Garrison and held him overnight in the jail for his protection. The Boston Riot and similar incidents showed how deeply society was divided over the issue of slavery. Some newspapers justified the attack, while others criticized the mob. The Hampshire Gazette reported:

The riotous proceedings on Wednesday of last week in our literary emporium seem to require of the public press something more than a bare detail of facts. From the tone of most of the Boston papers, we should suppose that much credit was due to the mob for their gentlemanly conduct and dignified demeanor, rather than that a flagrant outrage upon personal liberty had been committed.

The moving cause of the rout was a notice given by certain ladies that the female abolition society would hold a meeting at their room in Washington Street. The Centinel says, it being expected that Thompson would address the meeting, a large body of respectable citizens assembled to prevent it… The Boston Gazette says that Garrison was protected by the four walls of prison “just in season to save him from a fate he well deserved, and which no one can contemplate without a shudder!” … All the Boston papers that we have seen attribute more blame to the abolitionists than to the ‘respectable’ mob, except the Courier and Post…

In defense of Garrison we do not now speak. Admitting him to be a hot-headed enthusiast, a notoriety hunter and all that his enemies represent him, it is enough to know, in order to condemn the conduct of the gentleman rioters, that he is an American citizen, and that there is no pretending that he has committed any offence against the laws of the land or morality… In the land of the free, in one of its most refined cities, in sight of the building where liberty was first cradled, in open and broad day, citizens calling themselves ‘respectable,’ to the number of five thousand, roused by the notice for a meeting of females, have assembled in riot, and hunted down… an innocent, terror-stricken man, whose greatest offence is, that he has used that liberty which God had given him, and which the constitution has guaranteed to him, in wrestling in behalf of the oppressed…

Away with this prating about the freedom and the equality of men, and constitutional principles, so long as three millions of people are held in fetters, and he who raises his voice for them with that liberty of speech wherewith the constitution has made him free, is hunted down like a wild beast, escapes death at the hands of an infuriated mob only by crawling for refuge into the cell of one who may have forfeited his life by crimes, and there thanks his Maker for the protection afforded him in the dank vapors of a dungeon.

In 1839, Maria Chapman, Lucretia Mott, and Lydia Maria Child were elected to the executive committee of the Anti-Slavery Society, which upset male members of the society. Lewis Tappan, the president of the society, argued: “To put a woman on the committee with men is contrary to the usages of civilized society.” However, members William Lloyd Garrison, Theodore Weld, Wendell Phillips, and Frederick Douglass were as committed to women’s rights as they were to the abolition of slavery.

An antislavery medallion from the late 18th century

The image of the kneeling slave appeared on handicraft goods such as quilts and purses sold at the antislavery fairs.

Throughout their public life, the Weston sisters continued to teach, while Maria ran a busy household which became a center for abolitionist activities. The Chapmans frequently entertained fellow abolitionists, including “coloured” guests, and housed out-of-town delegates who came to attend meetings in Boston.

Boston Anti-Slavery Fair

In 1835, Chapman assumed the leadership of the Boston Anti-Slavery Fair, the chief fundraising instrument of the American Anti-Slavery Society. For the next 23 years, Maria and her sister Anne Weston were chief organizers of the fairs. These became popular Boston social events. By the third year it had grown so big it had to be held at the Artist’s Gallery Hall. From January on, women knitted and sewed goods to sell, and abolitionist societies around the state competed to contribute the most items. By 1838, the fair raised more than $1,000 and by 1840 it was so big it had to be held in Faneuil Hall.

The 15th National Anti-Slavery Bazaar was advertised in William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator:

The variety, beauty and elegance of the exhibition will be far greater than any former year, owing to increased exertions of members of the committee now in Europe, and to the generous donations of friends of the Cause, both at home and abroad.

From 1839 to 1858, Chapman also edited the Society’s annual publication, The Liberty Bell, which was modeled on the gift books that were popular at the time. She pressed her sisters into the work as well as soliciting contributions from such notables as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Eliza Cabot Follen, Wendell Phillips, Harriet Martineau, and James Russell Lowell.

Chapman also contributed to numerous other antislavery periodicals during those years. She edited The Liberator in Garrison’s absence, and was on the editorial committee of the National Anti-Slavery Standard, the official mouthpiece of the AAS, and was a member of the peace organization, the Non-Resistance Society, which published The Non-Resistant.

Three daughters and a son had been born to the Chapmans between 1831 and 1840. The youngest daughter died of tuberculosis, which also afflicted her father. A trip to the West Indies failed to restore his health. Henry Grafton Chapman died of tuberculosis October 3, 1842 at the age of thirty-eight. As Henry had requested, Wendell Phillips became guardian of the Chapman children.

In 1848 Maria took the Chapman children to Europe to continue their education. Her sister Caroline joined them. In the following fall, Henry Jr. enrolled in school in Heidelberg, Germany; his sisters attended an academy in Paris, where Maria and Caroline quickly found sympathizers for American anti-slavery movement. Maria also recruited French contributors to the Liberty Bell. She and Caroline shipped items to sister Anne in Boston to sell at the antislavery fairs.

During visits to England, Maria forged a friendship with British writer Harriet Martineau, whom she had met in Boston in 1835. Martineau asked her American friend to edit her memoirs, which were published in 1877 as The Autobiography of Harriet Martineau with Memorials by Maria Weston Chapman.

By the time Henry Jr. had completed his education, his sister Elizabeth had married a French abolitionist, and the other Weston sisters had joined the group in Paris.

In 1855 Maria returned to Weymouth, Massachusetts, where she lived for the rest of her life. During extended visits to her son in New York City, she worked in his brokerage office. When the American Civil War began, the Weston sisters joined her in Weymouth.

Oil painting by William Tolman Carlton depicts slaves waiting for the Emancipation Proclamation to take effect. The original hangs in the White House, in the room where President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

After President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Maria and Garrison closed down the anti-slavery organizations. Maria Chapman and her sisters retired from public life. Maria devoted her time to educating the former slaves.

Maria Chapman died July 12, 1885 of heart disease at at age seventy-eight. By 1890 all the Weston sisters were buried in the Weymouth family plot.

Maria Chapman Published Works

Songs of the Free and Hymns of Christian Freedom (1836), first U.S. antislavery song-book

Right and Wrong in Massachusetts (1839)

Ten Years of Experience (1842).

Trial and Imprisonment of Jonathan Walker, at Pensacola, Florida, for Aiding Slaves to Escape from Bondage (1846).

How Can I Help to Abolish Slavery? (1855).

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Maria Weston Chapman

African American Registry: Marie Chapman

Newspaper Article: The Boston Riot of 1835

Maria Weston Chapman and the Weston Sisters

Maria Chapman and Her Sisters Fight With Fairs Against Slavery

Society for the Study of American Women Writers: BFASS Constitution