Wife of Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Fanny Longfellow (1817-1861), wife of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, was a skilled artist and was well-read in many subjects. Fanny’s father Nathan Appleton gave Craigie House to the Longfellows as a wedding gift, and it became a meeting place for literary and philosophical figures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Julia Ward Howe. During their happy marriage, Fanny gave birth to six children (two boys and four girls).

Fanny Longfellow (1817-1861), wife of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, was a skilled artist and was well-read in many subjects. Fanny’s father Nathan Appleton gave Craigie House to the Longfellows as a wedding gift, and it became a meeting place for literary and philosophical figures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Julia Ward Howe. During their happy marriage, Fanny gave birth to six children (two boys and four girls).

Image: This portrait of Fanny was done by Samuel Rowse in 1859. It hangs over the fireplace in the Gold Ring Room, Longfellow’s bedroom at Craigie House in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as it did when he was alive.

Childhood and Early Years

(Frances) Fanny Appleton was born on October 6, 1817, in Boston, Massachusetts, daughter of Nathan and Maria Theresa Gold Appleton of Boston’s fashionable Beacon Hill. Her father was a prosperous banker, manufacturer and congressman who was among the founders of the city of Lowell, Massachusetts, and was a leader in the Industrial Revolution. Her mother died when Fanny was fifteen.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born on February 27, 1807, in Portland, Maine, to Stephen and Zilpah Longfellow. The family soon moved to a house on Congress Street, now known as the Wadsworth Longfellow Home. Early on young Henry knew he wanted to be a poet; he was a fast learner and loved to write, publishing his first poem at age 13 in The Portland Gazette. At 15 entered Bowdoin College, where his classmates included Nathaniel Hawthorne and Franklin Pierce.

The Bowdoin trustees offered Longfellow a professorship in Modern Languages when he graduated in 1825. He studied in France, Spain, Italy and Germany to prepare for this new position, then returned to Bowdoin where he spent six years teaching, publishing textbooks and writing articles for popular literary reviews.

In 1831, Longfellow married Mary Storer Potter, a Portland neighbor and friend of his sister Anne. The two lived in Maine until Longfellow was offered a position as head of the Modern Language Department at Harvard College in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Once again, he traveled to Europe to study. Mary became ill and died after having a miscarriage while they were in Rotterdam, Netherlands, in November 1835.

Suffering from grief, Longfellow plunged into study and spent the following winter and spring in Heidelberg perfecting his German. Henry met the Appletons eight months after Mary died, while summering in Switzerland. Fanny Appleton captivated Longfellow, but she did not show the same interest in him.

The young professor left soon after for America and his duties at Harvard. Longfellow persuaded Elizabeth Craigie to accept him as a boarder at her home overlooking the Charles River in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His first writings were published during these years. Hyperion, an autobiographical novel (a thinly veiled account of Longfellow’s love for and rejection by Fanny Appleton), appeared in 1839, then A Romance and Voices of the Night.

Resuming his friendship with Fanny Appleton, Longfellow was crushed by her rejection of his marriage proposal in 1837, but he was determined to win Fanny’s heart. In July 1839, he wrote to a friend: “[V]ictory hangs doubtful. The lady says she will not! I say she shall! It is not pride, but the madness of passion”. His friend George Stillman Hillard encouraged Longfellow in the pursuit: “I delight to see you keeping up so stout a heart for the resolve to conquer is half the battle in love as well as war.”

During the courtship, Longfellow frequently walked from Cambridge to the Appleton home in Beacon Hill in Boston by crossing the Boston Bridge. That bridge was replaced in 1906 by a new bridge which was later renamed the Longfellow Bridge.

After seven years of courtship, Fanny married Longfellow on July 13, 1843. Her father purchased the Craigie House later that year and presented it and the surrounding grounds to the Longfellows as a wedding gift. Well-educated, Fanny was a perceptive critic of art and literature who happily shared her husband’s pursuits. Henry and Fanny were seldom apart.

The home, well-known even then as George Washington‘s headquarters during the early days of the American Revolution, would be their residence for the rest of their lives. Fanny never changed the room where George and Martha had celebrated their 17th wedding anniversary amid the sorrows and uncertainties of war.

The family home was a favorite gathering place for artists, philosophers, writers and reformers, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Julia Ward Howe, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Charles Dickens and Charles Sumner. An active abolitionist, Longfellow contributed money to help freedom-seeking and former slaves and to support the anti-slavery cause.

The Longfellows were blessed with the birth of six children – Charles (1844), Ernest (1845), Fanny (1847, who died in childhood), Alice (1850), Edith (1853) and Allegra (1855). Alice was delivered while her mother was under the anesthetic influence of ether – the first time it was used in North America.

Fanny was a skilled artist, art collector and insightful commentator on 19th-Century Boston literary culture, well-travelled, and well-read in many subjects. She was a loving and attentive mother and had much influence on the intellectual growth of the Longfellow children. At Craigie House they formed the warm family circle that became a kind of national symbol for domestic love, the innocence of childhood and the pleasure of material comfort.

By 1854 Longfellow was able to resign from Harvard. He had become, at age forty-seven, one of America’s first self-sustaining authors. For the next seven years, Henry was able to pour his energies into his writing, unimpeded by teaching duties and supported by the love of his family. Evangeline, The Song of Hiawatha and The Courtship of Miles Standish – all published between 1847 and 1858 – brought him great popularity and fame.

On July 9, 1861, Fanny recorded in her journal:

We are all sighing for the good sea breeze instead of this stifling land one filled with dust. Poor Allegra is very droopy with heat, and Edie has to get her hair in a net to free her neck from the weight.

The following day, after trimming some of seven year old Edith’s beautiful curls, Fanny decided to preserve the clippings in an envelope. While she was melting a bar of sealing wax with a candle to seal the keepsake in the envelope, a few drops fell unnoticed in her lap. A breeze came through the window, igniting Fanny’s dress – immediately wrapping her in flames.

In her attempt to protect Edith and Allegra, Fanny ran to Henry’s study in the next room, where Henry frantically attempted to extinguish the flames with a throw rug. Failing to stop the fire with the rug, he tried to smother the flames by throwing his arms around Frances – severely burning his face, arms and hands.

Fanny Longfellow died of her injuries the next morning, July 11, 1861, at the age of 43, and was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge.

Too ill from his burns and grief, Henry did not attend her funeral. His facial scars and the difficulty of shaving caused him to grow the beard that gave him the sage and distinguished look reproduced in so many paintings and photographs.

A month after Fanny’s death, on August 18, 1861, Longfellow wrote about his despair in a letter to his late wife’s sister, Mary Appleton Mackintosh:

How I am alive after what my eyes have seen, I know not. I am at least patient, if not resigned; and thank God hourly – as I have from the beginning – for the beautiful life we led together, and that I loved her more and more to the end.

Longfellow continued to reside in the house they had shared and served as both father and mother to the children. The first Christmas after Fanny’s death, he wrote, “How inexpressibly sad are all holidays.” The entry for December 25, 1862 reads: “A merry Christmas’ say the children, but that is no more for me.” The Christmas of 1863 was blank in his journal.

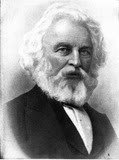

Image: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The Civil War years brought such popular and esteemed works as Tales of the Wayside Inn with its Paul Revere’s Ride in 1863. Clever marketing, often initiated by the poet himself, expanded the audience for all these works until Longfellow had become one of the best selling and most widely read authors in the world.

In 1863, Longfellow’s son Charley ran off to fight in the Civil War. Charley knew his father disapproved, but went anyway. He wrote a letter to his father saying, “I have tried to resist the temptation of going without your leave but cannot any longer.” Twice during the war Henry was called to Washington to care for his son – once because of illness and once due to severe injury. Charley survived the war and spent much of his adult life traveling the world.

Longfellow’s three daughters also appeared on the field of battle: shortly after the fighting ended at the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, a copy of a Thomas Buchanan Read painting of Edith, Alice and Allegra was found. The identity of its owner has never been discovered. It was not found on or close to any soldier’s body, so no one knows who was carrying it.

On Christmas Day of 1864, Longfellow wrote the words of the poem, Christmas Bells. The reelection of Abraham Lincoln or the possible end of the terrible war may have been the occasion for the poem, which reflected the prior years of the war’s despair, while ending with a confident hope of peace. Music was added to the poem and it became the Christmas carol we know now as I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day.

The greatest part of Longfellow’s creative energy for several years thereafter went into the translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy, one of the great monuments of world literature, and a prolonged meditation on the spiritual power of love to overcome death. It was published in 1867. Though he continued to write fine verse, what were to be Longfellow’s most famous works were done, but his fame continued to grow. Honors of every kind were bestowed on him in Europe and America.

Longfellow never fully recovered from Fanny’s death. The strength of his grief is still evident in these lines from a sonnet he wrote eighteen years later, The Cross of Snow (1879):

There is a mountain in the distant West

That, sun-defying, in its deep ravines

Displays a cross of snow upon its side.

Such is the cross I wear upon my breast

These eighteen years, through all the changing scenes

And seasons, changeless since the day she died.

Also in 1879, it became necessary to remove “the spreading chestnut tree” Longfellow had immortalized in his poem The Village Blacksmith. The children of Cambridge gave their pennies to build a chair out of the tree and gave it to Longfellow. It was a gesture returning to the poet a bit of the love he had given to his own and other children.

Longfellow became very quiet, reserved and private in later years; he was known for being unsocial and avoided leaving home. However, he was such an admired figure in the United States during his life that the public celebration of his 70th birthday in 1877 took on the air of a national holiday, with parades, speeches and the reading of his poetry.

In March 1882, the revered poet went to bed with severe stomach pain, and endured the pain for several days with the help of opium.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow died surrounded by family on March 24, 1882, a month after his 75th birthday, in the same bed where Fanny’s life had ended 21 years before. He had been suffering from peritonitis. He is buried with both of his wives at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. At the time of his death, his estate was worth an estimated $356,320.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was a commanding figure in the cultural life of nineteenth-century America. His poetry is based on familiar themes with simple, clear and flowing language. Often an unusual mix of despair and encouragement, his work struck a responsive chord in the nation’s heart and mind, and was touted as the people’s poet. Longfellow is one of those great men who leave a legacy that informs the coming generations why they were called ‘great.’ We have too few of those.

SOURCES

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Wikipedia: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The Literature Network: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow