First Female Mexican American Author to Write in English

Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton is among the best remembered authors of nineteenth-century Mexican American literature. Fully bilingual, de Burton was the first female Mexican American to write novels in English: Who Would Have Thought It? and The Squatter and the Don.

Early Years

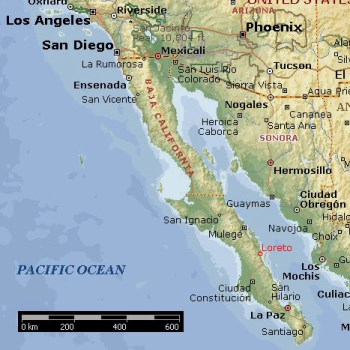

Though records are sparse, Maria Amparo Ruiz was born into an aristocratic Latino family in Loreto on the Baja California peninsula of Mexico. Her grandfather, Don Jose Manuel Ruiz, was sent to the frontier to assist in the founding of missions in Baja.

Heading a large force of men, Ruiz left Loreto in 1780, and several missions were soon founded. For this, Ruiz was awarded a large grant of land, “…48,884 acres was conferred upon Lieutenant Jose Manuel Ruiz of the Spanish Army, July 10, 1804 for gallant services.” As granddaughter of Ruiz, Maria would one day inherit the vast Rancho Ensenada de Todos Santos established on those lands by her grandfather.

As residents of Baja California for many years, Maria’s family became closely intertwined with the major events and problems of the era. The family’s control of the area came to an end during the Mexican-American War (1845-48), when the American army occupied Baja and forced the surrender of its citizens.

At age fifteen, Maria witnessed the surrender of La Paz in 1848 to American troops. This event would alter the course of her life forever, for during the incident, Maria met Captain Henry Stanton Burton, a U.S. army officer from New England who was sent to Lower California to take control of La Paz.

Beautiful, articulate, well-educated and charming, Maria Amparo Ruiz captivated Burton and they soon began a romantic relationship. He personally arranged for transportation to Monterey on the war transport Lexington for Maria, her mother and brother. At the close of the war, she took advantage of the terms of the Treaty of Guadelupe-Hidalgo to move to Alta California with her mother, where the two became American citizens.

The young soldier and his lovely senorita soon found their romance fraught with difficulties. The greatest barrier to marriage was religious. Burton was a Protestant and too much of a national figure to publicly change his religion. Maria, as the daughter of a well known Spanish Catholic family, could hardly be expected to change hers.

Marriage and Family

Maria Ruiz and Henry Burton overcame all obstacles placed in their path and were married on July 7, 1849 by a Protestant minister at the home of General E.R.S. Canby in Monterey, California. Canby was subsequently forced to explain to his superiors his part in the proceedings. Without Canby’s knowledge, the marriage was performed at the invitation of his wife, Louisa Hawkins Canby “who, with nearly all of the Protestants then residing at Monterey, was present at the ceremony.”

Embarking on a new life within a social circle made up of both native Latino Californio landholders and Anglos, Maria soon mastered the English language and gained a reputation for her beauty and her air of aristocracy. Burton was sent to take charge of the Army post at Mission San Diego de Alcala in 1852. The Burtons then returned to San Diego.

On March 3, 1854, the Burtons homesteaded a large parcel of land near San Diego known as Rancho Jamul, a total of 562,622 acres. The Burtons settled in an adobe on the slopes with their small daughter, Nellie, along with Maria’s mother and brother. Their son Henry was born on the ranch; he was named for Burton’s associate in the takeover of La Paz, General Henry Halleck. Maria wrote of her aspirations:

…I am persuaded that we were born to do something more than simply live, that is, we were born for something more, for the rest of our poor countrymen.

In 1859, Colonel Burton was ordered east, taking the family with him. Maria’s mother and brother were left behind to maintain the Jamul property, an important consideration in this era of squatters and unscrupulous land deals. The night before the Burtons left, a large ball was held by the people of San Diego to express their thanks for the interest of the Burtons in the progress of their city.

On August 2, 1859, the Burtons left for Fort Monroe, Virginia on a steamer via the Isthmus of Panama. Life in the East would be just as busy as it had been in Califor-nia. Henry Burton was soon promoted, first to major and then to brigadier general in the Union Army. His position in the army enabled Maria to circulate in elite East Coast society and to see the inner workings of U.S. political and military life first-hand.

On one of their trips to Washington, DC, they attended the inauguration of President Abraham Lincoln in March 1861. Maria made an intriguing comment regarding the inauguration in one of her letters:

Well, the inauguration of Mr. Lincoln has passed without problem and he has given his first public reception without having been assassinated as was expected… The state of the country continues in agitation and the danger of war is ever present.

While in Washington, Maria attended numerous balls, receptions and social activities. Always a social asset, the charming and beautiful young wife of an important officer delighted Washington society. As the wife of an American military officer, she traveled widely among the Eastern states as her husband was transferred from post to post.

On March 13, 1865, Henry was made a Brevet General “for Gallant and Meritorious Services” during the capture of Petersburg, Virginia. While erecting the works around Petersburg, Henry contracted malarial fever and became seriously ill. Recurrent attacks would plague him for the next four years. It became necessary at times for him to be relieved of duty.

On April 4, 1869, Henry Burton died of apoplexy (stroke) in Newport, Rhode Island, no doubt brought on by the malaria attacks, leaving Maria a thirty-seven-year-old widow with two children.

Widowhood and Legal Battles

After Henry’s burial at West Point, Maria returned to Rancho Jamul to rebuild her life. She soon discovered that her claim to Rancho Jamul was questionable and her claim to the Rancho Ensenada de Todos Santos in Baja was in jeopardy. These two circumstances would embroil her in endless litigation that would cease only with her death.

The pastoral lifestyle of the great ranchos was giving way under the ever increasing demands of the incoming Americans who were eager for land, power and money. Legislation was passed which often favored unscrupulous newcomers. This had far-reaching effects as Hispanic families bowed to the various pressures facing them and their lands passed into American hands.

Maria was determined not to lose her lands without a fight. For the next twenty-three years of her life she fought numerous legal battles, with more losses than wins. She hired the best attorneys possible and pulled strings in high places to help her claims. Her major fight was over Rancho Jamul which she claimed as the widow of Henry Burton, homesteader of the land, but Burton had died intestate, thereby creating enormous problems for Maria.

Despite all the furor, Maria continued making a variety of plans for the rancho. She ran cattle, as well as growing wheat and barley on the slopes. Castor beans were also raised, bringing sixty dollars an acre in 1874. The cattle were fed with the leaves and the beans were sold to a paint company. Even the hillsides covered with wildflowers were rented for beehives.

Always very active and resourceful, Maria traveled to Washington to see if she could strengthen her claim. While there she lobbied a special act through Congress to help her cause. On October 26, 1876, a land patent was issued to Maria, her daughter Nellie and son Henry for 8,926.22 acres. Their success was short-lived as numerous claims were filed against the estate and the litigation continued for years to come.

Maria’s claim to her grandfather’s land in Baja California was not settled either. The Baja land was valuable primarily for the port of Ensenada. Its proximity to the mines in San Rafael gave it added value. Always a shrewd businesswoman, Maria owned warehouses in the city of Ensenada.

Literary Career

Despite her financial and legal entanglements, Ruiz de Burton found time to launch a literary career in the 1870s, publishing two novels for an English-speaking audience. Both books critique the dominant Anglo society and express her resentment over the discrimination and racism experienced by many Latinos residing in the United States.

Her first novel, Who Would Have Thought It? (1872) denounces what she viewed as the hypocritical sanctimoniousness of New England culture. It was published anonymously, probably because its biting satire of Congregationalist religion, of abolitionism, and even of President Lincoln made it controversial. She also wrote a play: Don Quixote de la Mancha: A Comedy in Five Acts: Taken From Cervantes’ Novel of That Name (1876).

In 1885, Ruiz de Burton published her second novel The Squatter and the Don, a fictional account of the land struggles experienced by many Californio families after U.S. annexation. The book is a historical novel which chronicles the demise of the feudal Spanish rancho system in California, and questions whether the imposition of American monopoly capitalism is an improvement over the old way of life.

Late Years

Though Ruiz de Burton had finally received clear title to the Baja land in 1871, in 1883 the Mexican Law of Colonization allowed foreign development and this created major problems for Maria. A land developing firm, claimed eighteen million acres in the Partido Norte and encroached on the Rancho Ensenada. This confrontation would drain her resources and take her to the highest courts of Mexico City.

Even the San Diego Union felt compelled to voice its opinion on the Ensenada issue. Maria’s claims were investigated by the top lawyers of Mexico City at the request of the Union and were found to be wanting. The furor continued to grow. Maria put a notice in the Union, warning prospective purchasers of land from the International Company that the title was not clear.

Ruiz de Burton was finally given most of the land she claimed in 1889. When things were somewhat settled and it appeared Maria had won, her mother, Isabel Ruiz Maytorena, sued her, claiming she had been defrauded of her land. Speaking no English, she signed a paper she believed gave power of attorney to Maria. Later she found she had signed a paper transferring her claim to the land grant over to Maria. This further added to the complexities of the case.

There were some bright spots in these years of turmoil and stress. Maria’s daughter Nellie married Miguel de Pedrorena, member of a leading San Diego family, on Christmas Day 1875 at the Horton House in San Diego. It was a grand affair and a happy event as the young couple was very popular in the community. Maria’s son Henry married Minnie Wilbur at Rancho Jamul and settled there with his bride to help his mother run the ranch.

Suits and countersuits continued to plague Maria’s life. Her claim to Rancho Ensenada was reversed by the Supreme Court of Mexico. As a result of the various claims filed against it and the incursions of over one hundred sixty squatters, Rancho Jamul was divided. Maria received only a small portion of the original claim.

Image: Map of Baja California, Mexico

Maria Ruiz de Burton died August 12, 1895 of gastric fever in Chicago, while she was trying to raise money and political support for her claim to the Baja California land. Her body was returned to San Diego for burial.

Maria’s death closed a colorful chapter in California’s history. Land problems were a major source of tension for both American and Hispanic populations. The transition from cattle ranches to agriculture was pushed by a severe drought in the 1860s and the Fence Laws of 1864. Lands were often lost because of lack of documents proving ownership. Sometimes lands had to be sold in order to pay for legal services.

SOURCES

Maria Ruiz de Burton

Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton

San Diego History: Maria Amparo Ruiz Burton