The Slave Insurrection of New York City

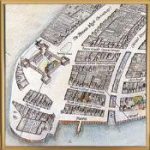

Image: John Hughson’s Tavern

The tavern was on the waterfront in 1741 and its doors were open to blacks and poor whites, and it had a bad reputation among the respectable citizens of New York City.

Thirteen black men burned to death at the stake. Seventeen black men hanged. Two white men and two white women also hanged. All thirty-four were executed in New York City between May 11 and August 29, 1741, as part of the episode early New Yorkers called the “Great Negro Plot” or the “New York Conspiracy.”

~Thomas J. Davis, A Rumor of Revolt

In 1741, New York was still a town on the lower end of Manhattan Island, with a population of about 12,000; more than 2000 were slaves. Rumors of slave uprisings were everywhere, and to compound the problem, the winter of 1740–41 was especially severe. Bread was scarce and expensive, and the poor – black and white – were in a miserable state.

In the spring and summer of 1741, New York City’s white residents panicked over what they saw as an imminent slave insurrection. They still remembered the slave insurrection in 1712 that involved arson and the murder of nine whites that resulted in the execution of 19 black slaves. At the time, one out of every five residents of the city was a black slave. There were laws that restricted slave activities, but they were poorly enforced.

On a late February night, there had been a burglary at the Broad Street shop of merchant Robert Hogg. Taken were a pair of silver candlesticks, some linen, and a sack of silver coins. Arrested the next day and charged with the crime was a black slave named Caesar.

When Caesar was arrested he was with his mistress, a white prostitute named Peggy Kerry, at Hughson’s Tavern, which had a bad reputation. Like other taverns in the port, it had become a gathering place for blacks, sailors, prostitutes and other types whom the townspeople considered unsavory.

Hughson and his wife, Sarah, both white, were under suspicion. Their 16-year-old white indentured servant Mary Burton accused the Hughsons of receiving stolen property from the slaves. Hughson was confronted with these accusations and denied them, attacking Mary Burton as a good-for-nothing who was simply trying to make trouble for her master.

On March 18, 1741, the first of a series of suspicious fires broke out in the city, and whipped by a strong wind, swept through Fort George on the Battery. It started in the roof of the residence of Lieutenant Governor George Clark, who headed the colonial administration.

New York’s first firefighters, with the aid of all the citizens who had heard the alarm, ran with the two engines down to the fort. But the gale fanned the blaze beyond their control and many of the citizens, fearing gunpowder explosions, fled from the fort. The official residence burned to the ground and the flames spread to the chapel, the secretary’s office, and the barracks, until everything within the walls of the fort was in ashes.

Suspicions grew that black slaves were responsible. Four fires were set on April 6. Mobs of angry white citizens roamed the streets to round up black slaves, and nearly a hundred were hauled off to jail. Authorities convicted Caesar and another slave, and on May 11 they were hanged. Two more slaves were hanged on May 30, but not before they had accused dozens of others of being in on a conspiracy to burn New York.

Mary Burton told a grand jury that the Hughsons, Peggy Kerry, Caesar, and other slaves had plotted to burn the city and massacre the whites. The Hughsons and Kerry were tried on June 4 and found guilty. Still protesting innocence of any conspiracy, they were hanged within a week, and John Hughson’s body was displayed in chains.

Mary Burton spun wilder and wilder stories. As the trials progressed judges and jurors seemed to take everything she said with utter seriousness, and her accusations began to broaden in scope. A number of whites as well as blacks were then incriminated and questioned. When pardons were promised to all who confessed by July 1, the accused named more people, who then blamed others.

One of the alleged conspirators was a slave from Brooklyn named Doctor Harry, who was accused of bringing poison to Hughson’s tavern for blacks to use to commit suicide if they were convicted. He denied ever being at Hughson’s, but was burned alive at the stake on July 18.

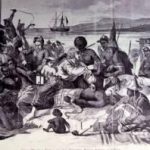

Image: Slave Burned Alive at the Stake

One of the trial judges later described the scene in his book: “About three o’clock the criminals were brought to the stake, surrounded with piles of wood ready for setting fire to, which the people were very impatient to have done, their resentment being raised to the utmost pitch against them, and no wonder.”

In the meantime, the suspicious fires had stopped. Believing that the conspiracy had run its course, New Yorkers breathed a sigh of relief, and the wave of incriminations began to subside. It seemed as though the trials had run their course and that the panic was over.

But on the last day of August, the fear, anger, and suspicion resulted in the hanging of a white schoolteacher, John Ury. He was officially found guilty of conspiracy, but he was tried because he was thought to be a Catholic priest, which he wasn’t. Catholics were often discriminated against in the strongly Protestant city. Ury was the last man executed as a result of the presumed conspiracy.

Some blacks continued to be arrested, but the panic was over, and New York began to return to normal. With the lessening of fear came a reaction to the trials themselves. Some prominent citizens, especially those who had lost slaves, became openly critical and put pressure on authorities to halt the trials. The proceedings came to an end.

Seemingly untroubled by pangs of conscience, Mary Burton claimed the 100 pound reward that had been offered “to any white person that should discover any person or persons concerned in setting fire to any dwelling houses, store-houses, or other buildings within this city…”

Mary Burton got the reward, plus a note from the New York council thanking her “for the great service she has done.” She took her money and disappeared from the province of New York.

The American Revolution (1775-1783) further concentrated slaves in Manhattan. The city remained in the hands of the King’s forces until their withdrawal in 1783, and loyal slaveholders fled there with as many slaves as they could muster. At the end of the war, they sailed away with their slaves.

In 1790 when the new United States took its first federal census, it numbered 2369 slaves in New York City and 21,324 in the state, a number that ranked it fifth among states, even ahead of Georgia.

SOURCES

The Negro Plot Trials

New York Conspiracy of 1741

Slave Island – New York’s Hidden History