First Female War Correspondent in the U.S.

Jane McManus (1807–1878) was a single mother and journalist, an adventurer and the first female war correspondent in American history. Whether she was land speculating in Texas, behind enemy lines during the Mexican American War, filibustering for Cuba or Nicaragua or urging free blacks to emigrate to the Dominican Republic, McManus seldom took the easy path.

No matter what name or pseudonym she was using at the time, Jane Eliza McManus Storm Cazneau was one of the most formidable women of the 19th century. She foresaw a nation with equal rights for all, in a world in which representative government was the norm rather than the exception. She was not just an advocate of Manifest Destiny, she fought for it with her pen and her life.

Childhood and Early Years

Jane Maria Eliza McManus was born on April 6, 1807 in the town of Brunswick near Troy, New York, the daughter of Congressman William McManus and Catharine (Coons) McManus. She attended Emma Willard‘s Troy Female Seminary, one of the earliest colleges for women, but did not graduate.

On August 22, 1825, at the age of eighteen, Jane married Allen Storm, a student in her father’s law office, and in 1826 she gave birth to a son, William McManus Storm. By 1832, however, the marriage had failed and Jane had resumed her maiden name.

In Texas

Jane McManus was first introduced to the potential of Texas, then part of the Mexico, when her father became involved with his friend, former U.S. Vice President Aaron Burr, in the Galveston Bay and Texas Land Company in 1832. Jane kept the books for the Company in New York and before long was visiting Aaron Burr, fifty years her senior, at his law office in Jersey City. She was widely said to be Burr’s mistress and was cited in his divorce in 1835.

Late in 1832, Jane and her brother Robert traveled to Texas, which was then still part of Mexico, and acquired rights to two enormous tracts, one on the Gulf of Mexico and the other near the present site of Waco, Texas. Jane was to use part of this land to Jane to bring families to settle there as part of Stephen F. Austin’s colony – the first legal settlement of North American families in Texas.

Led by the Empresario Stephen F. Austin, an initial grant for three hundred families in 1821 opened up Texas to a flood of American immigrants, as many as 30,000 by the time of the Texas Revolution in 1835. An empresario was a person who, in the early years of the settlement of Texas, had been granted the right to settle on Mexican land in exchange for recruiting and taking responsibility for new settlers.

The settlement of Austin’s colony from 1821 to 1836 brought Anglo and African settlers from the United States. Many of the historical events of Southeast Texas owe their origin to this colony. In 1833, Jane and several hundred German settlers set out to take possession of the land she had purchased, but her plans failed when the Germans refused to go beyond Matagorda.

Jane McManus returned home with her father to Brunswick, New York, but her brother Robert remained in Texas and eventually became a wealthy planter. Jane pledged money to the Texas Independence movement, and in the 1840s she advocated the annexation of Texas in her newspaper columns. Intermittent conflicts between the two nations were finally resolved with the Mexican-American War of 1846 to 1848 after the annexation of Texas to the United States.

Her early adventures in Texas left McManus with two lifelong assets: she became fluent in Spanish and she acquired a set of contacts with many powerful people on the frontier including the founders of the Republic of Texas, among them Sam Houston and his successor, Jane’s partner in a lively exchange of letters, Mirabeau Bonaparte Lamar.

Career in Journalism

Back in the U.S. in 1839, Jane McManus turned to journalism as a career. Her first journalistic assignment came from New Yorker editor Horace Greeley, who hired her to travel to the Mediterranean and the Ottoman empire. She visited Smyrna, Aleppo, Tangier and Cadiz. She also wroite for Moses Yale Beach’s New York Sun and John O’Sullivan’s Democratic Review.

It was not common for women to write for the newspapers in the mid-nineteenth century, and almost unprecedented for them to do so in as confident and aggressive a tone as did Jane McManus. As a journalist, an advisor to national political figures and publicist, McManus helped shape United States domestic and foreign policy from the mid–1840s through the 1870s.

She strongly advocated Manifest Destiny: the belief widely held in the 19th century that the United States was destined to expand across the entire continent of North America. The belief in an American mission to promote and defend democracy throughout the world was later expounded by Abraham Lincoln. But Manifest Destiny never became a national priority in the 1840s. By 1843, John Quincy Adams, a major supporter, had changed his mind and repudiated Manifest Destiny because it meant the expansion of slavery in Texas.

McManus was in tune with the Young America Movement, a political and cultural attitude in the mid-nineteenth century. Inspired by European reform movements of the 1830s (such as Young Italy), it advocated free trade, social reform, expansion southward into the territories and support for republican movements abroad. Senator Stephen A. Douglas promoted its nationalistic program in an unsuccessful effort to compromise sectional differences.

With the outbreak of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), McManus went to the front, where she witnessed Winfield Scott’s capture of the fortress of Vera Cruz in March 1847 as the first female war correspondent in American history. McManus also played an unofficial role in Moses Yale Beach’s peace mission to Mexico City, and began to promote the “All Mexico” movement, which argued for the annexation of Mexico to the U.S. in order to establish peace.

In January 1848, McManus accepted the position of editor of La Verdad (Spanish for Truth) a weekly paper published in New York and financed by wealthy Cuban liberal exiles. But a romantic plan to turn Cuba into an independent republic that could later be annexed like Texas eventually failed.

A single parent and working mother, McManus was not a women’s rights advocate who agitated for suffrage. She ridiculed the Seneca Falls housewives’ complaints because real oppression existed for women in the factories, in the needle trades, on Indian reservations and in the Caribbean. She advised working women to educate themselves and take better-paying men’s clerical jobs.

In 1849 at the age of forty-two, Jane McManus married an old friend, General William Cazneau. They had met in Texas and both shared a romantic vision of American expansion, and an ambition to make a fortune out of land speculation. McManus moved in 1850 to a town Cazneau helped to establish: Eagle Pass, Texas – a frontier village three hundred miles up the Rio Grande from the Gulf of Mexico.

As Cazneau travelled ceaselessly chasing one scheme after another, Jane settled down at Eagle Pass. In the book she wrote about her life there, she described the life of an Old Testament matriarch with her flocks and herds. She got to know Native American chiefs with names like Crazy Bear, Gopher John and Wild Cat, whose interpreter was an African American called John Horse. Life on the frontier had its idyllic moments for Jane as she rode her black pony, Chino, but she recognized the hardships and dangers for frontier women as well.

In the Caribbean

William Cazneau was appointed American diplomatic agent to the Dominican Republic by President James Buchanan, and Cazneau and McManus moved there in 1855. General Cazneau’s job was to report events, and he also lobbied for an American coaling station and port at Santana Bay. From then until their deaths, with the exception of one short interval, they lived on an estate there named Esmeralda.

For a time they moved, in spite of Jane’s hostility to all things British, to a beautiful estate in Jamaica, Keith Hall, where she continued, in spite of failing eyesight, to write up-beat accounts of life in the tropics. Despite her earlier sympathies for southern expansionism McManus disapproved of secession, and during the Civil War she was hired by William Seward, President Lincoln’s Secretary of State, to write propaganda against the Confederacy.

Seward and McManus were both expansionists who feared that the war would weaken the United States and prevent further American thrusts into the Caribbean. After two years in Jamaica, McManus and Cazneau returned to the Dominican Republic and aided Presidents Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant in their attempts to acquire land in the country.

Jane McManus Storm Cazneau’s two dreams were both only partly successful. In an attempt to make a great fortune in land speculation, she and her husband did invest in Texas land, and in real estate and mines in the Dominican Republic, Jamaica and Nicaragua, with varying degrees of success.

Her second dream was much more difficult to attain. It involved her passionate belief that America’s destiny was to bring the benefits of freedom to the whole of North America, and to Central America and the Caribbean as well. She was a vigorous champion of American annexation, especially of Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua.

Yet she had a remarkable degree of influence on the mid-nineteenth-century course of American foreign policy. It came from her ability to impress powerful men – from Burr and Houston to Beach, Polk and Seward – with her romantic vision of America’s ‘manifest destiny’ to bring freedom to the Spanish-speaking lands and islands to the South.

Throughout her life, McManus was also a prolific author, commentating in newspaper editorials and publishing several books about her life and political ideology. She wrote for the Philadelphia Public Ledger, New York Tribune and New York Morning Star, of which she was part owner. Her books include Texas and Her Presidents (1845), The Queen of Islands (1850), Eagle Pass, or Life on the Border (1852), Life in Santo Domingo (1873) and Our Winter Eden: Pen Pictures of the Tropics (1878).

In 1878 she set out for Santo Domingo on a rattletrap steamer, the Emily B. Souder, which was caught in what proved to be the largest storm recorded in the western Atlantic up to that time.

On December 12, 1878 Jane McManus died at sea at the age of 71, still doing the work she loved.

The McManus Legacy

Although it appeared that her schemes and speculations failed, many of the policies Jane McManus advocated eventually succeeded. She promoted the need for a steam navy and merchant marine fifty years before Alfred T. Mahan. She wrote about the problems of the working class sixty years before it became a Progressive crusade, advocated agrarian reform fifty years before Populists took up the cause, and assisted republican revolutionaries a hundred years before the United States awoke to the needs of the ordinary people in the sister republics of the Western Hemisphere.

McManus’ letters, books, journal and newspaper articles leave little more than a hint of her intelligence and conversational wit, a mere suggestion of her sexuality and explosive temper, a glimpse of her courage and spirituality, and a trace of her sense of humor reflected in the sparkle of violet eyes beneath raven hair and a dark complexion that was her distinguishing trait.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Jane Cazneau

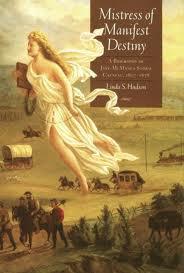

Mistress of Manifest Destiny

History Today: Storm Over Mexico

Jane Maria Eliza McManus Cazneau