Author of The Women of the American Revolution

Elizabeth Ellet was an author and historian. She was the first writer to record the lives of women who had made significant contributions during the American Revolution. Ellet not only recovered the history of women of that era; she recognized the importance of preserving these stories, which had been ignored by other American historians.

Early Years

Elizabeth Fries Lummis was born October 18, 1818 in Sodus Point, New York. Her mother was Sarah Maxwell Lummis, daughter of Revolutionary War captain John Maxwell, who was lieutenant of the first company raised in Sussex County, New Jersey. He later joined the army of General George Washington as captain of a company of 100 volunteers known as Maxwell’s Company.

Her father was William Nixon Lummis, a prominent doctor who studied medicine in Philadelphia under the famous physician Dr. Benjamin Rush. In the early 1800s, Dr. Lummis left Philadelphia and purchased the Pulteney estate in Sodus Point, New York. Elizabeth attended Aurora Female Seminary in Aurora, New York, where she studied, among other subjects, French, German and Italian.

Literary Career

In 1835 at age 16, Elizabeth published her first book, entitled Poems, Translated and Original, which included her own poems and some she had translated from French, Italian, German and Spanish. The volume also included Ellet’s Teresa Contarini, a tragedy in five acts based on the history of Venice, which was successfully performed in New York and other cities. She also contributed to several periodicals, including Knickerbocker, Lady’s Book and American Monthly.

At the age of 17, Elizabeth married William Henry Ellet, a chemist and Columbia College grad from New York City. The couple moved to Columbia, South Carolina, when Ellet was made professor of chemistry, mineralogy and geology at South Carolina College in 1836.

During this time Elizabeth Ellet published several books: The Characters of Schiller (1839); Scenes in the Life of Joanna of Sicily (1840), a history of the lifestyles of female nobility; and Rambles about the Country (1840), her observations while traveling throughout the United States.

Ellet was a prolific author in several different genres. While living in South Carolina, she wrote for regional publications such as Southern Literary Journal and Monthly Magazine and Southern Literary Messenger, while still contributing to national magazines and newspapers, including Democratic Review, New Yorker, Harper’s and Union Magazine. She also continued writing poetry and essays on European literature.

Dirty Rotten Scandals (pun intended)

In 1845, Ellet left her husband in the South and moved back to New York City where she became a member of a literary society that included Margaret Fuller, Anne Lynch Botta and Rufus Griswold. It is not clear why a woman with Ellet’s many talents and good name would involve herself – more accurately, interject herself – into not one, but two public scandals.

Poe / Osgood Scandal

Edgar Allan Poe published ‘The Raven’ in 1845, and soon became the darling of the New York City literary salons, where he attracted the interest of poet Frances Sargent Osgood. After meeting in person the love birds published several poems to each other, some under pseudonyms; but the writers’ identities were thinly veiled, and the gossip around town was that Poe and Osgood were carrying on a semi-¬public courtship.

During this time, Elizabeth Ellet sent anonymous amorous letters to Poe, and spent time with Poe discussing literary matters. Ellet began spreading rumors that Poe and Osgood were engaged in an illicit affair. Why should this be so disturbing? They were both married – Frances to artist Samuel Osgood, from whom she was estranged, and Poe to his first cousin Virginia Clemm.

While visiting Virginia Poe in January 1846, Ellet read one of Osgood’s letters to Poe which was filled with what Ellet called fearful paragraphs. Ellet took this information to Osgood, implying that they were an indiscretion. Osgood was already worried about her reputation because she had recently discovered that she was pregnant.

Osgood sent her friends Margaret Fuller and Anne Lynch Botta to retrieve her letters. Poe was angered by their interference; he surrendered the letters, but not before stating that Ellet should worry about her own compromising letters. This remark led to a threatened duel with Ellet’s brother, and greatly affected Virginia Clemm Poe, who was housebound with tuberculosis.

Osgood’s husband, Samuel Osgood, threatened to sue Ellet unless she formally apologized. She retracted her statements in a letter to Osgood saying, “The letter shown me by Mrs. Poe must have been a forgery created by Poe himself.” She suggested the incident was because Poe was “intemperate and subject to acts of lunacy.” The rumor that Poe was insane was spread by Ellet and others and eventually reported in newspapers.

After Osgood reunited with her husband, the scandal died down, but Ellet had already done permanent damage to Frances Osgood’s reputation. However, within a few years three of the main participants were dead: Virginia died in 1847, Poe in 1849, and Frances Osgood in 1850. Shortly before his death, Poe bitterly remarked that literary women were “a heartless, unnatural, venomous, dishonorable set, with no guiding principle but inordinate self-esteem.”

Rufus Griswold Scandal

The second scandal involved Rufus Griswold, who was jealous, petty and lashed out at others without reason. However, he had always treated Ellet well and even helped her publish one of her books. So there was no apparent reason why Ellet would involve herself in Griswold’s love life.

In 1852, Griswold ended his second marriage with Charlotte Myers to marry Harriet McCrillis. Although both women were complete strangers to Ellet, she took it upon herself to urge Myers not to allow the divorce and begged McCrillis not to marry Griswold. Nevertheless, the divorce was made official and Griswold married McCrillis.

However, Ellet continued writing to Myers, urging her to have the divorce repealed. Myers finally relented. While the parties waited for the case to be brought before the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas, Rufus Griswold’s house caught fire, and he was badly burned – losing his eyebrows, eyelashes and several fingernails.

When the divorce case was finally held in 1856, neither Myers nor Griswold were present, but Mrs. Ellet was there to serve as a character witness against Griswold. The divorce was not repealed, but

amidst rumors of a possible bigamy, Harriet McCrillis left Griswold, and he died of tuberculosis in 1857. Shortly before his death, Griswold published a pamphlet: Statement of the Relations of Rufus W. Griswold with Charlotte Myers… [and] Elizabeth F. Ellet…

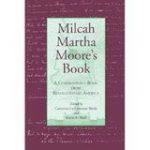

The Women of the American Revolution

Although Elizabeth Ellet was not the first woman historian in America, she was the first women’s historian. Her most significant contribution to the history of American women is her book, The Women of the American Revolution (1848-1850). These three volumes include the life stories of 160 women and document their contributions to the Revolutionary War and the formation of the new nation, the United States of America.

Her primary source materials included sifting through many unpublished letters and diaries and interviews with descendants of women of the American Revolution; she was the first historian to undertake this monumental task. Ellet noted the “abundance of materials for the [masculine] history of action” and attempted to add balance by telling the feminine side, referring to the founding mothers as giving “nurture in the domestic sanctuary of that love of civil liberty which afterwards kindled into a flame and shed light on the world.”

Ellet told the stories of women from every colony and from all social classes except African Americans, whose contribution she ignored. Some of the women she wrote about were already famous in their own right: Martha Washington, Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren and Ann Eliza Bleecker. She also profiled women who were not so well known, such as the wives of Revolutionary heroes who continued to raise their children and defend their homes without a male presence.

It is almost impossible now to appreciate the vast influence of woman’s patriotism upon the destinies of the infant republic. We have no means of showing the important part she bore in maintaining the struggle, and in laying the foundations on which so mighty and majestic a structure has risen. We can only dwell upon individual instances of magnanimity, fortitude, self-sacrifice and heroism, bearing the impress of the feeling of Revolutionary days, indicative of the spirit which animated all, and to which in its various and multiform exhibitions, we are not less indebted for national freedom, than to the swords of the patriots who poured out their blood.

In 1850, Ellet’s husband joined her in New York City, where he spent his final years as a chemical consultant for the Manhattan Gas Company.

Other Publications

Now an established and respected author, Ellet went on to write Family Pictures from the Bible (1849); Evenings at Woodlawn (1850), a collection of German legends and traditions; and Domestic History of the American Revolution (1850), which was told from the perspective of both men and women; Watching Spirits (1851); Pioneer Women of the West (1852); Novelettes of the Musicians (1852) and Summer Rambles in the West (1853), which was inspired by a boating trip on the Minnesota River.

In 1857 Ellet published The Practical Housekeeper: A Cyclopedia of Domestic Economy, a 600-page encyclopedia of home economics. She wrote in the preface, “No complete system of Domestic Economy, within the limits of a convenient manual, has been published in this country.” It includes thousands of recipes and advice with references to philosophers, scientists and ancient civilizations.

Late Years

Ellet’s later works include Women Artists in All Ages and Countries (1859), the first history of women artists; The Queens of American Society (1867); and Court Circles of the Republic: Or, The Beauties and Celebrities of the Nation; Illustrating Life and Society Under Eighteen Presidents; Describing the Social Features of the Successive Administrations… (1869), a look at the social life of eighteen presidents from George Washington to Ulysses S. Grant. In 1857 Ellet replaced Ann Stephens as literary editor of the New York Evening Express.

Ellet’s husband died in 1859. Although they had no children, she promoted charities for impoverished women and children by speaking in public to raise funds.

Elizabeth Ellet died June 3, 1877 of Bright’s Disease at age 58, and was buried beside her husband at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Complacent political and military historians, following the traditions of their craft, had left women out of their chronicles of the American Revolution; Mrs. Ellet in a domestic history of that cataclysm partly restored the balance of justice.”

~Historian Mary Beard

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Elizabeth F. Ellet

The Scandalous Elizabeth F. Ellet

NYmag: Quoth Raven, “More! More!”

Portraits of American Women Writers: Elizabeth F. Ellet