Slave in New Amsterdam

Dorothy Creole was one of the first black women in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam on the island of Manhattan. She was African, but she came from a world where West Africans and Europeans had been trading for two centuries and their cultures had mixed. She may have spoken Spanish or Portuguese, in addition to her African language. The name Creole may have begun as a descriptive term used by Europeans, and later developed into a surname.

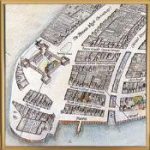

Dorothy might have arrived in 1627, when records indicate that three enslaved women were brought into New Amsterdam, which was little more than a muddy village with thirty wooden houses and a population of less than two hundred people. All slaves brought into the colony during its early years were the property of the Dutch West India Company, the founder and owner of the Colony.

Dorothy and other African women were brought to the colony because the male slaves needed wives, and Dutch women needed help keeping house. Family survival depended on the work of women: cooking, growing a garden, preserving food, raising children, making clothing, keeping the house and laundry clean, and taking care of people who were injured or sick. White women and black women may all have worked at these tasks, but female slaves probably did the hardest, riskiest, and dirtiest jobs.

Dorothy married Paulo d’Angola, who was one of the first group of slaves brought to New Amsterdam 1625. Paulo’s last name was the most common surname among the slaves, and it meant that he came from Angola, on the southwestern coast of Africa.

One day in 1643, Dorothy went to the Dutch Reformed Church to serve as godmother for a black baby named Antonio. When the boy’s parents died a short time later, Dorothy and Paulo adopted him.

When Antonio was still a baby, a Dutch sea captain named Jan de Fries came to New Amsterdam to help fight the Indians. Traveling sea captains were often given special treatment, and this may be why Dorothy and Paulo became the Captain’s slaves for a time.

In 1644, Paulo and a group of other slaves petitioned the Company for their freedom, and won. The Company’s director, Willem Kieft, freed the men and their wives, but they weren’t completely free. Former slaves were required to pay a yearly tax, to work for the colony when needed, and their children would always be slaves. This was called half-freedom.

These men and their wives received the title to land in an area north of the town, where they would act as a buffer against attack from Native Americans. Black farmers soon owned a two-mile long strip of land from what is now Canal Street to 34th Street in Manhattan, which became known as the Land of the Blacks.

The leadership of the Dutch colony clearly recognized the value of the African population. They still had to pay the tax, and could be called to work for the Dutch West India Company at any time. But they had homes of their own, and the chance to establish one of the first free black communities in North America.

The freed slaves were not treated as if they were white, but they were land owners living in a community of their peers. Blacks who were still slaves could look at Dorothy and Paulo and take hope. There was a way out of slavery.

From New Amsterdam’s earliest years, enslaved people were black and free people were white, but the lines between the two were not as sharply drawn as they became later. There were cases of Dutch and African people marrying in the Dutch Reformed Church. Captain de Fries had a son, named John, with a mixed-race woman.

After the captain died, Dorothy and Paulo were put in charge of young John’s money and property. Dorothy may have helped to raise him as well, as she raised Antonio.

Dorothy’s story illustrates how the lives of blacks and whites intersected during the Dutch colonial period in New Amsterdam.

SOURCE

Slavery in New York