Wife of Founding Father Peyton Randolph

Peyton Randolph and Elizabeth Harrison were married on March 8, 1746; they were among Williamsburg, Virginia’s leading citizens in the quarter century before the American Revolution. A second-generation Virginian, Peyton Randolph studied law in London and became Attorney General of Virginia in 1744. Though they had no children of their own, the Randolphs undoubtedly raised several of Elizabeth’s younger siblings after her parents’ early deaths.

The date of Elizabeth Harrison’s birth is unknown. Her parents – Benjamin and Anne Carter Harrison – were both deceased by 1745, leaving nine children, the youngest only three years old. When Elizabeth married Peyton Randolph in 1746, some of the children went to live with their only other married sister, while the rest almost certainly moved to Williamsburg to live with Elizabeth and her new husband. There, all the boys eventually attended the College of William and Mary just down the street from the Randolphs house. Peyton and Elizabeth had no children of their own.

Born the second son of Sir John and Lady Susannah Randolph, Peyton Randolph’s first name was the maiden name of his maternal grandmother. When he was three or four years old, the family moved into the imposing wooden structure on Market Square now known as the Peyton Randolph House. His father, among Virginia’s most distinguished attorney’s, died when Peyton was 16, leaving the house and other property for him in trust with his mother. His father’s will also gave Peyton his father’s extensive library in the hope he would “betake himself to the study of law.”

Attentive to his father’s wishes, Peyton Randolph attended the College of William & Mary, then learned the law in London’s Inns of Court. He entered the Middle Temple on October 13, 1739, and took a place at the bar February 10, 1743. Returning to Williamsburg, he was appointed the colony’s attorney general by Governor William Gooch on May 7, 1744. At the age of 24, Randolph was eligible for his inheritance. On March 8, 1746, he married Elizabeth Harrison, and on July 21 (more than two years after his return from London), he qualified himself for the private practice of law in York County.

Peyton Randolph was named Speaker of Virginia’s House of Burgesses, and on the eve of the Revolution he was unanimously elected president of the First Continental Congress at Philadelphia in 1774. He was voted president of the Second Continental Congress as well, but relinquished the post to John Hancock in order to oversee the revolutionary activities of Virginia’s new General Assembly.

Elizabeth Randolph, like most women of the landed gentry in the colonial South, spent much of her time managing household affairs and directing the slaves who maintained the property she shared with her husband. Yet she wasn’t averse to physical labor. When supplies ran short during the American Revolution, she organized the effort to render desperately needed salt from the saline river water. And while most residents fled Williamsburg when the occupying British army brought smallpox, Elizabeth Randolph stayed behind to care for the infected child of an absent family.

Peyton Randolph was on the black list of patriots the British proposed to arrest and hang after he presided over the Continental Congress in 1775. Upon his return to Williamsburg, the volunteer company of militia of the city offered him its protection.

Randolph returned to Philadelphia to rejoin the Congress in the fall of 1775. About 8 p.m. on Sunday, October 23, Peyton Randolph began to choke, a side of his face contorted, and he died of a stroke. He was fifty-three years old. He was buried that Tuesday at Christ’s Church in Philadelphia. His nephew, Edmund Randolph, brought his remains to Williamsburg in 1776, and he was interred in the family crypt in the Chapel at the College of William and Mary.

Widow Elizabeth Randolph opened her home to French general Jean-Baptiste-Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, when he arrived in Williamsburg with General George Washington to prepare for the siege of Yorktown in 1781. The house served as the French headquarters until they moved to the field.

Elizabeth Randolph remained in the Williamsburg house until her demise in 1783. Peyton Randolph’s estate was auctioned on February 19, 1783. Thomas Jefferson bought his books. Among them were bound records dating to Virginia’s earliest days that still are consulted by historians. Added to the collection at Monticello that Jefferson sold to the federal government years later, they became part of the core of the Library of Congress.

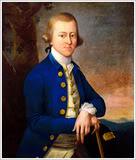

Image: Peyton Randolph House

This deep red two story Colonial house is one of the oldest, most historic, and without doubt most beautiful of Colonial Williamsburg’s original 18th-century homes.

The Peyton Randolph House was one of the most richly furnished in pre-Revolutionary Williamsburg. Acquired by Colonial Williamsburg in 1938, it was partially restored and opened to the public in 1968. The house soon became one of the foundation’s most visited sites, but questions about its original appearance arose almost immediately. Colonial Williamsburg’s archaeologists uncovered the massive foundations of a combination kitchen, laundry, and slave quarter, complete with its original vaulted brick cellar. Other foundations showed that the kitchen was attached to the house by a covered way.

A host of additional outbuildings were discovered as well, including two dairies, a smokehouse, a granary, and two storehouses, all adjacent to the house. A huge stable and coach house stood at the opposite end of the lot, together with eight acres of pasture and perhaps a garden. These structures not only restore the historic landscape but also provide the opportunity to interpret the lives of the twenty-seven slaves who lived and worked there.

No family in Colonial Virginia was more prominent or more powerful than the Randolphs. “You must be prepared to hear the name Randolph frequently,” wrote a French traveler to Virginia in the 1780s, who recognized the Randolphs as one of the most numerous and wealthiest of the first families of the colony. When writing Moby Dick in 1851, Herman Melville cited the Randolphs as the quintessential “old established family in the land,” the ultimate contrast to those families whose sons were forced into the perilous profession of whaling.

SOURCES

Peyton Randolph

Peyton Randolph House Williamsburg VA