Educator and Author of Science Textbooks

Almira Phelps was a 19th century educator and author who published several popular science textbooks, the most famous of which was Familiar Lectures on Botany (1829). Although it was received with condescension by male scientists, this book introduced a new style of science book for young students and influenced women to study the natural sciences. She wrote textbooks in all major fields of science except astronomy.

Almira Hart was born on July 15, 1793, in Berlin, Connecticut, the youngest of seventeen children. She grew up in a family of intellectuals who prized independent thinking, and received much of her education at home, where her siblings debated literature and politics. She was also an avid reader and spent some time studying in local district schools.

Career in Education

At the age of sixteen, Almira became a teacher at the Berlin Academy. In 1810 she moved to Middlebury, Vermont, to live and study with her sister Emma Willard, who had recently married the town physician. Emma’s nephew John Willard, a student at Middlebury College who boarded at her home, tutored Almira in the courses he was studying at his all male college, such as mathematics and philosophy.

This experience illustrated the disparity between the education available for men and for women, and Almira spent the rest of her life fighting for more educational opportunities for females. By 1813 she had returned to teaching in Berlin and in New Britain, and then briefly ran a boarding school for young women at the Hart family home. In 1816 became principal of a female academy in Sandy Hill, New York.

Almira’s career was put on hold in 1817 after she married Simeon Lincoln, editor of the Connecticut Mirror and moved to Hartford. She gave birth to three children, two of whom survived infancy. After her husband died of yellow fever in 1823, Almira accepted Emma Willard’s invitation to teach at her new Troy Female Seminary in New York, where she remained for eight years.

Writing Career

While she used both writing and speaking to reach a wider audience, Almira Phelps is most widely known as a writer of science textbooks. While at the Seminary in Troy she developed an interest in botany, attending lectures given at the Troy Lyceum by Amos Eaton of the Rensselaer School, who later tutored Almira in the sciences.

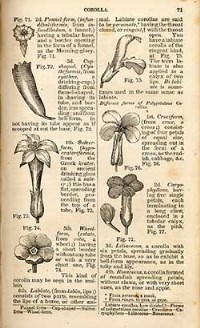

Since there were no introductory textbooks for secondary and college students, in 1829 Almira wrote her first and most successful textbook, Familiar Lectures on Botany, which was inspired by Eaton’s Manual of Botany. Over a period of forty-three years, Familiar Lectures went through twenty-eight different printings. It was illustrated with numerous woodcuts and elegant engravings copied from Mirbel’s Elements de Botanique and filled with stories and poetry.

Image: Illustration from Phelps’ Familiar Lectures on Botany

Between 1829 and 1837, Almira Phelps established herself as a reputable writer by publishing ten books, most focusing on botany and the education of young women: Lectures to Young Ladies (1833), Botany for Beginners (1833), Geology for Beginners (1834), Chemistry for Beginners (1834), Natural Philosophy for Beginners (1836), Lectures on Natural Philosophy (1836) and Lectures on Chemistry (1837).

Her Lectures to Young Ladies were speeches that were first delivered to the pupils of Troy Female Seminary when she was acting principal in 1830-1831 while Emma Willard was traveling in Europe. In these lectures Phelps offered her views on all topics pertaining to the education of women – from physical education to history to music.

Phelps became a household name through her writings and lectures. Her textbooks became the standard across the United States and Canada, and received praise as excellent educational tools for women. Unlike some of her contemporaries, her did not justify the study of science at women’s academies for the sole purpose of improving women’s domestic duties in cooking and nutrition.

While Phelps believed that the sphere of woman’s duty was in private and domestic life, she also added:

If genius, circumstance of fortune, or I might better say, the providence of God, assigns to her a more public and conspicuous station, she ought cheerfully to do all that her own powers, aided by the blessing of God, can achieve.

Her fictional writing further underscores her support of equal education for women. In Ida Norman (1848) and The Blue Ribbon Society (1872) Phelps portrayed self-indulgent young ladies whose lives were transformed for the better by the trials of life and who did not always choose to marry.

Second Marriage

Almira took a break from her work in 1831 when she married Judge John Phelps of Guilford, Vermont, a widower with six children. They had two more children together. During the next seven years Almira Phelps continued to write and edit her Troy lectures and textbooks, while raising her children and stepchildren in Guilford and Brattleboro, Vermont.

Phelps also wrote new textbooks on chemistry, natural philosophy and education. With these new books and her lectures, Phelps’ became more famous. She was asked to head many female seminaries but always declined until 1838, when she accepted a position as principal of the Young Ladies’ Seminary at West Chester, Pennsylvania. She stayed there for one year, and then became head of the Female Institute of Rahway, New Jersey for two years.

Invited by the Episcopal Bishop of Maryland, Phelps became the principal and her husband the business manager of the Patapsco Female Institute at Ellicott’s Mills, Maryland in 1841. At the time of her arrival, the school was in shambles. Phelps and her husband used their own funds to renovate the building.

Through her work, Phelps transformed the Institute into a place of high academic standards. Determined to deter her students from the era’s idealization of frail, helpless women, Phelps taught the young women not only the traditional feminine courses of music and art, but also history, mathematics and natural science – subjects usually reserved for young men.

During her fifteen years at Patapsco, she diligently applied the Troy principles of women’s education and attracted young daughters to an academy that was distinctively both female and

southern. Many of the school’s graduates went on to become highly qualified teachers.

Widowed again in 1849, Phelps pursued her work at Patapsco until the death of her eldest daughter, Jane Lincoln, in a train accident. In 1856 Phelps retired from the Patapsco Female Institute at the age of 62 and settled in Baltimore. In her remaining years she frequently wrote essays and reviews for literary magazines. Her other books include Christian Households (1858) and Hours with My Pupils (1859).

In 1859, at age 66, she became the second woman to be elected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science, following Maria Mitchell.

Late Years

During the Civil War Almira Phelps edited a ‘national book,’ Our Country in Its Relation to the Past, Present and Future (1864), dedicated by the women of Maryland as a fundraiser for the U.S. Christian and Sanitary Commissions. Our Country featured articles in prose and verse by mostly Northern authors, including Sarah Josepha Hale and Lydia Sigourney.

It was presented in the tradition of antebellum gift books, and featured essays by nonpoliticians in an attempt to regain the support of “our erring brethren of the South.” In her “Historical Sketch” included in the volume, Phelps described a country that has been tainted by the “fatal curse” of slavery, whose glorious past has been “dimmed with the tears which fall from mourners’ eyes throughout the land.”

After the Civil War Phelps supported educational equality for women, a radical idea at the time. She created the Society for the Liberal Education of Southern Girls to help young women finish their education and serve as teachers in the New South.

However, she was a staunch opponent of women’s suffrage, writing numerous articles against women being allowed to vote and joining the Women’s Anti-Suffrage Association. In the end, she advanced not only equity in education, but the cause of suffrage that she so vehemently opposed.

Almira Phelps died in Baltimore on her ninety-first birthday, July 15, 1884, leaving a legacy of science textbooks and a model for the education of young women.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Almira Hart Lincoln Phelps

Britannica: Almira Hart Lincoln Phelps

American National Biography Online: Almira Phelps

Portraits of American Women Writers: Almira H. L. Phelps

It would be very helpful if you cited the specific source for the portrait!