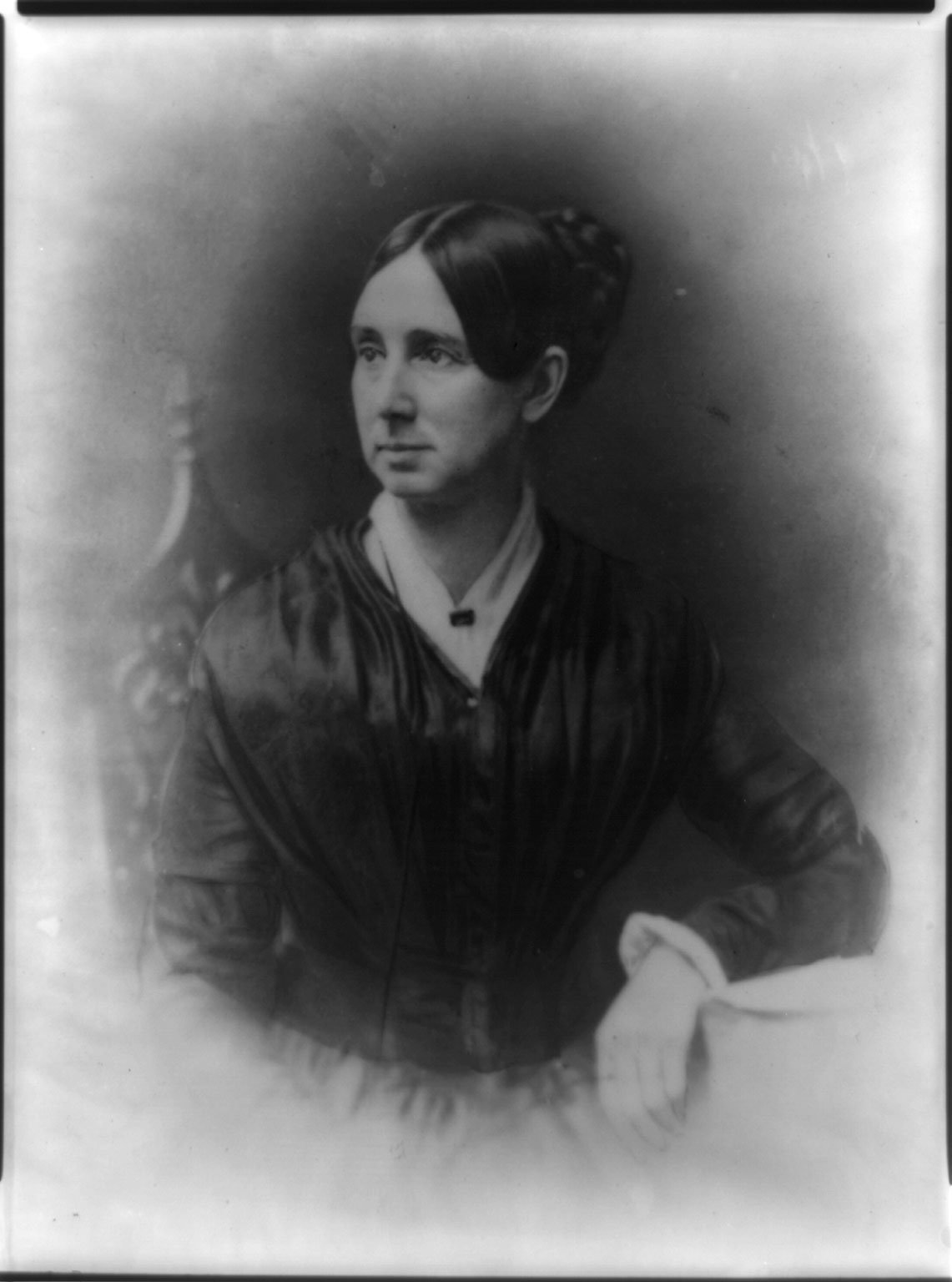

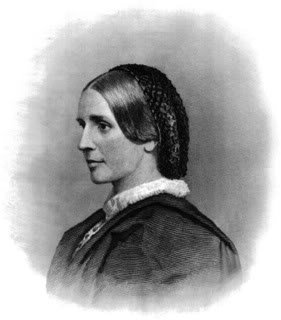

Educator, Social Reformer and Humanitarian

Dorothea Dix (1802–1887) was a social reformer, primarily for the treatment of the mentally ill, and the most visible humanitarian of the 19th century. Through a long and vigorous program of lobbying state legislatures and the U.S. Congress, Dix created the first generation of American mental hospitals. During the Civil War, she served as Superintendent of Army Nurses for the Union Army.

Dorothea Lynde Dix was born on April 4, 1802 in Hampden, Maine. She was the first child of three born to Mary Bigelow Dix and Joseph Dix, an itinerant Methodist preacher. Her mother suffered from depression and was bedridden during most of Dorothea’s childhood. Her father was an abusive alcoholic. After her mother gave birth to two more children, Joseph and Charles, Dorothea assumed responsibility for their care.

In 1814 Madame Dix, Dorothea’s seventy-year-old paternal grandmother, decided that her son and his wife were no longer capable of caring for their children. Madame Dix took the three children to live at the Dix Mansion in Boston, and sent their parents off to live with relatives.

Madame Dix was wealthy and demanded that Dorothea behave like a wealthy girl. She hired a dance instructor and a seamstress to cater to Dorothea’s personal needs. However, she was not interested in these things. Her grandmother punished Dorothea severely when she tried to give her new clothes to beggar children who were standing at their front gate.

Madame Dix then sent Dorothea to live with her sister, Mrs. Duncan, in Worcester, Massachusetts to be turned into a lady. At her great aunt’s house Dorothea immediately tried to take on the role of young lady so she could return to her brothers. However, she remained with her aunt for nearly four years.

Though Dorothea received little formal education, her appetite for knowledge was insatiable. She attended public lectures, read widely, and made a point of keeping company with knowledgeable people. She studied literature, history and the natural sciences with a special emphasis on botany and astronomy.

Career in Education

At a party for her rich relatives Dorothea Dix met her second cousin, Edward Bangs, a well-known attorney who was fourteen years her senior. Edward took an immediate interest in Dorothea. When she expressed an interest in being a schoolteacher, Edward volunteered to help by finding her students and a place in which to conduct a school.

Unusually mature and intellectually gifted at age 14, Dix opened a private school in a store Edward had found on Main Street in Worcester. She faced her first twenty pupils between the ages of six and eight in the fall of 1816. She ran this school of sorts for three years. All this time Edward continually visited her, and she was grateful to him for making her dream of being a teacher come true.

When Dorothea was 18, Edward Bangs, then 31, told her that he had fallen in love with her. Frightened and apprehensive she immediately closed her school and returned to the Dix Mansion in Boston. Edward followed her there and proposed marriage. Dorothea accepted his proposal but would not agree to a definite date for the wedding, possibly because she feared that her marriage would become like that of her parents.

By 1821, she was again residing with her grandmother in Boston. Dorothea’s father died in New Hampshire that spring. About that same time she decided not to marry Edward Bangs and returned his engagement ring. She became a devout Unitarian and embraced their religious commitment to work for the good of society.

In 1822 Dorothea opened a private school for wealthy young girls in Boston (1822-1836), but she ran a free evening school for poor and neglected children as well, one of the first in the nation. She also wrote a number of books for children and parents: Conversations on Common Things (1824), Meditations for Private Hours (1828), The Garland of Flora (1829) and American Moral Tales for Young Persons (1832).

During this time, Dorothea was often bothered by periods of poor health. In 1830 she was asked by her good friend Unitarian preacher Dr. William Ellery Channing if she would accompany his family to St. Croix in the Virgin Islands and be a tutor and governess for his daughters there. During her time on the island she was able to fully recover her health.

In 1831, Dorothea Dix returned to Boston and opened another school on the grounds of her grandmother’s estate. She soon received news that her good friend General Levi Lincoln had been elected Governor of Massachusetts and his Secretary of State was her former fiance Edward Bangs. These two individuals would later become influential in helping Dorothea in her work for the mentally ill.

In 1836 Dix began taking care of her sick grandmother and continued teaching at her school. However, her work was often interrupted by a recurring and severe upper respiratory ailment, probably tuberculosis, aggravated by a work schedule that afforded too little time for sleep. Upon her doctor’s urging she gave up her school and took an extended rest.

With a letter of introduction from Dr. Channing, Dix moved to Liverpool, England where she stayed in the home of Unitarian philanthropists, William and Elizabeth Rathbone. The Rathbones took a great liking to Dix and treated her with more affection than she had ever known in her own family. While she was there her mother and grandmother died withing two days of each other.

The Rathbones invited Dix to spend a year as their guest at Greenbank, their ancestral mansion. There she met men and women who believed that the government should play an active role in social welfare. Dix was also exposed to the British lunacy reform movement, whose methods involved detailed investigations of madhouses and asylums. She also witnessed the insane being cared for with dignity and respect.

In 1837, Dix returned to the United States and discovered that her grandmother had left her an inheritance. She also traveled and executed the terms of Madame Dix’s will, visiting distant relatives and dispersed the remainder of the money under the terms of the will. Dorothea’s own inheritance, along with the royalties from her books, supported her for the rest of her life.

Career in Social Reform

Returning from England January 1841, Dorothea Dix began her second career at age 39. A friend asked if she would take over his Sunday School class for women at the jail in East Cambridge, Massacusetts. On March 28, 1841 she entered the jail and witnessed such horrible images that her life was changed forever.

Within the confines of this jail she observed prostitutes, drunks, criminals, retarded individuals and the mentally ill – lunatics they were called at the time – all housed together with no heat, no light, little or no clothing, no furniture, and without sanitary facilities. When asked why the jail was in this condition her answer was, “the insane do not feel heat or cold.” Dix secured a court order to provide heat and to make other improvements.

She read all of the available literature on mental illness and treatment facilities. She interviewed physicians about the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness. She acquainted herself with the work of reformers Philipe Pinel, Dr. Benjamin Rush and William Tuke. Her knowledge of mental disorders soon compared favorably with that of leading hospital superintendents of her day.

For the next forty years, this work was Dorothea Dix’s life. She began by visiting jails and almshouses all over Massachusetts, conducting one of the earliest social research projects in the United States. This was at a time when women seldom traveled alone or attempted to influence legislation, funding or the regulation of public institutions.

As she visited with jailers, caretakers and townspeople she made careful and extensive notes. She was particularly distressed to learn that it was common practice to house the mentally ill in jails with felons, regardless of their age or gender. She discovered that in most cases, towns contracted with local individuals to care for people with mental disorders. Unregulated and underfunded, this system produced widespread abuse.

After her survey was complete, Dorothea Dix published the results in a fiery memorial to be presented to the state legislature in 1843. Because women were neither seen nor heard at the State House, she enlisted her friend and fellow reformer Samuel Gridley Howe to present her findings to the legislature, part of which stated:

I come to present the strong claims of suffering humanity. I come to place before the Legislature of Massachusetts the condition of the miserable, the desolate, the outcast. …to call your attention to the present state of insane persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, closets, cellars, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience!

Because her convictions were so powerful, the presentation of her findings completely won over the legislature. After a heated debate over the topic, Dix won legislative support and funds were set aside for the expansion of Worcester State Mental Hospital.

Dix then traveled from New Hampshire to Louisiana, documenting the conditions of the poor and mentally ill, publishing memorials to state legislatures, and devoting enormous personal energy to working with committees to draft the legislation and appropriations bills needed to build asylums.

Although her health was poor, she managed to cover every state on the east side of the Mississippi River. Dix played a major role in the founding of 32 mental hospitals, 15 schools for the feeble minded, a school for the blind, and numerous training facilities for nurses. She was also instrumental in establishing libraries in prisons, mental hospitals and other institutions.

In 1846, Dix traveled to Illinois to study its treatment of the mentally ill. She became ill and spent the winter of 1846 in Springfield, Illinois recovering, but her report was ready for the January 1847 legislative session, which promptly adopted legislation establishing Illinois’ first state mental hospital.

Dix visited North Carolina in 1848 and called for reform in the care of mentally ill patients. In 1849, when the North Carolina State Medical Society was formed, the construction of an institution in the capital of Raleigh for the care of the mentally ill was authorized.

Dorothea Dix’s skill as a lobbyist made her the most politically active woman of her generation. By the late 1840s she was formulating an ambitious plan to assure proper facilities for the insane poor in the long term. The culmination of this work was the Bill for the Benefit of the Indigent Insane, legislation to set aside 12,225,000 acres of Federal land – 10,000,000 acres for the benefit of the insane and the remainder for the blind, deaf and dumb.

From 1848-54 she lobbied for her plan and secured passage from both the Senate and the House of Representatives. However, by the time the bill reached the White House in 1854, Dix’s friend Millard Fillmore (they corresponded regularly for years) was no longer president. President Franklin Pierce vetoed the Bill for the Benefit of the Indigent Insane, arguing that social welfare was the responsibility of the states.

Stung by the defeat of her bill, in 1854 Dix traveled to Europe to rest from her thirteen years of work for the mentally ill. In Great Britain she reconnected with the Rathbones, then conducted investigations of Scotland’s madhouses. She then began her process of inspecting jails and almshouses in France, Austria, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Russia, Sweden, Denmark, Holland, Belgium and Germany. Between 1854 and 1856 she made effective changes in the way Europeans dealt with the mentally ill.

Superintendent of Army Nurses

Soon after the Civil War began in 1861, 59-year-old Dorothea Dix was appointed Superintendent of Army Nurses by the Union Army, beating out Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell. Unfortunately, the qualities that made her a successful crusader – independence and single-minded zeal – did not lend themselves to managing a large organization of female nurses.

Dix set guidelines for nurse candidates. Volunteers had to be between the ages of 35 and 50 and had to be plain-looking. They also had to wear unhooped black or brown dresses and were forbidden to wear jewelry or cosmetics. Her purpose was to avoid sending vulnerable, attractive young women into the hospitals, where she feared they would be exploited by the men there (doctors as well as patients).

Dix often fired volunteer nurses she had not personally trained or hired (earning the ire of supporting groups like the United States Sanitary Commission). At odds with Army doctors, Dix feuded with them over control of medical facilities and the hiring and firing of nurses. Many doctors and surgeons did not want female nurses in their hospitals.

To solve the impasse, the War Department introduced Order No.351 in October 1863, which granted both the Surgeon General (Joseph K. Barnes) and the Superintendent of Army Nurses (Dix) the power to appoint female nurses. However, it also gave doctors the power of assigning employees and volunteers to hospitals.

This relieved Dix of any real responsibility and made her a figurehead. Meanwhile, her fame and influence were being eclipsed by other prominent women like Dr. Mary Edwards Walker and Clara Barton. Dix submitted her resignation in August 1865 and would later consider this ‘episode’ in her career a failure.

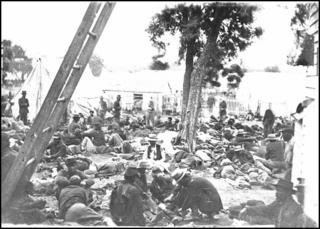

However, her even-handed care of Union and Confederate wounded alike assured her memory in the South. Her nurses often provided the only care available in the field to Confederate wounded. Georgeanna Woolsey, a Dix nurse, said, “The surgeon in charge of our camp… looked after all their wounds, which were often in a most shocking state, particularly among the rebels. Every evening and morning they were dressed.”

Another Dix nurse, Julia Susan Wheelock, said, “Many of these were Rebels. I could not pass them by neglected. Though enemies, they were nevertheless helpless, suffering human beings.” When General Robert E. Lee retreated from Gettysburg, over 5000 wounded Confederate soldiers were left behind who were then treated by Dix’s nurses, like Cornelia Hancock who wrote: “There are no words in the English language to express the suffering I witnessed today….”

Later Years

When Dix again took up work for the mentally ill, she found prospects for success now dimmed by massive immigration, a swelling population of the insane poor and much depleted state treasuries. Hospitals built earlier were now overcrowded, understaffed and in disrepair, well on the way to becoming as poor as the jails and almshouses they had replaced.

Depressed by deteriorating accommodations and programs for the insane, Dix finally retired in 1881 at age 79. She refused to talk about her achievements and wanted them to “rest in silence,” nor would she cooperate with those who inquired about her life and career.

That same year, the New Jersey State Hospital at Morris Plains opened – the first hospital to be built through Dix’s efforts. There the state legislature designated a suite for her private use as long as she lived. Since her health was failing she admitted herself into this hospital. Although an invalid, she managed to correspond with people from England to Japan.

Dorothea Dix died on July 17, 1887 at age 85, and was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In her work, Dorothea Dix was inconspicuous to say the least. She did not place her name on most of her publications, and refused to have hospitals named after her. Expressions of praise and gratitude always produced embarrassment. However, the magnitude of her work is staggering. When she began her crusade in 1843 there were 13 mental hospitals in the country; by the time she retired there were 123. Dorothea Dix played a direct role in founding 32 of them and inspired the creation of many others.

Not bad for a neglected little girl from the backwoods of Maine.

SOURCES

Dorothea Dix

Wikipedia: Dorothea Dix

Dorothea Dix Begins her Crusade

Unitarian and Universalist Biography: Dorothea Dix

can i get all the info on your dorthea pic so i can citate for a project? thx