Women Find New Power and Independence

The American Civil War illustrates how gender roles can be transformed when circumstances demand that women be allowed to enter into previously male-dominated positions of power and independence. This was the first time in American history that women played a significant role in a war effort, and by the end of the war the notion of true womanhood had been redefined.

During the decades prior to the Civil War, female activists flocked to the abolitionist movement and exerted considerable pressure on the Southern slavocracy. Authors like Lydia Maria Child published pamphlets and books condemning the institution of slavery. Although many male politicians searched for a negotiated settlement, female abolitionists refused to accept any compromise on slavery. During the first two years of the war, women delivered speeches, conducted letter-writing campaigns, and pressured President Abraham Lincoln to free all slaves held in bondage in the South.

First National Women’s Political Organization

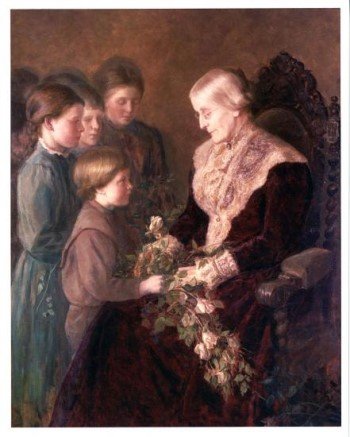

Feminists and suffragists had agreed to suspend the women’s rights conventions until after the Civil War, but many of those same women continued the fight to abolish slavery. In 1863 two leading feminist reformers, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton organized the Woman’s National Loyal League, the first national women’s political organization in the United States, to organize support for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would end slavery forever.

At the May 1863 meeting of the newly formed Woman’s National Loyal League, Lucy Stone reminded the members that while women did not yet have the vote, they had what the U.S. Constitution guarantees to all citizens, the right to petition the government. The League’s other speakers likened them all to the women of the Revolution who “were not wanting in heroism and self-sacrifice.”

Stanton and Anthony laid the groundwork for the League by publishing an “Appeal to the Women of the Republic” in the New York Tribune, an anti-slavery newspaper. They then circulated the Appeal as a tract that included the call for the convention. Anthony opened the convention and nominated Lucy Stone as president of the meeting. Other officers of the convention included such well-known figures as Martha Wright, Amy Post, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Angelina Grimke and Ernestine Rose.

Nine months later, in February 1864, the League’s first 100,000 signatures were delivered to Senator Charles Sumner in two trunks. Each contained a scroll of the amendment petitions glued end to end. He accepted the petitions with his speech The Prayer of 100,000. During the next two years, they enlisted the assistance of numerous other leading feminists. Widely praised for its work, the League ultimately collected some 400,000 signatures.

Before war’s end, their signatures, combined with other voices and pressure from Lincoln, persuaded the U.S. Senate (April 8, 1864) and the House of Representatives (January 31, 1865) to pass the proposed Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery. It was ratified by enough states to become law in December 1865.

New Frontiers for Women

When the Civil War broke out, men from all over the country enlisted in the military, leaving behind jobs and duties that women quickly filled. The war gave women the opportunity to enter the public sphere, be involved in national affairs, and function with a type of independence foreign to most of them.

Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, a female soldier from the 153rd Regiment serving the New York State Volunteers, was one of the few who openly wrote home about her gender and the struggles she faced in the course of the war. In one letter she wrote her family “I am as independent as a hog on ice.” She saw the war as a source of freedom from her strict home.

Women did not have to be soldiers to experience this new independence. Women on the home front ran businesses, joined national organizations and supported the cause through any means available. Many were excited to leave behind the strict restrictions society had placed on them. Like Little Women author Louisa May Alcott, who served as a nurse, there was an urge to contribute. She wrote in the beginning of her Hospital Sketches: “I want to do something.”

The Civil War also granted women greater access to newly developing industrial jobs and economic household power. With more and more men entering the conflict, women were required to oversee farm production, plantations and rural businesses. These tasks became increasingly difficult in the South following the introduction of the Union blockade. Unable to secure goods from foreign sources, Southern women assumed responsibility for sustaining the food supply for both the troops and the home front.

Other shortages forced them to produce cotton and wool clothing, construct tents, sew flags and manufacture medical bandages. Wealthy women supervised lumber mills, widows served as government clerks, and other women became schoolteachers. Although critical shortages would contribute to their ultimate defeat, Southern women performed duties well beyond their prewar domestic sphere, and their efforts enabled the Confederate Army to withstand and survive countless material hardships.

Northern Women

Wartime production created an unprecedented need for industrial goods in the North. Clothing, munitions and other manufactured goods were in high demand, and with the loss of income because their husbands and sons were fighting at the front, women flocked to the mills. These opportunities, however, did not result in increased prosperity.

Women were forced to accept substandard wages, and many barely escaped starvation. In New York City, more than twenty thousand women were employed in the clothing industry as stitchers and sewers. Working fifteen-hour days, they were forced to pay for their own thread and any damaged goods, but these women refused to accept their fate.

In 1863, they formed the Working Women’s Union, and by the end of the war, they were able to mobilize female clothing workers throughout the Northern industrial belt. These efforts eventually helped to produce greater female participation in the emerging American labor movement, which significantly contributed to the rise of modern feminism in post-Civil War America.

Despite all the adversities and difficulties women suffered on the home front, their contributions on the military front as nurses and spies provided vital support throughout the war. In mid-1861, Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to earn an medical degree, helped to organize the Women’s Central Association of Relief, which helped to inspire the creation of the United States Sanitary Commission.

The Sanitary Commission subsequently raised funds for medical supplies, recruited and trained nurses, and labored to improve sanitation in Army camps. Through the establishment of local chapters, the commission ensured that soldiers received their back pay and pensions. It provided help for disabled veterans, obtained jobs for soldiers’ wives, and by the war’s end, raised more than $50 million.

Dorothea Dix, a prison reformer and advocate for the mentally ill, also trained nurses and was eventually appointed as Superintendent of Army Nurses. Clara Barton labored in hospitals and battlefields as a one-woman aid society. She helped families locate relatives missing in action, and helped to provide a dignified grave site for more than thirteen thousand men who perished at the notorious Andersonville prison in Georgia. These accomplishments generated long-term gains for women.

Southern Women

Women in the South followed similar paths. Several middle- and upper-class women quickly erected army hospitals following the outbreak of hostilities. In Virginia, Sally Tompkins, who later received a commission as a captain in the Confederate Army, established a hospital in Richmond. Other women served in military stations at the front and helped to create fund-raising agencies similar to the United States Sanitary Commission.

Hospital work allowed women to show their patriotism, help maintain soldiers’ morale, and genuinely contributed to the Confederate war effort. At the start of the war, Juliet Hopkins sold her estates in New York, Virginia and Alabama and gave the proceeds to the Confederate government to establish hospitals for Confederate soldiers. She then went to Richmond to serve as chief matron of the hospital corps for Alabama.

Motivated by everything from patriotism to poverty to a sense of vocation, many white women found themselves working outside the home and earning money for the first time in their lives. The Southern shortage of labor was so severe that even some black women, free and enslaved, found new opportunities to work for wages. The unpaid labor of enslaved women across the Confederacy also formed a critical component in supplying the war effort.

The presence of so many women in the workplace challenged the widely accepted doctrine of separate spheres – the male domain of politics and business, and the female world of household and family. This guaranteed that the workforce would never return to its prewar status and began a redefinition of women’s place in American society.

Medical work was one of the most significant ways that Confederate women contributed to the war effort. Women rarely worked as nurses outside the home in the antebellum period, but numerous wartime factors, including the lack of available manpower and Confederate women’s close proximity to battlefields, demanded their increased participation.

Most Confederate nurses were working class and enslaved women who endured grisly and dangerous conditions. Only those with the calmest stomachs were appointed to field hospitals by surgeons familiar with their skill and conduct under pressure. Most women, however, worked or volunteered in established military hospitals at military depots and near battlefields.

In Virginia, where so much of the war was fought, there were many such opportunities for dedicated women to provide essential physical and psychological care to sick and wounded soldiers. In September 1862, the Confederate Congress passed a law granting women official positions in the army medical service, and, like their Northern counterparts, Southern nurses helped to eliminate barriers for others.

The most genteel and well-paid positions were reserved for middle- and upper-class white women. The Confederate government, particularly in Richmond, hired them to sign banknotes at the Treasury, sew uniforms for the Clothing Bureau, and sort letters at the post office. Schoolhouses and academies across the Confederacy hired them to nurture and instruct children and youths.

Working class and poor women, both black and white, often entered into occupations that their wealthier counterparts considered distasteful. Factories in larger cities – particularly Richmond, also the industrial capital of the Confederacy – employed hundreds of women, whose small hands and presumed manual dexterity were considered ideal qualifications for tasks such as making ammunition.

The majority of Southern women eventually withdrew their support from the Confederate government. Many poor, working class, and even some upper-class white women came to believe that the Confederate government did not protect them or represent their interests, or simply that the cost of continuing the war was too great. This erosion of Southern women’s support for their government ultimately undermined the war effort and contributed to the fall of the Confederacy.

Some Southern women remained loyal to the United States throughout the war, and many expressed their Northern sympathies by feeding and quartering Union soldiers, hiding escaped Union prisoners, or like Elizabeth Van Lew of Richmond, serving as spies. As women suffered increasing privations on the home front, many previously loyal Confederates began voicing their discontent in diaries, newspapers and letters to the Confederate government and loved ones on the battlefront.

The war forced women into public life in ways they could scarcely have imagined a generation before. The experiences of women in the North and the South shattered the myth that women could not endure the rigors of economics, politics and hard physical labor. No longer content to sit at home and leave the decision making to men, women gained self-confidence from their ordeals, which fortified the growing feminist movement and eventually helped countless women achieve unprecedented personal success in post-Civil War America.

In the immortal words of diarist Lucy Buck of Front Royal, Virginia:

We shall never any of us be the same as we have been.

SOURCES

Historynet: Women in the Civil War

Salem Press: Women in the Civil War

Wikipedia: Woman’s National Loyal League

Encyclopedia Virginia: Women During the Civil War