First Woman Doctor in the United States

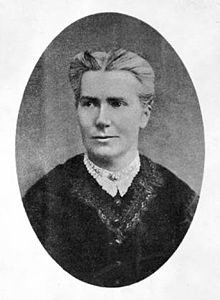

Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910) was the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States, and a social reformer in both the US and in England. By the time of Blackwell’s death in 1910, the number of female doctors in the United States had risen to over 7,000.

Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910) was the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States, and a social reformer in both the US and in England. By the time of Blackwell’s death in 1910, the number of female doctors in the United States had risen to over 7,000.

Childhood and Early Years

Elizabeth Blackwell was born near Bristol, England February 3, 1821, the third daughter among nine children of sugar refiner Samuel Blackwell and Hannah (Lane) Blackwell. Every member of the Blackwell family was involved in social reform movements. They believed in free and equal education for both sexes, which was radical thinking for that time period. Four maiden aunts also lived with the family during Elizabeth’s childhood.

Samuel Blackwell exerted a strong influence over the religious and practical education of his children. He believed that each child should be given the opportunity for unlimited development of his or her talents and abilities. Elizabeth had not only a governess, but also private tutors to supplement her intellectual development.

In the 1830s, riots broke out in Bristol, and Mr. Blackwell suffered a series of business losses. In August 1832 he decided to try his luck in the United States. The family settled in New York City, where Blackwell established the Congress Sugar Refinery. The family became deeply involved in the abolitionist movement, attending meetings and hiding an escaped slave in their home.

Elizabeth adopted her father’s liberal views, attending antislavery fairs and abolitionist meetings throughout the mid to late 1830s. These activities made her yearn for more economic and intellectual independence. In 1836, the refinery burned to the ground and was rebuilt, but Samuel Blackwell encountered business problems the following year.

In 1838 Mr. Blackwell became interested in making sugar from sugar beets instead of sugar cane, which required massive amounts of slave labor. However Samuel died unexpectedly in August 1838, leaving his family with no income. To support the family, Elizabeth and two of her sisters opened the Cincinnati English and French Academy for Young Ladies, a private boarding school.

Elizabeth became an active member of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. However, after William Henry Channing, a charismatic Unitarian minister, arrived in Cincinnati in 1839 she began attending the Unitarian Church. The conservative Cincinnati community disapproved, and the Academy lost many students and was forced to close in 1842. Elizabeth began teaching privately.

Channing renewed Elizabeth Blackwell’s interests in education and reform. She worked at self-improvement by studying art, attending lectures, writing short stories, and attending religious services of all denominations. In the early 1840s, she began to express her thoughts about women’s rights in her diaries and letters.

In 1844 Blackwell accepted a job as a schoolteacher in Henderson, Kentucky with an annual salary of $400 per year. While living there she experienced the realities of slavery first hand. Six months later she returned to Cincinnati, determined to find a better way to make a living.

An Independent Life

In 1845, at age 24, Blackwell visited a friend who was suffering from terminal cancer of the uterus. The friend said that she would have been much more comfortable being treated by a female doctor. This meeting probably gave Blackwell the idea of pursuing a career in medicine, but she also hoped that it would allow her to be financially independent.

Discreet inquiries to doctor friends concerning the possibility of acquiring a medical degree were met with incredulity or disgust, but she was not deterred. The following year, Blackwell was able to secure a post teaching in Asheville, North Carolina, where she studied medicine privately with Dr. John Dickson; the year after, she taught music in Charleston, South Carolina, while continuing her studies with Dickson’s brother, Dr. Samuel Dickson.

By 1847, Blackwell was ready to begin applying to medical schools, knowing that no woman had ever been permitted to study medicine. She then returned to Philadelphia, where her friends were mostly Quaker liberals, abolitionists and other social reformers. She had some affairs with men, and feared that her romantic tendencies would lead her to marriage, but her determination to become a doctor soon became an obsession.

However, she encountered nothing but resistance. She consulted male physicians, who advised her to study in Paris or to attend an American medical college disguised as a man. She was also told that women were intellectually inferior to men and incapable of mastering the study of medicine, and on the off chance that she might succeed she could not expect them to “furnish [her] with a stick to break our heads with.”

Medical Education

In 1847, she began applying to any and all medical schools. Her application was rejected by nineteen schools. Finally, at tiny Geneva Medical College in upstate New York, the faculty left it up to the 150 male students to accept or reject Blackwell’s application. The students thought it was a practical joke and voted to admit her.

Blackwell’s presence in the classroom greatly impacted the behavior of the male students. The boisterous young men soon became well-behaved gentlemen. However, she lived a solitary existence while at Geneva. Everyone considered her a oddity. They could not understand why she would want a medical career, when marriage and motherhood were much better goals for a woman.

In her autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women (1895), Dr. Blackwell wrote:

I had not the slightest idea of the commotion created by my appearance as a medical student in the little town. Very slowly I perceived that a doctor’s wife at the table avoided any communication with me, and that as I walked backwards and forwards to college the ladies stopped to stare at me, as at a curious anima. I afterwards found that I had so schocked Geneva propriety that the theory was fully established either that I was a bad woman, whose designs would gradually become evident, or that, being insane, an outbreak of insanity would soon be apparent. Feeling the unfriendliness of the people, though quite unaware of all this gossip, I never walked abroad, but hastening daily to my college as to a sure refuge, I knew when I shut the great doors behind me that I shut out all unkindly criticism, and I soon felt perfectly at home amongst my fellow students…

The summer after her first year at Geneva, Blackwell returned to Philadelphia and tried to find a job where she could gain clinical experience. She finally received permission to work for Guardians of the Poor, the city commission that ran Blockley Almshouse, but some young physicians there refused to work with her.

Elizabeth Blackwell graduated first in her class on on January 23, 1849, becoming the first American woman to receive a medical degree. However, the medical community was outraged, and Geneva Medical College again closed its doors to women.

Blackwell traveled to Europe for additional training. Denied access to Parisian hospitals because of her gender, she enrolled instead at La Maternite, a highly regarded midwifery school. In the summer of 1849 she began her residency in midwifery and obstetrics – under the condition that she would be treated as a student midwife, not a physician.

On November 4, 1849, while treating an infant with an eye infection, she spurted some contaminated solution into her own eye by accident. She lost sight in her left eye and thus lost all hope of becoming a surgeon. After recovery, she enrolled at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London in 1850. Paul Dubois, the foremost obstetrician in his day, voiced the opinion that she would make the best obstetrician in the United States, male or female.

Medical Career

In 1851, Blackwell returned to the United States to begin her career, but no one would hire her. In 1853, she purchased a house in a seedy area on the Lower East Side of New York City, and opened a one-room clinic – the New York Dispensary for Poor Women and Children. She had very few patients, but managed to get some media support from the New York Tribune.

From these humble beginnings, Dr. Blackwell, her sister Dr. Emily Blackwell and German physician Dr. Marie Zakrzewska expanded Blackwell’s clinic into a hospital, the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children in 1857. There they cared for pediatric, obstetric and gynecological patients, and women served on the board of trustees and as attending physicians.

Poor women came from all boroughs of New York City to this first medical facility in the United States staffed by female physicians, and the patient load doubled in the second year. The institution also served as a nurse training facility. As time went on, Elizabeth Blackwell’s interest in social causes also grew, especially the educational status of women.

When the Civil War began, the Blackwell sisters organized the Women’s Central Association of Relief, and worked with Dorothea Dix to train nurses for service in the war. The sisters and Mary Livermore also played an important role in the development of the United States Sanitary Commission. Dr. Blackwell always promoted the importance of good hygiene.

She also published two important books on the issue of women in medicine, including Medicine as a Profession For Women in 1860 and Address on the Medical Education of Women in 1864. In 1866 the New York Infirmary treated nearly 7,000 patients. She then turned her attention to her dream of establishing a medical college for women adjacent to the hospital. The Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary was opened in 1868.

Dr. Blackwell had always planned to return to England to make her career, and in 1869 she left New York to spend the remaining 40 years of her life in Great Britain. In 1874 she established the London School of Medicine for Women with Sophia Jex-Blake, who had been a student at the New York Infirmary years earlier. As her health declined, Blackwell resigned this position in 1877, and officially retired from medicine.

Social Reform

In England Blackwell diversified her interests, and was active both in social reform and authorship. She co-founded the National Health Society in 1871. She perceived herself as a wealthy gentlewoman who had the leisure to dabble in reform and in intellectual activities – the income from her American investments supported her. She traveled across Europe many times during these years, to France, Wales, Switzerland and Italy.

Her greatest period of reform activity came after her retirement, from 1880-1895. She was highly involved in a variety social reform movements: hygiene, sanitation, preventative medicine, family planning and women’s rights. She also contributed to the establishment of two Utopian communities in the 1880s.

Geneva, New York

This bronze statue was erected on the campus of the Geneva Medical College (now the Hobart and William Smith Colleges) where Blackwell graduated in 1849, becoming the first woman doctor in the United States.

Family and Friends

Blackwell was well connected, both in the United States and in England. She became very close friends with Florence Nightingale, and remained lifelong friends with English feminist and activist Barbara Bodichon, and met Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1883. She was close with her family, and visited her brothers and sisters whenever she could during her travels.

Having decided not to marry, Dr. Blackwell adopted Kitty Barry, a seven-year-old Irish orphan in 1856. Diary entries at the time show that she adopted Barry half out of loneliness and a feeling of social obligation, and half out of a need for domestic help. Barry gradually became one of the family and lived with Blackwell until her death.

Blackwell continued to be active in her retirement. In 1895, she published her autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women. She slowly disengaged from her reform work spent more time traveling. In 1907, she fell down a flight of stairs, and was left almost completely mentally and physically disabled.

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell died May 31, 1910 after suffering a stroke at her home, Rock House, in Hastings, England at age 89.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Elizabeth Blackwell

About.com: Elizabeth Blackwell

Women’s History: Elizabeth Blackwell