Abolitionist, Botanist, Genealogist, and Suffragist

Eliza Starbuck Barney was an ardent Quaker who championed abolition, temperance, and women’s rights. Her massive genealogical work contains vital information about more than 40,000 Nantucketers; it is the most reliable genealogy for Nantucket’s families for the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. The Barney Record is now the foundation of the genealogical collection and database at the Nantucket Historical Association’s Research Library.

Early Years

Eliza was born April 9, 1802 to Quakers Joseph and Sally Gardner Starbuck on the island of Nantucket, Massachusetts. Joseph Starbuck, the island’s most successful businessman, made a fortune in whale oil. Local schools offered girls equal opportunities for education with those of their brothers. During her studies, Eliza developed an enduring interest in the natural sciences, agriculture, and history.

Joseph Starbuck built three brick mansions on Main Street for his three sons during the most prosperous period of whaling. His daughters would have to depend on their husbands if they were to have such fine homes.

Marriage and Family

Eliza met Nathaniel Barney, ten years her senior, and they married in May 1820. At Eliza’s wedding, her sister Eunice met silversmith William Hadwen, and within two years they were married as well. Eliza gave birth to three children: Joseph, Sarah, and Jethro.

Barney and Hadwen went into business together as purveyors and manufacturers of oil and candles. The business thrived, and they built two Greek Revival mansions at 100 Main Street, across the street from the three Starbuck brothers.

Anti-Slavery Work

Nantucket abolished slavery in 1773, and thereafter African Americans worked as tradespeople, laborers, sheep and livestock raisers, and as whalers and mariners.

Eliza Starbuck Barney was a cousin and close friend of abolitionist, suffragist, and Nantucket native, Lucretia Coffin Mott. The Barneys kept up a life-long correspondence with Lucretia and her husband James, in which they often discussed the anti-slavery movement. In several letters, Nathaniel related his issues with the New Bedford Railroad in which he held stock. For several years, he protested and refused to accept his dividends because the railroad would not carry black passengers.

Frederick Douglass

In the spring of 1841 Nantucket banker William C. Coffin attended an anti-slavery meeting at New Bedford, Massachusetts. There he met a twenty-three-year-old runway slave named Frederick Douglass. Impressed by the young man, Coffin invited Douglass to attend a Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society Convention at the Nantucket Atheneum that summer; Douglass accepted.

Leading abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, founder of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society and editor of the Liberator, organized the convention. All Quakers and ardent supporters of the anti-slavery movement, the Barneys and the Hadwens welcomed Douglass and Garrison into their homes at 100 Main Street while they were on the island.

On August 11, 1841, Frederick Douglass rose nervously to address the audience at the Convention. He was clearly embarrassed and apologized for his ignorance, and then he began narrating several incidents of his life in bondage. Despite his shyness and faltering speech, this was the beginning of a new life for Douglass as a public speaker, abolitionist, and champion for black rights.

Underground Railroad on Nantucket

Because it was a secret operation, connections to the Underground Railroad on Nantucket are largely undocumented. However, historians describe the region as a likely destination for maritime escapes, especially due to the expansive abolitionist activities at nearby Boston and New Bedford.

Certain properties reveal evidence of underground activity – trap doors, tunnels, and odd cellars. Many of the homes owned by recognized abolitionists have long been linked to the Railroad. Quakers and Methodists assisted fugitive slaves. The presence of a free black population – 724 out of 7,300 in 1820 – and religious groups made Nantucket an enclave for abolitionists.

In the 1820s the African Meeting House was built and it became a school, church, and social center for the black community. Today, the Black Heritage Trail on Nantucket showcases a restored school and church, plus privately owned homes where runaway slaves were sheltered as early as the 1820s.

Love for Science and History

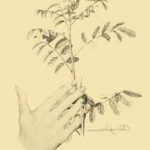

Eliza Barney’s accomplishments stretched far beyond anti-slavery work and social reform; among other interests, she taught herself botany and entomology (study of insects). This excerpt from the the Nantucket Historical Society sums up her various interests:

She was a self-taught botanist and entomologist, so respected in those fields that her obituary says she was “justly to be considered an authority for the rising generation.” And this interest would also creep into her genealogical record, as in the notation that an island man died “from a spider.” Her love of natural history, including all aspects of agriculture, was matched only by her love of history. She was, for her day, a proper “buff,” enjoying research, an inclination that made her perfectly suited to become the island’s foremost genealogist.

Eliza’s Other Social Reforms

Not only active in the anti-slavery movement, Eliza was also a supporter of the temperance movement and involved in the equal rights and women’s suffrage movements. In 1839 and 1840, Eliza served as secretary of Nantucket’s Anti-Slavery Society and in 1851, with both her daughter and husband at her side, she attended the first women’s suffrage convention held in Massachusetts.

Eliza Starbuck Barney Genealogical Record

In 1856, Eliza inherited the papers of the self-appointed Nantucket genealogist Benjamin Franklin Folger’s papers, including his genealogical work. Included were the records that would form the basis of Eliza’s life: The Eliza Starbuck Barney Genealogical Record. The Barney Record is the cornerstone of all Nantucket genealogical research.

With the help of her granddaughter, Eliza Barney Burgess, Barney recorded the island’s genealogical history starting with the first settlers in the 1600s through the early twentieth century. The result is a valuable genealogical research tool which is more accurate and informative than the Vital Records of the Town of Nantucket.

Eliza Barney filled volume after volume with a neat hand and pinpoint accuracy, documenting the family trees of Nantucketers onto 1,702 ledger pages. These pages are contained in six legal-sized, heavily bound books containing approximately 275 pages per book.

In the late 1850s, daughter Sarah moved with her husband to Poughkeepsie, New York and the Barneys followed soon after so they could be closer to their only daughter. There they also lived in the company of professors of Vassar College, including another Nantucket native, Maria Mitchell, professor of astronomy.

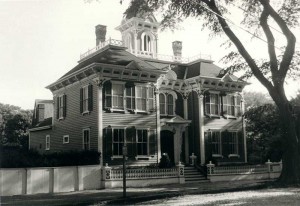

Image: Eliza Starbuck Barney House

73 Main Street, Nantucket

Nantucket Historical Association

In 1869, Nathaniel Barney died, and Eliza moved back to Nantucket, and her son Joseph built a Victorian house for his mother at 73 Main Street. She lived there until the early 1880s, when she went to live with her son Joseph at 96 Main Street, which he had inherited from William Hadwen.

Eliza enjoyed spending summers at the Hadwens’ cottage in ‘Sconset, Nantucket. A relative wrote:

One summer, Mother Barney [as she was known to her family] fell and broke her hip and spent most of the summer sitting on the porch. Everyone in the village loved her and the actors and actresses used to come over each day to entertain her.

Eliza Starbuck Barney died March 18, 1889, at the age of eighty-six, leaving a priceless genealogical legacy.

In a eulogy written not long after Eliza’s death Anna Gardner, then president of the Suffrage League of Nantucket, remembered Barney for the practical and courageous example she set:

In thinking of the loss that the Suffrage Cause has sustained in the death of Eliza Barney, my mind has gone back to the time when we were first allowed to vote for School Committee, and how some of us … dreaded to go to the polls to deposit our vote on account of the ridicule and the sarcastic remarks that we thought were sure to be expressed by some of those who felt women were out of their sphere in so doing – we had for our leaders Eliza Barney, Elizabeth G. Macy and Harriet Pierce … we took courage, and thought with these three women to lead us, we could do anything.

SOURCES

Cape Cod Times: Ties to Freedom

Nantucket Historical Association: Who Was Eliza Barney?

Frederick Douglass Heritage: Anti-Slavery Convention in Nantucket

Nantucket’s Daring Daughters: A Brief Look at Eliza Starbuck Barney