One of the First Women Scientists in the United States

Maria Mitchell (1818–1889) was an American astronomer who discovered a comet in her telescope in 1847, which became known as the Miss Mitchell’s Comet and brought her international fame. She was the first professor appointed at the new Vassar College and the first acknowledged woman astronomer in the United States.

Maria Mitchell (1818–1889) was an American astronomer who discovered a comet in her telescope in 1847, which became known as the Miss Mitchell’s Comet and brought her international fame. She was the first professor appointed at the new Vassar College and the first acknowledged woman astronomer in the United States.

Image: Maria Mitchell with her students

Early Years

Maria (pronounced ma-RY-ah) Mitchell was born August 1, 1818 on the island of Nantucket, Massachusetts, daughter of Quakers William and Lydia Coleman Mitchell. She had nine brothers and sisters. Her mother’s side of the family traced its ancestry to Benjamin Franklin.

The Quaker religion taught intellectual equality between the sexes, and the island of Nantucket was unusual for its time in regard to equality for women. Nantucket’s importance as a whaling port meant that wives of sailors lived in relative independence for months and sometimes years, managing the family’s affairs while their husbands were at sea.

Like other Quakers Maria’s parents valued education and insisted on giving their daughters the same quality of education their sons received. Not many girls born in the early 1800s were lucky enough to have a father like William Mitchell, a dedicated amateur astronomer and teacher.

Mitchell rated chronometers for use by the Nantucket whaling fleet in celestial navigation, and was delighted with the early talent his daughter demonstrated for science. Instead of considering such interests useless for a girl, he taught her mathematics and astronomy, using his own telescope at home. At age twelve, Maria helped her father calculate the exact moment of an annular eclipse.

After attending Elizabeth Gardener’s small school in early childhood, Maria attended the North Grammar school where her father William Mitchell was the first principal. Two years later, when Maria was eleven, her father built his own school. There, she was a student as well as a teaching assistant.

After William Mitchell’s school closed, Maria attended Unitarian minister Cyrus Peirce’s School for Young Ladies. Later she worked for Peirce as his teaching assistant. Maria left in 1835 at the age of 17 to open her own school to train girls in science and mathematics. She rented a room and put an advertisement in the newspaper.

Maria decided to close her school a year later in 1836 after she was offered a job as the first librarian of Nantucket’s Atheneum Library where she worked for eighteen years. This job was perfect for her – she was earning a good salary and had time to study and read many books, further developing her passion for knowledge.

While Maria spent her days at the library, she spent her nights observing the sky with her father. William Mitchell had been hired as cashier of the Pacific Bank, which came with living quarters attached to the bank. He built an observatory on the roof and installed a brand-new four-inch telescope, which he used to make star observations for the United States Coast Guard and Maria helped him with the measurements.

Career in Science and Education

On a clear night in October 1847, at the age of 29, Maria stood on that roof, focusing her telescope on a faraway star, five degrees above the North Star where there had been no star before. She had memorized the night sky and was sure of her observation. It occurred to her that this might be a comet, and recorded its coordinates. The next night the star had moved, and Maria was sure it was a comet.

Maria Mitchell became the first person to record a comet sighting in America. Not only was this a first in American science, she used a mere two-inch telescope, which illustrates her skill as an astronomer. Her father wrote to Professor William Bond at the Harvard University observatory, who submitted Maria’s name to the king of Denmark who had offered a gold medal to anyone who discovered a comet that could only be seen through a telescope.

Maria Mitchell’s quiet life on Nantucket immediately changed. The discovery of a comet was rare enough in nineteenth century America, but a woman astronomer was unheard of. She received international fame, and the gold medal from King Frederick VII of Denmark, which reads: Not in vain do we watch the setting and rising of the stars. Her discovery became known as Miss Mitchell’s Comet.

Mitchell continued working as a librarian, but she began receiving letters of congratulations from scientists, and tourists were coming to take a look at the lady astronomer. She became the first woman member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1848. Only 30 at the time, she would be the only woman thus recognized for almost a century into the future.

Maria Mitchell was the first American woman to work as a professional astronomer, and probably the first woman employed in a professional capacity by the federal government. Although women had been hired as cooks, laundresses and other domestic jobs, her 1849 employment appears to be the first case of a woman earning an annual salary for work based on knowledge of an academic field.

Mitchell worked at the U.S. Nautical Almanac Office, calculating tables of positions of the planet Venus. The U.S. Coastal Survey paid her $300 a year as a celestial observer. Much of the project’s purpose was to develop the science of weather forecasting, and it involved computing distances. She also started traveling to attend scientific meetings, and was the first woman elected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1850.

In 1856 Mitchell received an offer from a rich man named General Swift to accompany his daughter Prudence on a trip to the South and to Europe. She accepted and took her almanac work with her. They went south to New Orleans, then to London, where Mitchell visited the Greenwich Observatory. She went to France on her own, then continued on to Rome with Nathaniel Hawthorne and his family.

She met with other astronomers, including Sir John Herschel, whose aunt, German-born Caroline Herschel, who had discovered a comet in 1788, and had been a pioneering astronomer prior to her 1848 death. Mitchell also visited Scotland’s Mary Somerville, who published The Mechanisms of the Heavens in 1829 and went on to innovative work on ultraviolet rays and molecular structure.

Boston feminists were extremely proud of Mitchell’s achievements. It was botanist Elizabeth Agassiz who had persuaded her husband to nominate Mitchell for membership in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. After her return from Europe, Mitchell was presented with a new telescope bought with money collected from wealthy friends by innovative educator and publisher Elizabeth Palmer Peabody.

Before and during the Civil War, Mitchell was an outspoken opponent of slavery and stopped wearing clothes clothes made of Southern cotton. She continued her pursuit in the scientific field through the Civil War, when she also was involved in the anti-slavery movement.

The Civil War transformed the roles of American women, and many eastern states that had not provided colleges for women began to do so. One of the most prestigious was Vasser College, which was founded in Poughkeepsie, New York, by Matthew Vassar in 1865. Vassar persuaded Mitchell to join its faculty, where she was the first person (male or female) appointed to the faculty of the new school.

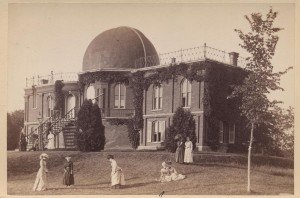

Mitchell was appointed Professor of Astronomy at Vassar College in 1865. She was also named Director of the Vassar Observatory. Mitchell and her father moved into the Vassar Observatory, the first building of the college to be completed, in the summer of 1865, and the college opened that fall.

At Vassar she had access to a twelve-inch telescope – the third largest in the United States – and continued her own study of the surface features of Jupiter and Saturn and photographing stars. She later learned that her salary was less than that of many younger male professors. She insisted on a salary increase, and was given one.

Equally important, she refused to enforce the petty rules of female behavior that were expected at that time. She often invited her students – all females – to come up to the observatory at night and watch meteor showers or other astronomical events. But the college initially insisted that her students were not allowed to go outside at night!

Mitchell edited the astronomical column at Scientific American. She made astute early observations about sunspots, the surface of Saturn and the composition of its rings, the double nebulae in the Great Bear constellation and an 1869 solar eclipse. She concluded that color variations between stars were probably caused by their varying chemical compositions.

After the war Mitchell concentrated her political actions on women’s rights, co-founding the American Association for the Advancement of Women in 1873. Mitchell had known of Nantucket-born Quaker and feminist Lucretia Mott all of her life, and she later befriended other women’s rights activists, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

In 1873 Mitchell attended the first meeting of the Women’s Congress, which was also attended by Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell and Antoinette Brown Blackwell.

Mitchell used her observatory dome at Vassar not only for the study of science, but also as a gathering place for the discussion of politics and women’s issues and her annual “dome party.” On May 10, 1875, Julia Ward Howe, (composer of the Civil War anthem “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”) lectured in the observatory on “Is Polite Society Polite?”

Mitchell used her observatory dome at Vassar not only for the study of science, but also as a gathering place for the discussion of politics and women’s issues and her annual “dome party.” On May 10, 1875, Julia Ward Howe, (composer of the Civil War anthem “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”) lectured in the observatory on “Is Polite Society Polite?”

Image: Vassar College Observatory in 1879

Late Years

When the nation celebrated its first centennial in 1876, Mitchell chaired the Women’s Congress held in Philadelphia. She was one of the first women elected to the American Philosophical Society. She was also an exceptionally good teacher, and many of her students went on to achievement in astronomy.

Mitchell never married. Throughout her career she encouraged young women to be anything they wanted to be, in the same way her father had encouraged her. Always a powerful advocate of women’s potential, she became increasingly feminist as she aged.

Mitchell retired from Vassar in 1888 because of poor health, but continued her research in Lynn, Massachusetts, where her sister lived.

Maria Mitchell died of a brain disease on June 28, 1889 in Lynn, Massachusetts, at the age of 70. She was buried in Lot 411, Prospect Hill Cemetery, Nantucket.

In 1902 friends, family members and former students founded the Maria Mitchell Association to preserve the legacy of Nantucket astronomer, librarian and educator Maria Mitchell. It operates the Maria Mitchell Observatory, a Natural History Museum, Maria Mitchell’s Home Museum, the Science Library and her home, which is open to visitors.

In 1905 Mitchell was elected to the Hall of Fame of Great Americans at New York University (now at Bronx Community College). In 1994, she was elected to the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York. She was the namesake of a World War II Liberty ship, the SS Maria Mitchell. The crater Mitchell on the Moon is named after her.

My favorite Maria Mitchell quote:

We especially need imagination in science. It is not all mathematics, nor all logic, but is somewhat beauty and poetry.

SOURCES

Maria Mitchell

Wikipedia: Maria Mitchell

Maria Mitchell, Astronomer

Distinguished Women: Maria Mitchell

National Women’s History Museum: Maria Mitchell