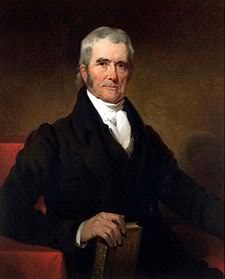

Wife of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Marshall

Image: Mary Willis Ambler Marshall

Portrait circa 1790

Mary Willis Ambler was born March 18, 1766, in Yorktown, Virginia. She was the second of five girls born to Rebecca Burwell and Jacquelin Ambler, a prominent Yorktown family, and was part of the bustling life of the port city and the nearby colonial capital of Williamsburg. Mary Marshall grew up learning many of the traditional lessons of girls at the time.

John Marshall was born on September 24, 1755, at Germantown in Fauquier County, on the Virginia frontier. He was the son of Colonel Thomas Marshall and Mary Randolph Keith Marshall, and the oldest of 15 children.

As a young boy, Marshall was influenced and encouraged by his father’s friend, George Washington. Marshall served in the Continental Army, first as a lieutenant and then as captain. Enduring the hardships of the winter at Valley Forge (1777-1778), Marshall’s admiration of Washington grew as did his resolve to help shape the new nation.

Marshall studied law with George Wythe at the College of William and Mary before being admitted to the bar in August 1780. He then established a private law practice in Fauquier County, Virginia. During this time Mary Willis Ambler and John Marshall met.

Home and Family

Family tradition holds that Marshall fell in love with Mary soon after meeting her. After spending time with her at dances, Marshall asked Mary to marry him in 1782. She was 16; he was 27. Becoming flustered, she refused. John was disappointed and quickly left her house. She soon realized her error and sent a cousin riding after Marshall to give him a lock of her hair. He returned the lock of hair, entwined with a lock of his own encased in a gold locket.

Mary married John Marshall on January 3, 1783, after a short courtship. Throughout nearly 49 years of marriage, Mary wore that locket around her neck. Marshall called Mary my dearest Polly, and shared many of his concerns about the shaping of the nation with his wife and respected her opinion on many issues. His letters to her help to build an understanding of Marshall’s character and concerns.

John and Mary had ten children, but only six survived to adulthood – five boys and one girl. The tragedies of her children’s deaths weakened Mary, whose health was never strong. She became sickly and reclusive. During the last 25 years of her life, she usually stayed at home, often in the master bedroom. Her frailty and illness, however, did not diminish the deep love she and John had for each other.

On the morning of her death, Polly tried to remove the locket from around her neck. She was so weak that John had to help her; she wanted to see him put the keepsake around his neck. John wore the locket with their hair inside it until his death. The locket was kept by one of Marshall’s children and eventually returned to the John Marshall House in Richmond, where it is today.

The Marshall House

John Marshall and some friends and relatives bought four lots that comprised a square or city block in the fashionable residential area of Richmond known as Court End. These properties, which included their homes, support buildings and gardens, were known as plantations-in-town. The Marshalls built a home on their square in 1790, which included their residence, a law office, laundry, kitchen, carriage house and stable, garden and carriage turn-around. John and Mary lived there for the rest of their lives.

Marshall loved his home in Richmond and spent as much time there as possible. His public duties in Washington, DC, and on circuit court in Virginia and North Carolina consumed an average of less than six months a year. So he was often with family and friends at their two-and-a-half-story brick house, which stands as a permanent memorial to John and Mary Marshall.

John was 35 years old, a successful lawyer and representative of Henrico County to the Virginia legislature. Mary was 24, a mother of four children, one of whom had died shortly after birth, and a trustworthy adviser to John. The house was both a domicile and a place of work.

Marshall’s public and private lives intertwined at home. He developed legal opinions, wrote public papers and greeted famous guests, and also served as father, husband and household manager. During the 1790s John Marshall became more and more involved in national politics. His pro-Federalist views were sharpened and deepened during this period when he spent much of his time at home.

Many of Marshall’s political allies also lived in the neighborhood, and some were invited regularly to monthly dinners at his house. These lawyers’ dinners included about 30 prominent men seated around the table in the large dining room or great hall at the center of the first floor. No women were invited to these dinners, which lasted from mid-afternoon until late evening. Marshall’s slaves prepared the food and served the guests. According to city tax records, Marshall owned 10 adult slaves in 1791.

Marshall in Politics

In 1782 Marshall moved from Fauquier County where he had been practicing law to Richmond where he served in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1782-1797. He was a member of the Council of State in 1782-1795 in Virginia. Marshall became known for his fairness, his belief in a strong federal government, and his acute intellect. These characteristics made him a leading member of the legal community in Richmond and prompted Federalist John Adams to call on Marshall to serve his country.

In 1797, President John Adams convinced John Marshall to serve as an envoy to France, along with Elbridge Gerry and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. Upon returning, Marshall was offered a seat on the Supreme Court by President Adams, but he declined, choosing instead to run for and was elected to the U. S. House of Representatives (1799). On May 12, 1800, Adams nominated Marshall to the post of Secretary of State, and he was confirmed unanimously by the Senate the next day.

Image: Chief Justice John Marshall in 1831

Henry Inman, Artist

On January 20, 1801, John Adams nominated Marshall to be Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, and the Senate confirmed the nomination unanimously on January 27. Marshall was sworn in on February 4, 1801, and he served in that position from January 1801 until his death in July 1835.

Marshall wrote to the president, “I hope never to give you occasion to regret having made this appointment.” In the years ahead, only Jefferson and his followers had any regrets, as they fumed about the chief justice’s nationalistic opinions in landmark Supreme Court cases. Whether in Washington, DC, or in Richmond, Marshall could not disengage from his vision of the U.S. Constitution.

Marshall brought unity and order to the Court by practically ending seriatim opinions (the writing of opinions by various justices). He influenced the Court’s majority to speak with one voice, through one opinion for the Court on each case before it. He clearly and convincingly argued that the Constitution is a permanent supreme law that the Supreme Court was established to interpret and defend.

His greatest opinions were masterworks of legal reasoning and graceful writing. They protected private property rights as a foundation of individual liberty. They also rejected claims of state sovereignty in favor of a federal Constitution based on the sovereignty of the people of the United States acting through a strong central government. They stand today as an authoritative commentary on the core principles of the U.S. Constitution.

The influence of his landmark decisions did much to strengthen the judicial branch of government and to define the tripartite arrangement that is so basic to the American system of government. Many scholars hold that Marshall was the founder of constitutional law and the expounder of the doctrine of judicial review. His decision in Marbury vs. Madison in 1803 declared the power of the Supreme Court to invalidate an act of Congress if that act was in conflict with the Constitution.

Marshall’s interpretation of the Constitution brought him into conflict with the Republican-Democrats, particularly President Thomas Jefferson. Although the two men were cousins, they were continually in conflict. Marshall believed that a strong federal government was necessary to ensure that the government would meet the needs of all the people. Jefferson, on the other hand, believed that the power of government should remain largely in the hands of the states.

In 1829, Marshall was a delegate to the Virginia constitutional convention, where he was joined by fellow American statesman and loyal Virginians, James Madison and James Monroe, although all were quite old by that time. Marshall mainly spoke at this convention to promote the necessity of an independent judiciary.

Mary Willis Ambler Marshall died December 25, 1831, at Richmond, Virginia, at the age of 65; she was buried at Shockoe Hill Cemetery, Richmond, VA. Most who knew John Marshall agreed that after Mary’s death, he was never quite the same.

John’s last written statement about Mary was penned at his home on December 25, 1832, exactly one year after her death:

This day of joy and festivity to the whole Christian world is to my sad heart the anniversary of the keenest affliction which humanity can sustain. While all around is gladness my mind dwells on the silent tomb, and cherishes the remembrance of the beloved object which it contains.

On the 25th of December 1831 it was the will of Heaven to take to itself the companion who had sweetened the choicest part of my life, had rendered toil a pleasure, had partaken of all my feelings and was enthroned in the inmost recesses of my heart. Never can I cease to feel the loss and to deplore it. Grief for her is too sacred ever to be profaned on this day, which shall be during my existence devoted to her memory.

On the 3rd of January 1783, I was united by the holiest bonds to the woman I adored. From the hour of our union to that of our separation I never ceased to thank Heaven for this its best gift. Not a moment passed in which I did not consider her as a blessing from which the chief happiness of my life was derived. This never dying sentiment, originating in love, was cherished by a long and close observation of as amiable and estimable qualities as ever adorned the female bosom.

I have lost her! And with her I have lost the solace of my life! Yet she remains still the companion of my retired hours – still occupies my inmost bosom. When I am alone and unemployed, my mind unceasingly turns to her.

On returning from Washington in 1835, Marshall was in a stagecoach accident, suffering severe injuries. His health, which had not been good, rapidly declined and in June he returned to Philadelphia for medical assistance. Two days before his death, he asked his friends to place only a plain slab over his and Mary’s graves.

John Marshall died on July 6, 1835, in Philadelphia at the age of 79, having served for 34 years. On July 8, while tolling for the funeral procession, the Liberty Bell cracked. Since then, the bell has been on display but has never been rung again. Marshall’s body was brought back to Richmond and laid next his beloved Polly in Shockoe Hill Cemetery.

The longest serving Chief Justice in Supreme Court history, Marshall was the second to last surviving Founding Father, the last being James Madison. His passing was mourned by the nation, but his legacy remains. He was one of the most influential leaders of his time – the era of the American Revolution and the establishment of the United States of America.

Image: Chief Justice John Marshall Monument

As a tribute to his judicial service a bronze statue stands on the lower west terrace of the Capitol in John Marshall Memorial Park, which is located on the site of a boarding house where Marshall and his fellow Supreme Court Justices drafted many of their landmark opinions. The statue represents the Chief Justice, sitting in his judicial robe, looking toward the Washington Monument, the memorial to a man he greatly admired.

SOURCES

The John Marshall House

Wikipedia: John Marshall

The John Marshall Foundation

NPS.gov: John Marshall at Home

NPS.gov: John Marshall on “My Dearest Polly”

The John Marshall Foundation: Video and Media

I used your wonderful blog as a memory document in the FamilySearch genealogy profiles of Mary Willis Ambler Marshall and her husband John. The citation lack an attribution to an author and date of publication. Are you willing to provide that information to me?

Citation: History of American Women is an online blog about Colonial Women of the 18th-19th Century Women and Civil War Women. The History of American Women Blog began after discovering that there was very little comprehensive information on the Internet about the brave and interesting women who lived in our nation’s past and who contributed in countless ways to the lives we enjoy today.

can you tell me the source of the name “Willis” in Mary’s name. It is a family name of mine.