Pioneer Women’s Rights Activist

Lucy Stone spoke out against slavery and for women’s rights at a time when it was not popular for women to speak in public, and she was the first woman to keep her maiden name after she was married. Her name is often overlooked in the history of the fight for women’s suffrage, but this trailblazer achieved several firsts for women, particularly in Massachusetts.

The Woman Question

In 1836, at age eighteen, Lucy Stone began noticing newspaper reports of a controversy that some referred to as the woman question. What was woman’s proper role in society? Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison asked to women to circulate antislavery petitions and send the signatures to Congress. Many women responded, which started a debate over whether women were entitled to a political voice.

In 1837, women abolitionists from seven states held a convention in New York City to expand their petitioning activities, declaring that they would no longer remain within limits prescribed by “corrupt custom and a perverted application of Scripture.”

Education

Lucy was determined to obtain the highest education possible; at the age of 21, she enrolled at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. She left after only one term because the founder Mary Lyon was intolerant of abolition and women’s rights. The following month Lucy enrolled at Wesleyan Academy, which she liked much better. She wrote to one of her brothers: “It was decided by a large majority in our literary society the other day that ladies ought to mingle in politics, go to Congress, etc.”

After a year at coeducational Monson Academy in the summer of 1841, Stone learned that Oberlin College in Ohio had become the first college in the nation to admit both women and African Americans. She enrolled at Quaboag Seminary in neighboring Warren to prepare for Oberlin’s entrance examinations.

In August 1843, just after she turned 25, Stone traveled by train, steamship, and stagecoach to study at Oberlin. In her third year there, she befriended Antoinette Brown, an abolitionist and suffragist who came to Oberlin in 1845 to study to become a minister. Stone and Brown eventually married two of the Blackwell brothers and became sisters-in-law.

Public Speaker

In the fall of 1846 Lucy Stone informed her family that she intended to become a women’s rights lecturer. Her father and brothers were supportive, but her mother and sister tried to dissuade her. Stone knew that she would be reviled, even hated by some.

Gaining public speaking experience proved to be difficult; therefore, Stone and Antoinette Brown organized an off-campus women’s debating club. Excerpt from an Oberlin page about Stone entitled “The first debating society”:

The young men had to hold debates as part of their work in rhetoric, and the young women were required to be present, for an hour and a half every week, in order to hlep form an audience for the boys, but were not allowed to take part. Lucy was intending to lecture and Antoinette [Brown] to preach.

Both [Stone and Brown] wished for practice in public speaking. They asked Professor Thome, the head of that department, to let them debate. He was a man of liberal views – a Southerner who had freed his slaves – and he consented. Tradition says that the debate was exceptionally brilliant. More persons than usual came in to listen, attracted by curiosity. But the Ladies’ Board immediately got busy, St. Paul was invoked, and the college authoritiues forbade any repitition of the experiment.

A few of the young women, led by Lucy, organized the first debating society ever formed among college girls. At first they held their meetings secretly in the woods, with sentinels on the watch to give warming of intruders. When the weather grew colder, Lucy asked an old colored woman who owned a small house, the mother of one of her colored pupils, to let them have the use of her parlor. At first she was doubtful, … but when she found that the debating society was made up of girls only, she decided that it must be an innocent affair, and gave her consent.

Her house was on the outskirts of the town, and the girls came one or two at a time, so as not to attract attention. Lucy opened the first formal meeting with the following statement:

“We shall leave this college with the reputation of a thorough collegiate course, yet not one of us has received any rhetorical or elocutionary training. Not one of us could state a question or argue it in successful debate. For this reason I have proposed the formation of this association.”

Lucy Stone received her baccalaureate degree from Oberlin College on August 25, 1847, becoming the first female college graduate from Massachusetts.

Women’s Rights Activist

Stone gave her first public speeches on women’s rights in the fall of 1847. Abby Kelley persuaded her to become a lecturing agent for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society in June 1848, stating that the experience would give her the speaking practice she still felt she needed before beginning her women’s rights campaign.

Stone proved to be an effective speaker; she was described as “a little meek-looking Quakerish body, with the sweetest, modest manners and yet as unshrinking and self-possessed as a loaded cannon.” In autumn 1848, she received an invitation to lecture for the women who had organized the Seneca Falls and Rochester women’s rights conventions earlier that summer.

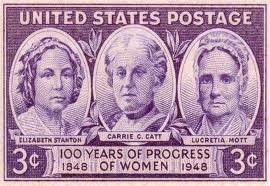

In April 1849, members the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society invited Stone to lecture for one of their events. While Stone was there, Lucretia Mott organized Pennsylvania’s first women’s rights meeting, on May 4, 1849.

With help from her abolitionist friends, Stone led Massachusetts’ first petition campaigns for the right of women to vote and hold public office. Wendell Phillips drafted the first petitions, and William Lloyd Garrison published them in his abolitionist newspaper Liberator for readers to copy and circulate. When Stone sent petitions to the legislature in February 1850, more than half were from communities where she had lectured. She also spoke in front of a number of legislative bodies to promote laws that gave more rights to women.

National Women’s Rights Convention

At the end of the New England Anti-Slavery Convention on May 30, 1850, an announcement was made that a meeting would be held to consider whether to hold a woman’s rights convention. At a large meeting that evening, William Lloyd Garrison said:

I conceive that the first thing to be done by the women of this country is to demand their political enfranchisement. Among the ‘self-evident truths’ announced in the Declaration of Independence is this: “All government derives its just power from the consent of the governed.”

The result of that meeting was the first National Women’s Rights Convention, held in October 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, which expanded into an annual series of meetings that brought the early women’s rights movement to the forefront. The Convention combined both male and female leadership and attracted supporters from other social reform movements. Speakers lectured about expanded education and career opportunities for women, equal wages, and marriage reform.

A second national convention was held October 15–16, 1851, with Paulina Wright Davis presiding. Harriet Kezia Hunt and Antoinette Brown gave speeches, and a letter from a Elizabeth Cady Stanton was read. Wendell Phillips made a speech which was so persuasive that it was sold as a pamphlet until 1920:

Throw open the doors of Congress; throw open those court-houses; throw wide open the doors of your colleges, and give to the sisters of the De Staels and the Martineaus the same opportunity for culture that men have, and let the results prove what their capacity and intellect really are. When woman has enjoyed for as many centuries as we have the aid of books, the discipline of life, and the stimulus of fame, it will be time to begin the discussion of these questions: “What is the intellect of woman? Is it equal to that of man?”

Lucy Stone helped organize the first eight meetings of the National Women’s Rights Convention, presided over the seventh, and was secretary of the Central Committee for most of the decade.

Courtship and Marriage

On October 14, 1853, Stone and Lucretia Mott addressed the first women’s rights meeting held in Cincinnati, Ohio, arranged by local businessman Henry Blackwell, and he was immediately smitten. Although Stone told him she did not wish to marry because she did not want to give up control of her life, Henry Blackwell began a two-year courtship of Stone in 1853.

Blackwell believed that marriage could allow each partner to accomplish more together than apart, and illustrated his ability to promote her work by scheduling her highly successful lecture tour of 1853 in the western states. Newspapers in several cities noted the popularity of her speeches. Elizabeth Cady Stanton later wrote that “Lucy Stone was the first speaker who really stirred the nation’s heart on the subject of woman’s wrongs.”

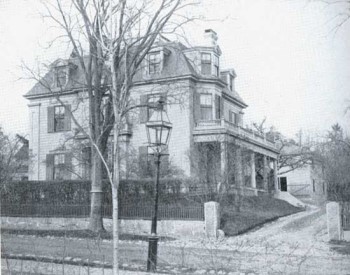

Image: Lucy Stone’s Home

West Brookfield, Massachusetts

During their courtship, conducted primarily through correspondence, Stone gradually fell in love and in November 1854 agreed to marry Blackwell. To calm Lucy’s misgivings, they drew up a private agreement that would protect her financial independence by hiring a trustee to control her assets.

They agreed to run the marriage like a business partnership. They would share their earnings and each could will their property to whomever they chose unless they had children. However, Lucy refused to be supported and insisted on paying half of their mutual expenses. Lucy and Henry also agreed that each would enjoy personal independence and autonomy:

Neither partner shall attempt to fix the residence, employment, or habits of the other, nor shall either partner feel bound to live together any longer than is agreeable to both.

Lucy Stone married Henry Blackwell May 1, 1855 at her home in West Brookfield, Massachusetts.

Protest Against Marriage Laws

When the two married, they registered the following protest, which Stone’s close friend Thomas Wentworth Higginson read at the ceremony:

While acknowledging our mutual affection by publicly assuming the relationship of husband and wife, yet in justice to ourselves and a great principle, we deem it a duty to declare that this act on our part implies no sanction of, nor promise of voluntary obedience to such of the present laws of marriage, as refuse to recognize the wife as an independent, rational being, while they confer upon the husband an injurious and unnatural superiority, investing him with legal powers which no honorable man would exercise, and which no man should possess. We protest especially against the laws which give to the husband:

1. The custody of the wife’s person.

2. The exclusive control and guardianship of their children.

3. The sole ownership of her personal, and use of her real estate, unless previously settled upon her, or placed in the hands of trustees, as in the case of minors, lunatics, and idiots.

4. The absolute right to the product of her industry.

5. Also against laws which give to the widower so much larger and more permanent interest in the property of his deceased wife, than they give to the widow in that of the deceased husband.

6. Finally, against the whole system by which “the legal existence of the wife is suspended during marriage,” so that in most States, she neither has a legal part in the choice of her residence, nor can she make a will, nor sue or be sued in her own name, nor inherit property.We believe that personal independence and equal human rights can never be forfeited, except for crime; that marriage should be an equal and permanent partnership, and so recognized by law; that until it is so recognized, married partners should provide against the radical injustice of present laws, by every means in their power.

The Protest was then published in newspapers across the country, and it inspired other couples to make similar protests part of their wedding ceremonies. Stone also kept her maiden name; she viewed the tradition of brides taking their husband’s surname as another measure in the legal annihilation of a married woman’s identity.

Henry and Lucy’s only child, Alice Stone Blackwell was delivered by Henry’s sister Dr. Emily Blackwell September 14, 1857. Alice would become a leader of the suffrage movement, and she wrote the first biography of her mother, Lucy Stone: Pioneer Woman Suffragist. In 1858, while the family was living temporarily in Chicago, Stone miscarried and they lost a baby boy.

Even after her marriage, Stone had continued a full work schedule of social reform activities, but the birth of her daughter in September 1857 made it impossible for her to maintain a high level of activism.

Taxation Without Representation

In the summer of 1857, Stone refused to pay her property tax bill because she was not fairly represented in government:

Sir: Enclosed, I return my tax bill, without paying it. My reason for doing so is that women suffer taxation, and yet have no representation, which is not only unjust to one half of the adult population, but is contrary to our theory of government. For years some women have been paying their taxes under protest but still taxes are imposed and representation is not granted. The only course now left us is to refuse to pay the tax.

On January 22, 1858, the city auctioned some of her household goods to pay the tax and attendant court costs.

Women’s Loyal National League

In 1863, Stone assisted in establishing the Women’s Loyal National League to help pass the Thirteenth Amendment and thereby abolish slavery. It was organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. In the largest petition drive in the nation’s history up to that time, the League presented nearly 400,000 signatures on petitions to abolish slavery to Congress.

The League was the first national women’s political organization in the United States. It marked a continuation of the shift of women’s activism to political action and a formally organized women’s movement and contributed to the development of a new generation of activists for the women’s movement.

In November 1869 she helped form the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), whose founders supported securing the right to vote for African American men before women. The AWSA also built support for a women’s suffrage Constitutional amendment by winning woman suffrage at the state and local levels.

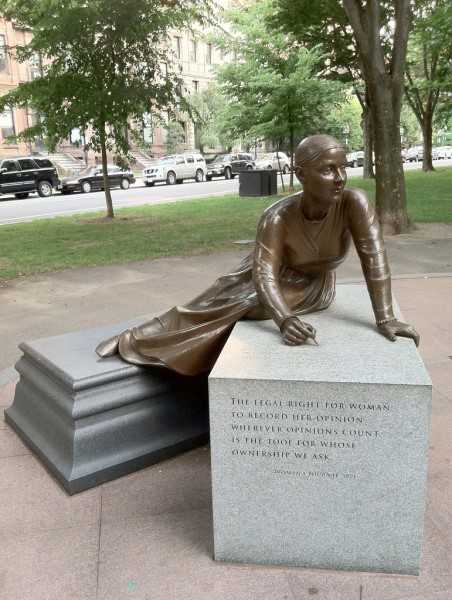

Boston Women’s Memorial

Lucy Stone did not live to see women achieve the right to vote. She died October 19, 1893. Even in death, she achieved two more firsts for women. She was the first person in Massachusetts to be cremated, and she had arranged to have six men and six women as pallbearers at her funeral.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote: “Lucy Stone was the first person by whom the heart of the American public was deeply stirred on the woman question.”

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Lucy Stone

Oberlin.edu: Lucy Stone (1818-1893)

Boston Women’s Heritage Trail: Lucy Stone

Wikipedia: National Women’s Rights Convention

Thank you for this informative article. I would offer a correction: the home pictured is, I believe, the one Lucy moved to in Dorchester, not the West Brookfield farm house she grew up in. The stone pillars at the end of the driveway (seen in the photo) still exist at the Dorchester site.