Writer, Philanthropist and Suffragist in Boston

Annie Adams Fields was a poet, philanthropist and social reformer, who wrote dozens of biographies of famous writers who were also her friends. She founded innovative charities to assist the poor residents of Boston and campaigned for the rights of women, particularly the right to vote and to earn a medical degree.

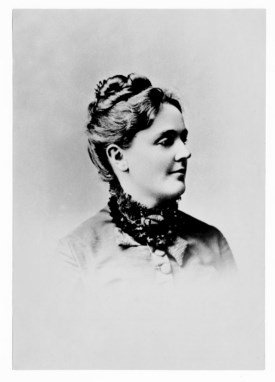

Image: Young Annie Adams Fields

Annie Adams was born June 6, 1834, the sixth of seven children of a wealthy family in Boston, Massachusetts. Her parents believed in progressive education for young women; as a girl, she attended a school in Boston that emphasized the classics and literature, which was run by George Emerson.

Marriage and Family

In 1854 Annie married James Thomas Fields, a partner with William Ticknor at Ticknor and Fields, the major publishing house in the United States during the mid-nineteenth century. Annie was his second wife. She was 20; he was 37. At a time when women married to establish a home and produce children, the Fields marriage appeared to be based on genuine love and respect. They had no children, possibly by choice.

In 1856, Annie and James moved into a new house at 148 Charles Street in Boston, where they would live out their days, and immediately began displaying their hospitality. In a typical week, they might host a dinner party and a reception, while also entertaining several houseguests. Author Henry James wrote of the Fields home:

Here, behind the effaced anonymous door was the little ark of the modern deluge, here still the long drawing-room that looks over the water and towards the sunset, with a seat for every visiting shade, from far-away Thackeray down, and relics and tokens so thick on its walls as to make it positively, in all the town, the votive temple to memory.

As a publisher, James Fields’ reputation rested on his ability to find talented writers, but his wife was even better at spotting promising authors. Annie Fields exerted a great deal of influence over her husband in the selection of works to be published by Ticknor and Fields. He valued her judgment, especially from a woman’s point of view. Together they discovered Emma Lazarus, Sarah Orne Jewett, Horatio Alger and Celia Thaxter. Annie was equally comfortable with great figures like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose biography Annie later wrote, Life and Letters of Harriet Beecher Stowe (1897).

Famous Friends

The Fieldses also regularly held a literary salon at their home, where the most famous writers gathered: Rudyard Kipling, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Henry James, Mark Twain and John Greenleaf Whittier, among others. Annie Adams Fields became a major figure in the cultural and social circles of Boston, hosting numerous parties whose guests were the most notable figures in both Boston and American society.

Annie was the epitome of the perfect hostess and society wife. The dinners and parties she hosted were attended by well-known authors, assuring their loyalty to her husband’s publishing house. She particularly encouraged women writers like Rebecca Harding Davis and Willa Cather. Speakers at the lectures and readings she held in her library included Nathaniel Hawthorne, the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher and Charles Dickens, who called her, “one of the dearest little women in the world.”

Philanthropy

In addition to her social activities, Annie established many charities to assist Boston’s poor. She also devoted her time to the abolitionist movement and campaigns to win the right to vote for women. The New England Women’s Club was one of many organizations she founded. She wrote How to Help the Poor, a guide for charities. She established the Holly Tree Inns, a series of nonprofit and inexpensive coffeehouses, and the Lincoln Street Home, a safe residence for unmarried working women.

Atlantic Monthly

One of the happiest years of the Fieldses’ life began when they sailed for England in June 1859. Another important event was William Ticknor’s acquisition of the Atlantic, a two-year-old “Magazine of Literature, Art, and Politics” that had gone bankrupt. When he returned from Europe, Fields immediately began increasing the magazine’s circulation by soliciting manuscripts from established as well as new writers. By the time Fields took over editorial duties from James Russell Lowell in the summer of 1861, the Atlantic had become the country’s premier literary periodical.

James Fields assumed responsibility for the entire magazine. The magazine’s influence soon extended beyond New England, as submissions and subscriptions arrived from New York, Ohio, and as far away as California. Just as she advised him on which books to accept for publication, Annie helped James choose which pieces to publish in the Atlantic from new authors. When essays or serial novels from the Atlantic were published in book form, earnings increased dramatically, for both author and publisher.

William Ticknor died unexpectedly in the spring of 1864, resulting in major changes in the firm. James Fields moved into larger quarters in a building overlooking Boston Common and purchased three more magazines: Our Young Folks, North American Review and Every Saturday.

In 1868, after James Fields changed her royalty payments from a percentage to a unit rate, popular essayist Gail Hamilton accused Fields of cheating her. She also convinced Sophia Hawthorne, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s widow, that Fields had bilked her. Hamilton spread the word by publishing The Battle of the Books (1870), a thinly disguised attack on him. Although he was guilty of no wrongdoing, Fields’ reputation was stained, and he retired from publishing in 1870.

James continued to write for the Atlantic and other periodicals. The essays he wrote about writers he had known appeared first in the Atlantic and were then published in book form, entitled Yesterdays with Authors. He also became a very popular lecturer.

James T. Fields – foremost publisher of literature and one of the greatest magazine editors in the mid-nineteenth century – died April 24, 1881 at their Charles Street home.

Image: Sarah Orne Jewett

Romantic Friendship

When James Fields died in 1881, Annie turned for solace to the woman who had become her closest friend, novelist and story writer Sarah Orne Jewett, whose works James had published in the Atlantic. When Annie began spending time with the young lady from Berwick, Maine, Jewett was just another up-and-coming woman writer.

However, their relationship soon had positive effects on the creativity of both women. As Annie exercised her own desire to be a writer, she relied on Sarah for assistance and encouragement. While Sarah was a better writer, Annie exerted great influence in the Boston literary world. Their partnership seems to have allowed them both to pursue individual careers, free of the restrictions society placed on women in 19th-century America. Fields no longer had to negotiate between the needs of her husband’s career and her own; nor were there children in the picture.

Historian Caroll Smith-Rosenberg characterizes the relationship between Jewett and Fields as a romantic friendship, which developed in response to a Victorian culture that segregated men and women both emotionally and physically. In her research, Rosenberg discovered that women in this era engaged in a variety of relationships with other women, which “ranged from the supportive love of sisters through the enthusiasms of adolescent avowals of love by mature women.”

For a time, contemporary society did not view the romantic friendship that developed between Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett as abnormal or perverse, but as a natural female relationship. Before long, Jewett moved into 148 Charles Street, where she spent winters for the rest of her life; the couple also spent time at the Jewett home in South Berwick, Maine. Fields and Jewett lived together for the rest of Jewett’s life.

Boston Marriage

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the term Boston marriage was coined to describe a relationship between widows or unmarried women that were common in that city, although such arrangements existed in other areas of the country. The term applied to two women living together, independent of support from a man. Some women deliberately chose not to marry because they had a stronger connection to women than to men. Those who chose to live together were usually financially independent.

Women who chose to have a career (doctor, scientist, professor) created a new class of women who were not dependent upon men. Nor was marriage an attractive lifestyle to these independent women. For a time, educated women who chose to have careers and to live with other women, they were sometimes allowed a measure of social acceptance. These women were most often self-sufficient in their own lives but gravitated to each other for support in a society that could sometimes be hostile to career women.

In her book Surpassing the Love of Men, Lillian Faderman describes the Jewett-Fields relationship as an example of a Boston Marriage:

[Two women who] are generally financially independent of men, either through inheritance or because of a career. They were usually feminists, New Women, often pioneers in a profession. They were also very involved in culture and in social betterment, and these female values, which they shared with each other, formed a strong basis for their life together.

In addition to supporting one another emotionally, Fields and Jewett surrounded themselves with other powerful women, like Elizabeth Cary Agassiz, founder of Radcliffe College, and Bryn Mawr’s M. Carey Thomas. They also supported nationally known Associated Charities and the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Nor were Jewett and Fields alone in their lifestyle; many of their female friends lived in such arrangements with other women. Annie’s sister, painter Lissie Adams, kept a house with a Miss Burnap in Baltimore; artist Anne Whitney lived with Olive Dargan; Alice James lived with Katherine Loring; actress Charlotte Cushman set up a household with sculptor Emma Stebbins. They also forged friendships as a couple with male literary figures like Charles Dudley Warner and John Greenleaf Whittier.

Literary Career

Annie Adams Fields was a multi-talented woman who encouraged the talents of others. Although she was known for her poetry back then, today she is remembered for the important collections of letters she edited and the short sympathetic biographical sketches she wrote later in life. Her book Authors and Friends (1896) is a series of such biographies. She chose her subjects carefully: Oliver Wendell Holmes, John Greenleaf Whittier and Celia Thaxter. She also edited a collection of Sarah Orne Jewett’s letters.

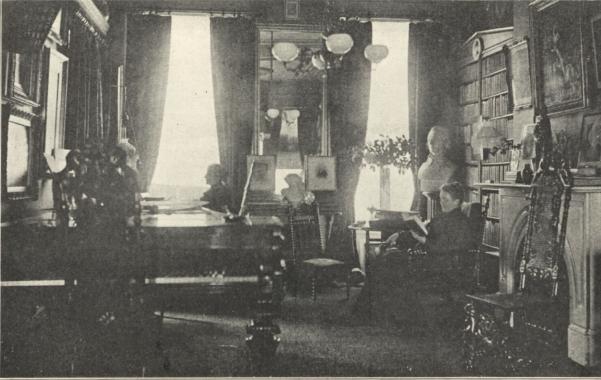

Image: Annie Fields and Sarah Jewett

In the drawing room at the Fields home

148 Charles Street, Boston

While living with Jewett, Annie Adams Fields, who had spent her early years nurturing and promoting other writers, became herself a prolific and accomplished author. She produced two books of her own poetry, Under the Olive (1880) and The Singing Shepherd and Other Poems (1895); James T. Fields: Biographical Notes and Personal Sketches (1882); and two plays. She also continued her work on behalf of charity and the suffragist movement.

On her fifty-third birthday in 1902, Sarah Orne Jewett fell from a carriage and suffered permanent injuries to her head and spine, ending her writing career. Jewett was paralyzed by a stroke in March 1909, and she died on June 24, 1909 after suffering another.

Since James Fields’ death, Annie had always worn black or purple clothing, the traditional colors of mourning, and sometimes a mourning veil as well. After Jewett’s death she continued to wear widow’s weeds.

Annie Adams Fields died January 5, 1915 at the age of 80.

SOURCES:

Andrey Koymasky: Annie Adams-Fields

Wikipedia: Boston Marriage

Wikipedia: Annie Adams Fields

Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Adams Fields

Will the Real Annie Adams Fields Please Stand Up?

American National Biography: James Thomas Fields