Wife of Declaration of Independence Signer: Stephen Hopkins

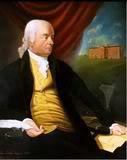

Image: Stephen Hopkins

By John Hagen

Sarah Scott was born on June 24, 1707, the daughter of Silvanus and Joanna Jenckes Scott, and a great-granddaughter of Richard Scott, said to be the first Quaker in Rhode Island. Richard Scott’s wife was Catharine Marbury, sister of Anne Marbury Hutchinson, who was driven from Boston during the period of religious intolerance in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the seventeenth century.

Stephen Hopkins was born in Providence on March 7, 1707, in Cranston, Rhode Island, the son of William and Ruth (Wilkinson) Hopkins. He was descended from the Thomas Hopkins who emigrated to Plymouth Plantation in 1635, and he was raised in his mother’s Quaker religion. He grew up in the small agricultural community of Scituate, west of Providence, RI. He was reared to be a farmer, and had inherited his father’s estate in Scituate, but he was chiefly employed as a land surveyor.

Sarah Scott married Stephen Hopkins on October 9, 1726. Both were Quakers, and both were nineteen years old. To create a home and support for the newlyweds, Stephen’s father gave them seventy acres of land, and his grandfather, Thomas Hopkins, bestowed upon his “loving grandson,” as the will reads, an additional grant of ninety acres.

There is little information about Sarah Scott Hopkins, except that it is recorded that she was “a kindly, industrious, and frugal woman, a good mother and an affectionate wife.” She was the mother of seven children, only five of whom arrived at maturity: Rufus, John, Lydia, Silvanus, and George.

Stephen Hopkins began his life of public service in Scituate in 1730, when he was chosen Town Moderator at the age of 23. During the next decade, he held the following offices: town clerk, president of the town council, town solicitor, justice of the peace, justice and clerk of the Providence County Court of Common Pleas (in 1733, he became Chief Justice of that court), Representative from Scituate to the General Assembly of Rhode Island (1732-1752), and Speaker of the House (1738-1744 and 1749). He traveled a considerable distance to the General Assembly in Newport, 30 miles South of Scituate.

In 1742, Hopkins sold of his father’s estate in Scituate, and moved to Providence, where he made a survey of the streets and lots. Under his leadership Providence paved the streets and built bridges, wharves, and storehouses, and grew rapidly into an economic power.

Along with his equally famous brother Esek, Stephen Hopkins bought a store in Providence that led to a successful and profitable career in a mercantile and ship-building partnership. For three decades, he built up his business and would probably have acquired a fortune had he not at the same time supported a variety of civic enterprises and broadened his political activities.

In 1751, Stephen Hopkins was chosen Chief Justice of the Superior Court, a position he held until 1754. He also helped set up a public subscription library in Providence in the 1750s, and cataloged its first collection. He helped found the influential newspaper Providence Gazette and Country Journal in 1762.

Two of the Hopkins’ sons – John and Silvanus – died in 1753. John, who was master of the ship Two Brothers, died of small-pox off the coast of Spain at the age of 24. The ship immediately put into port, but because he was a Protestant, John was denied a Christian burial. Silvanus sailed for Cape Breton, as mate of a small schooner, and on his return was wrecked off the coast of Nova Scotia. In attempting to return to Louisburg in an open boat, he was surprised by Indians on the shore of St. Peter’s Island, and his body left on the beach.

Sarah Scott Hopkins also died in 1753.

At the Albany Congress (1754), Hopkins cultivated a friendship with Benjamin Franklin and assisted him in lobbying for a plan of colonial union, and arranging for an alliance with the Indians, in view of the impending war with France. Hopkins wrote A True Representation of the Plan Formed at Albany (1755) in hopes of converting the opposition in Rhode Island.

Stephen Hopkins married Ann Smith (1717-1782) in 1755, her second marriage also.

In 1756, Hopkins was elected Governor of the colony, and he held that office for nine one-year terms, as he and Samuel Ward played musical chairs with the Governorship. These annual battles for the Governor’s office took on a farcical air, with Hopkins supporters, John and Moses Brown, buying up votes; the Ward camp did likewise. This period was one of bitter strife in the colony between Newport and Providence, with Hopkins leading the Providence faction.

While he was Governor, Hopkins had a disagreement with William Pitt, Prime Minister of England, regarding illegal molasses trade with the French colonies. Hopkins was one of the earliest and most vigorous champions of colonial rights.

In 1764, Stephen Hopkins penned The Rights of Colonies Examined, published first in the Providence Gazette. It was also printed as a pamphlet, and reissued in London in 1766 as The Grievances of the American Colonies Candidly Examined. This famous work criticized parliamentary taxation (the Stamp Act) and recommended colonial home rule, and established Hopkins as one of the earliest patriot leaders.

He acted as first chancellor of Rhode Island College (later Brown University), founded in 1764 at Warren, and six years later he was instrumental in relocating it to Providence, and served as its chancellor until 1785. He also held membership in the Philosophical Society of Newport.

In 1765, Hopkins was elected chairman of the committee appointed by a town meeting in Providence to draft instructions to the General Assembly on The Stamp Act. In 1770, Hopkins was appointed to a Providence Committee of Inspection, a group that attempted to enforce the agreements of nonimportation of British goods among area merchants.

The Gaspee Affair

Molasses was very important to the prospering colony; the British should have realized that any restrictions on its import would lead to trouble and rebellion. Parliament had passed a Molasses Act in 1733, imposing a duty on molasses bought at ports that were not British-owned, but it was not strictly enforced, and the shipping companies knew of ways to avert the customs officials in the harbor.

Enforcement of the act was so lax that Rhode Islanders got away with importing five-sixths of the molasses they used from French, Spanish, and Dutch islands. Then in the 1760s, Parliament took measures toward greater control over the colonies and passed a series of acts, the first of which was the Sugar Act of 1764.

Duties on molasses not from the British West Indies would be strictly enforced, and the ships that now patrolled Narragansett Bay proved how unrelenting the officials could be. Rhode Islanders resented the revenue ships, the searching of their vessels, and the stupidity of the measure. The British knew that their islands in the West Indies could not produce enough molasses to supply the colonies.

Captain William Dudingston was very unpopular with the colonists; he had been inspecting even the small boats that transported goods between ports in the Bay. His British revenue schooner, the Gaspee, was chasing the sloop Hannah in order to search her for smuggled goods, when it was lured too close to shore by the Hannah’s captain and ran aground on the western shore of Narragansett Bay. The Gaspee would have to wait until morning for the tide to free her.

On June 9, 1772, a band of Providence members of the Sons of Liberty rowed out to confront the officers and crew before the rising tide could free her. At the break of dawn June 10, a small party of men boarded the ship. Captain Dudingston was wounded – the first Englishman to shed blood in the American Revolution. The sleepy crew was rounded up and put ashore, and the Gaspee was burned to the waterline.

The Sons of Liberty was a secret organization of American Patriots. British authorities and their supporters – known as Loyalists – considered the Sons of Liberty seditious rebels, referring to them as Sons of Violence and Sons of Iniquity. Patriots attacked the symbols of British authority and power such as property of the gentry, customs officers, East India Company tea, and as the war approached, vocal supporters of the Crown.)

Stephen Hopkins gave immediate advice to help limit Royal reprisals. As Chief Justice of the Superior Court, he declared that the Rhode Island courts would not cooperate with the Gaspee investigatory commission, and refused to hand over any citizen to the British Admiralty. He managed to stymie British officials in their pursuit of the arsonists, and his refusal to comply with British demands made sure that none of the 40 or so men were ever tried.

The names of the men who had rowed out to the ship so soundlessly that night, though well known in Providence, were kept secret until after the American Revolution, and no one ever claimed the large reward offered by the British for information leading to their capture. The incident was one of the most prominent colonial acts of defiance in the troubled years before independence.

Image: Stephen Hopkins House

In 1743, Stephen Hopkins purchased this 1708 home in Providence, Rhode Island, and attached to it his own two-story house, built with a single ground floor room on either side of a central hallway and two chimneys (one for each main floor room with chamber above). He resided in this home until his death, and George Washington is said to have slept there on April 5, 1776.

In March 1773, the Virginia House of Burgesses, in response to the threats to American liberties posed by the Gaspee Affair, created the first permanent intercolonial Committee of Correspondence. Peyton Randolph, Speaker of the Virginia House, sent these resolutions to Rhode Island to be laid before the General Assembly at the May session. The Assembly adopted resolutions creating a committee of correspondence for Rhode Island.

In 1773, in keeping with the directives of Quaker leadership at the time, Hopkins freed the slaves he had acquired through marriage. In 1774, again elected to the General Assembly, he authored a bill enacted by the Rhode Island legislature that prohibited the importation of slaves into the colony – one of the earliest antislavery laws in America.

Stephen Hopkins on Slavery:

The whole of our war with Britain was a contest for Liberty: By which we, when brought to the severest test, practically adhered to the above assertions, so far as they concerned ourselves, at least, and we declared, in words and actions, that we chose rather to die than to be slaves, or have our liberty and property taken from us. We viewed the British in an odious and contemptible light, purely because they were attempting, by violence, to deprive us, in some measure, of those our unalienable rights.

But if at the same time, or since we have taken or withheld these same rights from the Africans, or any of our fellow men, we have justified the inhabitant of Britain in all they have done against us, and declared that all the blood which has been shed in consequence of our opposition to them, is chargeable on us.

If we do not allow this, and abide by the above declarations, we charge ourselves with the guilt of all the blood which has been shed by means of the slave trade; and of an unprovoked and most injurious conduct in depriving innumerable Africans of their just, unalienable rights, in violently taking and withholding from them all liberty and property; holding them as our own property, and buying and selling them, as we do our horses, and cattle; reducing them to the most vile, humiliating, and painful situation.

~Friends of the Constitution: Writings of the ‘Other’ Federalists, 1787-1788

Edited by Colleen A. Sheehan and Gary L. McDowell

Hopkins was elected to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia in August 1774, “to represent the people of this colony in a general congress of representatives from the other colonies, at such time and place as shall be agreed upon by the major part of the committees appointed or to be appointed by the colonies in general.” These were the first delegates from any colony elected to the Congress of 1774.

While at Congress, Hopkins served on the committees that prepared the Articles of Confederation, and his knowledge of the shipping business made him particularly useful as a member of the Naval Committee. He had persuaded the Congress in 1775 to outfit thirteen armed vessels and to commission them as the Navy of the United Colonies. He also saw to it that Rhode Island received a contract to outfit two of these, and appointed his brother Esek Hopkins as its commander-in-chief.

When Rhode Island became the first colony to renounce its allegiance to King George III, in effect declaring its independence on May 4, 1776, Hopkins wrote:

I observe that you have avoided giving me a direct answer to my queries concerning independence; however, the copy of the act of the Assembly, which you have sent me, together with our instructions, leave me little room to doubt what is the opinion of the colony I came from.

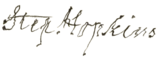

In 1776, at the age of 69 – the second oldest next to Benjamin Franklin – Stephen Hopkins had the honor of signing the Declaration of Independence, which declared the colonies to be free, sovereign, and independent states. In his later years, Hopkins had a shaking palsy, what was probably Parkinson’s Disease, and had to use his left hand to guide his right as he signed. As he signed the Declaration, he said: “My hand trembles, my heart does not.”

Image: Stephen Hopkins’ Signature

The signing of the Declaration of Independence by most of the fifty-six members of the Continental Congress did not actually take place until August 2, 1776. Under British law, the signing of such a document was considered an act of treason against the Crown. The men involved all knew they were putting their lives on the line, and that if things went badly for the colonies, they would most likely be executed. As Benjamin Franklin put it: “We must indeed all hang together, or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.”

Hopkins has been quoted as stating decisively that the time had come “when the strongest arm and the longest sword must decide the contest, and those members who were not prepared for action had better go home.” He distinguished himself as a bold orator in the Continental Congress. “The liberties of America would be a cheap purchase with the loss of but 100,000 lives,” he confessed to a colleague.

Fellow statesman John Adams was impressed with Hopkins. From David McCullough’s John Adams:

Knowing nothing of armed ships, he (Adams) made himself expert, and would call his work on the naval committee the pleasantest part of his labors, in part because it brought him in contact with one of the singular figures in Congress, Stephen Hopkins of Rhode Island, who was nearly as old as Franklin, and always wore his broad-brimmed Quaker hat in chamber.

In September 1776, continued ill health compelled Hopkins to resign from the Continental Congress and return to his home in Rhode Island. He declined subsequent reelections to Congress, but from 1777 to 1779, he remained an active member of Rhode Island’s general assembly, and took part in several New England political conventions.

He completely withdrew from public service about 1780. His second wife Ann Smith Hopkins died in 1782.

Stephen Hopkins died on July 13, 1785, in Providence, at the age of 78. He was interred in the Old North Burial Ground, where both of his wives had preceded him. It is said he retained full possession of his faculties to the end.

Details of his funeral procession and eulogy were published in the Providence newspapers: “A vast assemblage of persons, consisting of judges of the courts, the president, professors and students of the college, together with the citizens of the town, and inhabitants of the state, followed the remains of this eminent man to his resting place in the grave.”

SOURCES

Stephen Hopkins

Sarah Scott Hopkins

Grave of Stephen Hopkins

Wikipedia: Stephen Hopkins

Joseph Wilkinson and the Hopkins Family

Governor (and Chief Justice) Stephen Hopkins