Second Wife of Patriot Samuel Adams

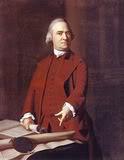

Image: Samuel Adams

John Singleton Copley, Artist

Samuel Adams was an American statesman, politician, writer, and political philosopher, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. Adams was instrumental in garnering the support of the colonies for rebellion against Great Britain, eventually resulting in the American Revolution, and was also one of the key architects of the principles of American republicanism that shaped American political culture. Samuel Adams is sometimes called the Father of the American Revolution, because of his early stand against the tyranny of Great Britain, and his speeches and writings that drew many American colonists into the fight for freedom.

Samuel Adams was born September 27, 1722, in Boston to Mary Fifield and Samuel Adams, Sr, their tenth child. He attended Boston Latin School, and received bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Harvard University. In 1748, his father died, and Sam Adams, as he was called, inherited the family brewery and a sizable estate. Within ten years, he had spent and mismanaged most of it, to the point where creditors attempted to seize his home. By 1760, Adams was bankrupt and working as a Boston tax collector.

After a few years of courtship, Samuel Adams married Elizabeth Checkley on October 17, 1749. In September of the following year, Elizabeth gave birth to a son named Samuel, but the infant died only eighteen days after birth. On October 16, 1751, Elizabeth again gave birth to a son they also named Samuel. Fortunately, there were no health issues with the child. Another son named Joseph was born just two years later, but he died the following day. Exactly a year after Joseph’s birth, Elizabeth gave birth to the couple’s first daughter, Mary. Mary lived for only three months and nine days. Another daughter, Hannah, was born eighteen months later, and stayed healthy. Only Samuel and Hannah survived to adulthood.

After giving birth to a stillborn son, Elizabeth Checkley Adams died on July 25, 1757 at the age of thirty-two. After this date Samuel wrote in the family Bible:

To her husband she was as sincere a friend as she was a faithful wife. Her exact economy in all her relative capacities, her kindred on his side as well as her own admire. She ran her Christian race with remarkable steadiness and finished in triumph! She left two small children. God grant they may inherit her graces!

On December 6, 1764, forty-two-year-old Samuel Adams married Elizabeth Wells, the twenty-nine-year-old daughter of his good friend, Francis Wells, an English merchant who came to Boston with his family in 1723. They had no children, but Elizabeth helped raise Samuel and Hannah, the surviving children of the first Mrs. Adams.

Elizabeth Wells Adams was a pleasant and hard-working woman who, through the forty years of life that remained to Sam, supported him in every way. She turned out to be a good manager. While he nurtured the birth of Independence, he was quite careless about his home and the condition of his own children’s clothes and shoes.

Sam Adams was not a successful man according to the standards of his neighbors, though looked upon as one of strict integrity and morality. He wasn’t good at making money and, and he seemed to have no desire to accumulate property. More than once the family would have become objects of charity if not for his wife. His hair was already turning gray, and a peculiar tremble of the head and hands made him appear old, but his health was remarkably good.

His father had left him a fairly profitable malting business, a comfortable house on Purchase Street, and 1000 pounds in money. Half the money he had loaned to a friend who never repaid him. The malt business was neglected and mismanaged, so it did not pay expenses. Sam Adams was always talking politics, writing newspaper articles, debating before the town meeting, or framing up some act for the Assembly to strengthen the rights of the people. This is where his talents lay.

He remained as poor as ever. He was a tax collector for years. Times were hard, money woefully scarce, and the collections became sadly in arrears. Then it came out that Sam Adams had refused to sell out the last cow or pig or the last sack of potatoes or corn meal or the scant furniture of a poor man to secure his taxes. He had told his superiors that the town did not need the taxes as badly as most of these poor people needed their belongings, and that he would rather lose his office than force such collections. He had connected with the plain people of Boston, who would be ready to elect him to any office that he would accept.

As an influential member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives and the Boston Town Meeting in the 1760s, Sam was a part of a movement opposed to the British Parliament’s efforts to tax the American Colonies without their consent. By 1765, he was drafting protests against the Stamp Act that protested British efforts to tax the colonists.

Adams’s next move was to protest the Townshend Acts of 1767, which placed customs duties on imported goods. His stand placed him in the front ranks of the leading colonists, and gained him the hatred of both British General Thomas Gage and England’s King George III. To protest the Townshend Acts, Adams and other radicals called for an economic boycott of British goods. Though the actual success of the boycott was limited, Adams had proved that an organized minority could effectively combat a larger but more disorganized group.

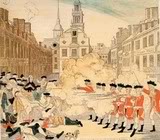

Image: The Boston Massacre

Engraving by Paul Revere

While a member of the legislature, as clerk of the house, Sam was responsible for drafting written protests of various British governmental acts. In February 1768, he drafted the Massachusetts Circular Letter as a response to the Townshend Acts, which was distributed among the other colonies in an effort to achieve a united front of resistance. King George III demanded that the contents of this letter be rescinded, but the legislature refused, which resulted in the stationing of British troops in Boston in 1768. The British troop presence in Boston, aggravated by protests such as Adams’ formation of the Non-Importation Association, led to the Boston Massacre (a term coined by Adams) in 1770.

Writing of Adams in 1769, biographer James Hosmer wrote:

For years now, Samuel Adams had laid aside all pretence of private business and was devoted simply and solely to public affairs. The house on Purchase Street still afforded the family a home. His sole source of income was the small salary (one hundred pounds) he received as clerk of the Assembly. His wife, like himself, was contented with poverty; through good management, in spite of their narrow means, a comfortable home life was maintained in which the children grew up happy and in every way well trained and cared for.

John Adams tells of a drive taken by these two kinsmen on a beautiful June day, not far from this time, in the neighborhood of Boston. Then as from the first and ever after there was an affectionate intimacy between them. They often called one another brother, though the relationship was only that of second cousin. ‘My brother, Samuel Adams, says he never looked forward in his life; never planned, laid a scheme, or formed a design of laying up anything for himself or others after him.’ The case of Samuel Adams is almost without a parallel as an instance of enthusiastic, unswerving devotion to public service throughout a long life.

Elizabeth was doing needlework and kitchen gardening to eke out the scant allowance she had to furnish a livelihood for herself and family. Yet there is no evidence that she complained – no chiding because of Sam’s waste of time and talent working for other people without compensation and neglecting his own affairs and family. She and his children seemed to think that whatever he thought or whatever he did must be right.

To help coordinate resistance to what he saw as the British government’s attempts to violate the British Constitution at the expense of the colonies, in 1772 Sam Adams and his colleagues devised a committee of correspondence system, which linked Patriots throughout the Thirteen Colonies. Continued opposition to British policy resulted in the coming of the American Revolution.

Sam Adams is best remembered for helping organize the Boston Tea Party, in response to the Tea Act passed by Parliament on May 1773. The intention of this law was to prop up the East India Company, which was floundering financially and burdened with eighteen million pounds of unsold tea. This tea was to be shipped directly to the colonies, and sold at a bargain price, which would have undercut the business of local merchants.

Colonists in Philadelphia and New York turned the tea ships back to Britain. In Boston, the Royal Governor held the ships in port, where the colonists would not allow them to unload. Cargoes of tea filled the harbor, and the British ship’s crews were stalled in Boston looking for work and often finding trouble. This situation lead to the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773.

The British were shocked by the destruction of the tea in Boston Harbor and other colonial protests, which they believed were clearly undermining their authority in the colonies. The Parliament passed a series of laws called the Coercive Acts, and known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts. These acts included the closing of the port of Boston, until the East India Company received compensation for the tea dumped into the harbor. The Royal governor took control of the Massachusetts government.

The Coercive Acts succeeded in uniting the colonies to take action against the Crown. The angry reaction from all the colonies was to expedite the opening of a Continental Congress, and when the Massachusetts legislature met in Salem, Adams locked the doors and made a motion for the formation of a colonial delegation to attend the Congress. A loyalist member, faking illness, was excused from the assembly and went immediately to the governor, who issued a writ for the legislature’s dissolution; but when the legislator returned to find a locked door, he could do nothing.

Sam Adams was one of the major proponents of the Suffolk Resolves, which called for disobedience to the Coercive Acts, endorsed military preparations for defense, and called for the meeting of a provincial congress. Adams opposed a compromise and advocated boycotts of British imports.

In September 1774, he left the legislature and was a delegate to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. He was at the head of several committees devoted to the relief of Boston. Because of the closing of the port, the city was in bad circumstances. Donations were coming from far and near and were distributed by one of the committees of which Adams was chairman. Another of his committees laid out public works, opening streets and wharves, and furnishing work for many citizens.

In the series of events in Massachusetts that led up to the first battles of the Revolution, Sam Adams wrote dozens of newspaper articles that stirred his readers’ anger at the British. He appealed to American radicals and communicated with leaders in other colonies. In a sense, Adams was burning himself out. By the time of the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts on April 18, 1775, which marked the beginning of the Revolutionary War, his career as a revolutionary leader had peaked.

Sam was one of the first and loudest voices for independence, and was a workhorse member of the Second Continental Congress beginning in May 1775, serving on numerous committees. He served in the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1781, but after the first session his activities lessened and his ties to other leaders cooled. He was uncertain about America’s next steps and where he would fit into the scheme.

Letter from Samuel to Elizabeth Adams:

Philadelphia, June 28, 1775:

My Dearest Betsy,

Yesterday I received Letters from some of our Friends at the Camp informing me of the Engagement between the American troops and the Rebel Army at Charlestown. I cannot but be greatly rejoiced at the tried Valor of our Countrymen, who by all Accounts behaved with an intrepidity becoming those who fought for their Liberties against the mercenary Soldiers of a Tyrant.It is painful to me to reflect on the Terror I suppose you were under, on hearing the Noise of War so near. Favor me, my dear, with an Account of your Apprehensions at that time, under your own hand. I pray God to cover the heads of our Countrymen in every day of Battle, and ever to protect you from Injury in these distracted times.

The Death of our truly amiable and worthy Friend Dr. [Joseph] Warren is greatly afflicting; the language of Friendship is, how shall we resign him; but it is our Duty to submit to the Dispensations of Heaven ‘whose ways are ever gracious and just.’ He fell in the glorious Struggle for public Liberty.

Remember me to my dear Hannah and sister Polly and to all Friends… [General Thomas] Gage has made me respectable by naming me first among those who are to receive no favor from him. I thoroughly despise him and his proclamation… The Clock is now striking twelve. I therefore wish you good Night.

Yours most affectionately,

S. ADAMS

Letter from Elizabeth to Samuel Adams:

Cambridge, 1775

MY DEAR,

I received your affectionate Letter by Fesenton, and I thank you for your kind Concern for my Health and Safety. I beg you Would not give yourself any pain on our being so Near the Camp; the place I am in is so Situated that if the Regulars should ever take Prospect Hill, which God forbid, I should be able to make an Escape, as I am Within a few stones casts of a Back Road, Which Leads to the Most Retired part of Newtown…I beg you to Excuse the very poor Writing as My paper is Bad and my pen made with Scissors. I should be glad (My dear), if you shouldn’t come down soon, you would Write me Word Who to apply to for some Money, for I am low in Cash and Everything is very dear.

May I subscribe myself yours,

ELIZAH ADAMS

Early in August 1775, Samuel Adams and the other delegates from Massachusetts hurried home to their families. Congress had adjourned from August 1 until September 5, and when Adams arrived from Philadelphia, he found the General Assembly of the Territory of Massachusetts Bay in session and himself entitled to sit as one of the eighteen councilors. The delegation was in charge of $500,000 for the use of General Washington’s army. Samuel Adams was at once elected Secretary of State.

Elizabeth Adams, who had been forced to leave Boston, was living with her daughter at the home of her aged father in Cambridge, and Samuel Adams, Jr. held an appointment as surgeon in Washington’s army. Friends were looking after all of them. Mr. Adams’s visit with his family was a short one, and on September I2, he started on his return to Philadelphia, on a horse loaned him by John Adams.

The coming years of Elizabeth’s life brought more of peace and comfort than during the Revolution or the years leading up to it. After the British evacuated Boston in March 1776, she and her family returned to the city to live. Sometimes they were “low in cash,” as she naively put it, but with her fine sewing and Hannah’s “exquisite embroidery,” they managed to live in comfort.

The climax of Sam’s political career came when he signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776. After that, Adams, wary of a strong central government, was instrumental in the development and adoption of the loose government embodied in the Articles of Confederation, which he also signed in 1777.

Samuel Adams retired from Congress in 1781 and returned to Boston, but was constantly in office in Massachusetts. He was elected to the state senate of Massachusetts, and served in that body until 1788, becoming its president.

At the time of the drafting of the United States Constitution, Adams was considered an anti-federalist, but more moderate than others. His contemporaries nicknamed him “the last Puritan” for his views. He finally came in on the side of ratification, with the stipulation that a Bill of Rights be added.

Dr. Samuel Adams, Jr. died in 1788, only in his late thirties. He had studied medicine under Dr. Joseph Warren, friend and fellow patriot. The younger Adams had served as surgeon in General George Washington’s army during the Revolutionary War, but had fallen ill and never fully recovered. The death was a stunning blow to the elder Adams, but there was joy in the happy marriage of his daughter Hannah to Captain Thomas Wells, a younger brother of Elizabeth Adams.

In 1794, Sam Adams was elected Governor of Massachusetts, but he retired from politics at the end of his term in 1797. He suffered from what is now believed to have been essential tremor, a movement disorder that rendered him unable to write during the final decade of his life. His daughter Hannah had to sign his name for him.

Upon his death, young Sam had left the certificates he had earned as a soldier – about $6000 – giving Sam and Elizabeth unexpected financial security in their final years. Investments in land would make them relatively wealthy by the mid-1790s, but this did not alter the frugal lifestyle of the old patriot and his wife.

Image: Samuel Adams Statue

Anne Whitney, Sculptor

The bronze statue in front of Faneuil Hall portrays the Revolutionary patriot just after he demanded that Governor Hutchinson immediately remove the British troops from Boston after the Boston Massacre.

Samuel Adams died at the age of 81 on October 2, 1803, and was interred at the Granary Burying Ground in Boston. The city’s Republican newspaper, the Independent Chronicle, eulogized him as the Father of the American Revolution.

Elizabeth Wells Adams died in 1808.

Samuel Adams Quotation:

If ye love wealth greater than liberty, the tranquility of servitude greater than the animating contest for freedom, go home from us in peace. We seek not your counsel, nor your arms. Crouch down and lick the hand that feeds you; May your chains set lightly upon you, and may posterity forget that ye were our countrymen.

~ From a speech delivered at the State House in Philadelphia on August 1, 1776.

SOURCES

The Tea Act

Samuel Adams

Elizabeth Wells Adams

New World Encyclopedia

Samuel Adams Biography

Wikipedia: Samuel Adams

Elizabeth Checkley Adams

The Rights of the Colonists