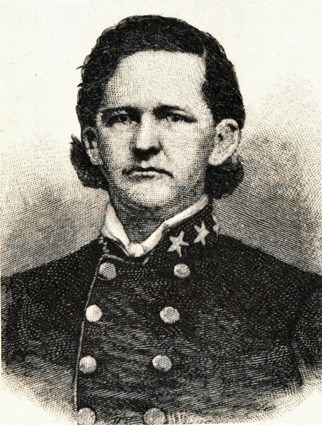

Wife of General Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb

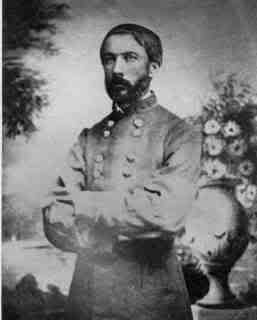

Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb was born April 10, 1823. at Cherry Hill, the family plantation in Jefferson County, Georgia. His parents were John and Sarah Rootes Cobb, who were married at Fredericksburg, Virginia. His family moved to Athens, Georgia, while he was still a child, and he lived there for the rest of his life.

Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb

Confederate Politician

Brigadier General in the Confederate Army

Horace Bradley, Artist

Thomas R. R. Cobb graduated from the University of Georgia first in his class in 1841, studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1842. During the 1840s and 1850s, Cobb and his older brother Howell Cobb – future Congressman and Secretary of the Treasury under President James Buchanan – campaigned against northern and southern radicals whose ideas threatened the Union. While Howell, an influential Democrat, served as Thomas’ political mentor, the younger Cobb focused most of his energies on furthering his brother’s career.

In 1844 Thomas Cobb married Marion Lumpkin, who was the daughter of the Supreme Court of Georgia Chief Justice Joseph Henry Lumpkin. They had three daughters who lived past childhood: Callender (Callie) who married prominent Athens educator Augustus Longstreet Hull; Sarah (Sally) who married Henry Jackson, son of CSA Brigadier General Henry Rootes Jackson of Savannah; and Marion (Birdie), who married prominent Georgia publisher and politician Michael Hoke Smith.

Early in his career Cobb developed a reputation as a talented constitutional lawyer with a great capacity for work. He was assistant secretary to the Georgia Senate during the late 1840s.

From 1849 to 1857 he served as reporter for the Georgia Supreme Court. While serving in this capacity he published several well-respected legal works, notably The Digest of the Statute Laws of the State of Georgia (1851), a supplement to the state’s existing code of laws and a substantial part of the Code of the State of Georgia (1861), and 20 volumes of Georgia Supreme Court reports.

Cobb was an ardent secessionist, and contributing to newspapers in support of the movement. He is best known for his treatises on the law of slavery titled An Inquiry into the Law of Negro Slavery in the United States of America (1858) and A Historical Sketch of Slavery From the Earliest Periods (1859).

Most of his proslavery defense was discredited after the Civil War.

Cobb was a deeply religious man and a leader in the Presbyterian church in Athens. His legal views reflected his puritanical religious beliefs and a desire for restraint and self-control. He supported prohibition of alcohol and prostitution, and advocated forced marriage for couples caught engaging in premarital sex.

Cobb’s was also motivated to improve educational opportunities. In 1854 his sister, Laura Cobb Rutherford, appealed for a female high school in Athens, and he responded by raising money and organizing a group of trustees to form the Athens Female High School. The school opened in January 1859 and was soon renamed the Lucy Cobb Institute in honor of Cobb’s eldest daughter, who died of fever at age thirteen in 1858.

Cobb was instrumental in reorganizing and expanding the University of Georgia. In 1859 he established the Lumpkin Law School with the aid of his father-in-law, Joseph Henry Lumpkin, a state supreme court justice for whom the school was named.

During the late 1850s, his brother Howell urged loyalty to the Union and compromise on slavery, but after the election of President Abraham Lincoln in 1860, T.R.R. Cobb renounced his Unionist leanings. On November 12, 1860, he delivered a speech in support of immediate secession before the state legislature. He believed that the Republican victory would shift the balance of power to the North, reducing the South to a powerless minority incapable of defending both slavery and its way of life.

After Georgia seceded from the Union on January 19, 1861, Cobb was elected to the Provincial Congress of the Confederate States of America in Montgomery, Alabama, and served on the committee that drafted the Confederate Constitution. The original manuscript is believed to be in his handwriting.

T.R.R. Cobb in the Civil War

Discouraged by what he considered to be a lack of cooperation, Cobb resigned from the Confederate Congress. Though lacking military experience, in August 1861 he formed a regiment of infantry, cavalry and artillery, known as Cobb’s Legion. Commissioned as a colonel, Cobb led his regiment into battles at Seven Days, Second Manassas, and Antietam, where it took heavy losses. He stated that he had lost “the flower of my battalion.”

He became unreasonably frustrated with his advancement through the ranks of command and felt that President Jefferson Davis, General Robert E. Lee and others were discriminating against him. Lee promoted Cobb to brigadier general on November 1, 1862, and assigned him command of his brother Howell’s old brigade.

The Confederate army reached Fredericksburg, Virginia, in late November 1862. Cobb’s brigade initially took a position near Howison Hill. He recognized the strength of the position and hoped ardently that the Federals would be foolish enough to attack it. The town was located on the west side of the Rappahannock River, while the Union Army was on the eastern shore – with only one narrow bridge connecting the two.

Cobb’s only regret was that a Union crossing near Fredericksburg would inevitably lead to the destruction of the town. “If they attempt it,” he wrote to his wife Marion, “poor old Fredericksburg is a doomed city and will be reduced to ashes as we shall be forced to destroy it before leaving it in their hands.”

Cobb was fond of Fredericksburg – his mother had grown up at Federal Hill, a house on the outskirts of town, and his parents were married there. The thought that Yankees might destroy his mother’s former home so infuriated him that he advised Lee “to raise the black flag and give no quarter to any scoundrel that crosses the river.”

As days passed without any movement on the part of the Union army, Cobb began to lose hope that the enemy would cross the river before spring. As late as December 10, he wrote his wife that he did not anticipate a battle at Fredericksburg, at least not in the near future. Instead, he thought the Federals would spend the winter gathering their strength for a major effort in the spring.

Regardless of what happened, Cobb promised his wife he would be careful. “Do not be uneasy about my being ‘rash,'” he told her. “The bubble of reputation cannot drag me into folly. God helping me, I hope to do my duty when called upon, trusting the consequences to Him.”

The day after Cobb wrote this letter, the Union army began laying pontoon bridges across the river. The following day, December 12, thousands of Union soldiers poured across the river and occupied the town.

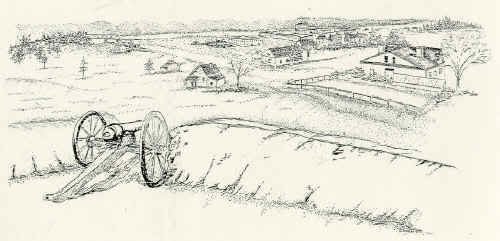

General Lafayette McLaws ordered Cobb to move his brigade up to Marye’s Heights above the town, which was fronted by a wide-open plain with few trees and houses from which to gain shelter, but with fences and a small canal that slowed the Union troops’ movements.

As the battle began on December 13, 1862, Cobb’s Georgia Brigade occupied a sunken road that ran along the foot of the ridge on the heights. A four-foot-tall stone wall that bordered the lane provided his Georgians with a strong ready-made trench. Besides the terrain, the Union advance was also hindered by incessant artillery fire coming from Confederate batteries on the heights.

The Union army’s frontal assaults that day against entrenched Confederate defenders on the heights was one of the most one-sided battles of the Civil War, with Union casualties more than twice as heavy as those suffered by the Confederates. Brigade after brigade of Yankees attacked but none of them reached the wall.

Between attacks, the Union army pounded Marye’s Heights with artillery. Cobb was standing in the road, adjacent to his headquarters at the Stephens House, when a Union shell came crashing through the dwelling. As it exited the building the shell exploded, wounding Cobb and killing two others.

General Cobb was mortally wounded when a piece of shrapnel from the shell severed his femoral artery. Members of Cobb’s staff quickly made a tourniquet in an effort to stanch the flow, then carried him to a field hospital. Doctors struggled to save the general’s life, but he quickly bled to death.

General Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb died on December 13, 1862. He is buried at Oconee Hill Cemetery in Athens, Georgia.

The Stephens House

During the Battle of Fredericksburg this house was used as a headquarters by General Thomas Cobb. He was standing in the road near the house when he was mortally wounded on December 13, 1862.

The T.R.R. Cobb House, where Thomas and Marion Cobb lived in Athens, Georgia, is now a house museum. It was moved from Stone Mountain, Georgia, where it had been moved a number of years before. Stone Mountain Park had hoped to restore the house, but the project fell through. The house had been partially restored to the way it looked when Thomas Cobb and Marion Cobb lived there.

SOURCES

Cobb’s Legion: Thomas R. R. Cobb

Wikipedia: Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb

New Georgia Encyclopedia: Thomas R. R. Cobb

Frederickburg.com: Cobb Gives His Life for the Confederacy