Wife of Confederate General William Mahone

Otelia Butler was born on August 1, 1835, Otelia Butler was the daughter of Dr. Robert Butler of the town of Smithfield in Isle of Wight County, Virginia, and his second wife, Otelia Voinard, from Petersburg, Virginia. The Butler family was prominent, and Dr. Butler was serving as the Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Virginia when he died in 1853.

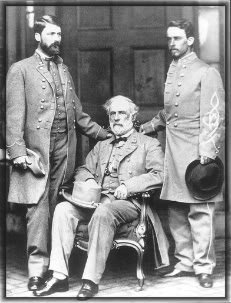

General William Mahone

William Mahone was born on December 1, 1826, in Southampton County, Virginia, in the tiny community of Monroe, which was located on the Nottoway River in an area of large plantations. The river was an important transportation artery in the years before railroads served the area.

William was nearly five years of age when the Nat Turner insurrection occurred in Southampton County. His father was then Lieutenant Colonel of the Southampton militia, and therefore played an important part in the overthrow of the insurrection.

In 1840, when William was 14 years old, the family moved about eight miles south to Jerusalem (now Courtland), where William’s father, Fielding Mahone, purchased and operated a tavern across from the county courthouse. According to his biographer, Nelson Blake, the freckled-faced youth gained a reputation in the small town for both “gambling and a prolific use of tobacco and profanity.”

William received his primary education from a country schoolmaster and learned mathematics from his father. When he was fifteen, he entered the Littletown Academy in Sussex County, where he was a student for two years.

In 1844, he was appointed a State Cadet at the recently opened Virginia Military Institute in Lexington Virginia. There he studied under Commandant William Gilham and Professor Thomas J. Jackson, who later earned the nickname Stonewall. Mahone graduated from VMI in 1847 with a degree in civil engineering, ranking 8th in a class of 12.

From 1848 to1849, Mahone was a teacher at the Rappahonnock Academy in Caroline County, Virginia, but was actively seeking an entry into civil engineering.

From 1851 to 1861, he pursued his fascination for the railroad. He helped build the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, an 88-mile line between Gordonsville and Alexandria, Virginia. Having performed that job well, he was hired to build a plank road between Fredericksburg and Gordonsville.

In 1853, Mahone was hired as chief engineer to build the new Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad (N&P). His innovative 12 mile-long roadbed through the Great Dismal Swamp between Norfolk and Suffolk employed a log foundation laid at right angles beneath the surface of the swamp. Still in use 160 years later, Mahone’s corduroy design withstands immense tonnages of modern coal traffic.

Mahone also engineered and built the 52 mile-long tangent track between Suffolk and Petersburg, which passed through Isle of Wight County, near Otelia Butler’s home in Smithfield. With no curves, it is a major artery of modern Norfolk Southern rail traffic.

Otelia Butler married William Mahone on February 8, 1855, and they settled in Norfolk, Virginia. Later in 1855, they escaped the yellow fever epidemic, which decimated a third of the population of the Norfolk-Portsmouth area, by staying with his mother in Jerusalem. Otelia and William had thirteen children, but only three survived to adulthood, sons William and Robert, and a daughter, also named Otelia.

The Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad was completed in 1858. Full of restless energy, Mahone’s rise was swift – in 1859, at the age of thirty-three he was named the president, chief engineer, and superintendent of the new Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad.

Legend has it that Otelia and William traveled along the newly completed 52-mile tangent line of the N&P, which passed through Isle of Wight, Southampton, and Sussex Counties, naming stations along the way. Otelia chose the names from Ivanhoe, a novel written by Sir Walter Scott – Waverly, Windsor, Wakefield, and Ivor. When they reached a point in Prince George County, the two could not agree on a name. It is said that they invented a new word in honor of their “dispute,” which is how the tiny community of Disputanta was named.

The Civil War

During the American Civil War, William Mahone became a Confederate Major General, and Otelia worked as a nurse in Richmond for several years. Mahone accepted a commission as colonel of the 6th Virginia Infantry Regiment in the Army of Northern Virginia. He commanded the Confederate’s Norfolk district until its evacuation, and was promoted to Brigadier General in November 1861.

In May 1862, during the Peninsula Campaign, he helped build the defenses of Richmond on the James River around Drewry’s Bluff. A short time later, he led his brigade at the Battles of Seven Pines and Malvern Hill.

Mahone led his brigade next at Second Bull Run in August 1862, where he took part in Longstreet’s assault. At the moment of truth, however, when his brigade was poised to make the final attack on the crumbling Federal line, Mahone hesitated to deliver the blow. He was wounded by a bullet in the chest; he was taken from the field and remained absent from the army throughout September and October.

Small of stature at 5 feet 5 inches tall and weighing only 100 pounds, Mahone was nicknamed Little Billy. Otelia was notified by Governor John Letcher that her husband had been injured in the Second Battle of Manassas, but had only received a “flesh wound.” She replied, “Now I know it is serious for William has no flesh whatsoever.”

Although his wound at Manassas had not been serious, Mahone suffered from acute dyspepsia (poor digestion) all of his life. He could only eat tea, crackers, eggs, and fresh milk. During the War, a cow and chickens accompanied him in order to provide dairy products. Whether it was from his poor digestion or the other way around, he was always extremely irritable.

Mahone wore his hair long, his eyes were blue beneath bushy brows. He had a dainty straight nose, and the lower half of his face was covered by a drooping brown mustache and long beard that touched his chest. His voice was high and piping, like a falsetto tenor.

Mahone was not a popular general; many of his men thought he was a tyrant. He was always a bundle of nervous energy, and subordinates gave him a wide berth out of respect for his quick temper and famous cussing fits.

Mahone at Gettysburg

On July 2, 1863, as part of General Richard Anderson’s division, Mahone marched forward along the Chambersburg Pike and filed south along Seminary Ridge before noon. There his Virginians were posted on the far left of Anderson’s division, facing east from McMillan’s Woods.

That day, the army’s assault started with General James Longstreet’s corps attacking toward the Round Tops in the late afternoon, and was taken up by Anderson’s division about 6:00 PM. When his turn came to strike, General Mahone refused to participate in the division’s attack on Cemetery Ridge.

General Anderson sent an aide to Mahone with orders to advance, but Mahone did not. To justify his inaction and insubordination in the face of a direct order, Mahone stated that Anderson had ordered him to stay put. Mahone’s men never moved, and the grand assault of the Army of Northern Virginia died on his front.

The following day, July 3, when Lee was scouring the army for every available man healthy enough to carry a musket, Mahone’s brigade, one of the freshest in the army, was assigned to protect artillery positions during Pickett’s Charge. Neither Lee nor General A.P. Hill nor Anderson mention this oversight in his report. Mahone lost 102 out of 1538 men at Gettysburg. Many Confederate brigades lost a third to a half their number in that catastrophic battle.

Mahone’s Gettysburg Report:

The operations of this brigade in the battle of Gettysburg, Pa., may be summed up in a few brief remarks. The brigade took no special or active part in the actions of that battle beyond that which fell to the lot of its line of skirmishers. During the days and nights of July 2 and 3, the brigade was posted in line of battle immediately in front of the enemy, and in support of Pegram’s batteries.

In this front, its skirmishers were quite constantly engaged and inflicted much loss upon the enemy, and after the repulse of our troops on the 3rd, maintained firmly its line. During the 2nd and 3rd, the brigade was exposed to a large share of the terrific shelling of those days, and from which its loss was mainly sustained. Casualties in the battle: Killed, 8 men; wounded, 2 officers and 53 men; missing, 39 men; total, 102.

Probably because he was one of only five brigadiers in Lee’s army who had held that rank for a full year, Mahone’s career did not suffer from his refusal to commit his brigade in the army’s most crucial battle.

The next year, after some of his men accidentally wounded General James Longstreet in the Battle of the Wilderness, Mahone was raised to division command when Anderson assumed Longstreet’s position. He was made major general on July 30, 1864, and served much more ably as a division commander than he ever had as a brigadier. (Mahone had campaigned for the rank of major general the previous year, but there was no opening available at that time.) By the end of the war, Mahone was Lee’s most conspicuous division leader.

Otelia and the children moved to Petersburg to be near General Mahone during the final campaign of the War in 1864-65 as Grant moved against Petersburg, seeking to sever the rail lines supplying the Confederate capital of Richmond.

Mahone at Petersburg

In early June 1864, the Union Army laid siege to Petersburg, Virginia, just south of Richmond, the Confederate capital. General Ulysses S. Grant wanted to defeat Lee’s army without resorting to a lengthy siege—his experience at Vicksburg told him that such affairs were expensive and difficult on the morale of his men.

Lt. Colonel Henry Pleasants, commanding the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry of General Ambrose Burnside’s’s IX Corps, made a novel proposal to solve Grant’s problem. Pleasants, a mining engineer in civilian life, proposed digging a long mine shaft underneath the Confederate lines and planting explosive charges directly underneath a fort in the middle of the Confederate First Corps line. If successful, Union troops could drive through the resulting gap in the line into the Confederate rear area, breaking the stalemate and winning the battle.

Digging began in late June 1864, creating a mine in a “T” shape with an approach shaft 511 feet. At its end, a perpendicular gallery of 75 feet extended in both directions. The Federals filled the mine with 320 kegs of gunpowder, totaling 8000 pounds, approximately 20 feet beneath the Confederate works, and the T gap, the side galleries, and the main gallery were packed with earth to prevent the explosion blasting out the mouth of the mine. On July 28, the mine was armed.

On the morning of July 30, 1864, Pleasants lit the fuse. But Pleasants had been given poor quality fuse. After no explosion occurred at the expected time, two volunteers from the 48th Regiment crawled into the tunnel. After discovering the fuse had burned out, they spliced on a length of new fuse and relit it.

Finally, at 4:44 a.m., the charges exploded in a massive shower of earth, men, and guns. Nine companies of the 19th and 22nd South Carolina were rocketed up into the air. A crater was created – 170 feet long, 60 to 80 feet wide and 30 feet deep. Between 250 and 350 Confederate soldiers were killed instantly in the blast.

After the dust had settled, the Union troops poured into the crater, while the Confederates under General Mahone, gathered as many troops together as they could for a counterattack. In about an hour’s time, they had formed up around the crater and began firing rifles and artillery down into it. For the next few hours, they slaughtered the Union soldiers in the crater as they attempted to escape, in what Mahone later described as a “turkey shoot.”

Some Union troops eventually advanced beyond the Crater to the earthworks and assaulted the Confederate lines, driving the Confederates back for several hours in hand-to-hand combat. When the shooting was over, General Mahone’s troops had pushed the Union forces back inflicting 3798 losses compared to the Confederates’ nearly 1500 men. What had begun as an innovative initiative turned into a terrible loss for the Union.

The quick and effective action led by Mahone was a rare cause for celebration by the occupants of Petersburg, embattled citizens and weary troops alike. “Little Billy” Mahone was promoted to Major General on July 1864 for his performance at the Battle of the Crater.

Recapture the Crater

Henry Kidd, Artist

Battle of the Crater

Petersburg, Virginia

However, Grant’s strategy at Petersburg eventually succeeded as the last rail line from the south to supply Richmond was severed in early April 1865. Mahone was with General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia for the surrender at Appomattox a week later.

After the war, William Mahone became the driving force in the linkage of the Norfolk and Petersburg, South Side, and Virginia and Tennessee Railroads. He was president of all three by the end of 1867. During the post-war Reconstruction period, he worked diligently lobbying the Virginia General Assembly for the legislation necessary to connect the three.

He successfully united them in 1870 to form the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad (AM&O), a new line comprising the three railroads he headed, extending 408 miles from Norfolk to Bristol, Virginia, in 1870. The Mahones moved to Lynchburg, Virginia, headquarters of the AM & O.

The Financial Panic of 1873 put the AM&O into conflict with its bondholders in England and Scotland. After several years of operating under receiverships, Mahone’s relationship with the creditors soured, and an alternate receiver was appointed to oversee the AM&O’s finances.

Mahone still worked to regain control, but his role as a railroad builder ended in 1881, when Philadelphia-based interests outbid him and purchased the AM&O at auction, renaming it the Norfolk and Western.

Mahone then turned his attention to politics, and he helped form and lead a coalition of blacks, Republicans, and Conservative Democrats that became known as the Readjuster Party.

Part of the AM&O Railroad had been owned by the state of Virginia. Working with black members of the Readjuster Party, Mahone helped arrange for a portion of the proceeds to be used to fund a teacher’s school and a collegiate institute to educate Virginia’s large black population, now known as Virginia State University, and also to build a mental hospital for blacks nearby, long known as Central State Hospital.

Although the Mahone family had owned several slaves before the war, Mahone accorded African Americans considerably more respect than many of his peers. Still, many African American leaders complained that Mahone was relegating them to the lower rung political positions, and he was affected by public sentiments against African Americans. To elevate them could diminish his white support, and he needed both public and white support.

Mahone subsequently won a term as a U.S. Senator. With his status as an independent, he held an important swing vote in the evenly divided upper house in the U.S. Congress. However, he tended to caucus with the Republicans, and was defeated for reelection by Virginia’s Conservative Democrats.

Mahone accumulated substantial wealth, partially through the foresight of valuable personal investments. He personally retained his ownership of land investments which were linked to the N&W’s development of the rich coal fields of western Virginia and southern West Virginia.

The Mahones moved back to Petersburg in 1873, where they lived the rest of their lives. Their first home on South Sycamore Street in Petersburg became part of the Petersburg Public Library. In 1874, they bought and enlarged a house on South Market Street which was their home thereafter.

Although out of office, the seemingly tireless Mahone continued to stay involved in Virginia politics until he suffered a catastrophic stroke in Washington DC, in the fall of 1895, and died a week later.

General William Mahone died on October 8, 1895, at the age of sixty-eight. Otelia lived as a widow in Petersburg for many years after his death.

Otelia Butler Mahone died on February 11, 1911, at the age of seventy-five.

SOURCES

Otelia B. Mahone

Siege of Petersburg

The 12th Virginia Infantry

The Old Dominion Brigade

Wikipedia: William Mahone

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Brigadier General William Mahone

The photo is John Bell Hood, not Mahone