Largest City in the Confederate States of America

New Orleans and its vital port became a major source of armament, supplies, and income to the Confederate Army. Its location near the mouth of the Mississippi River made the city an important and early target of the Union Army, which occupied the city for much of the war. New Orleans provided several leading officers and generals, including P.G.T. Beauregard and Harry T. Hays.

By Mauritz Frederick Hendrick de Haas

The USS Hartford leads the Union fleet up the Mississippi during the Battle of New Orleans.

Civil War Comes to New Orleans

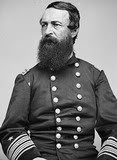

Late in 1861, Union authorities decided to send a flotilla of ships up the Mississippi River from New Orleans to meet the General Ulysses S. Grant‘s Union Army which was driving down the Mississippi valley behind a spearhead of armored gunboats. In mid-March 1862 Commander David Dixon Porter‘s flotilla of mortar schooners arrived.

Confederate officials believed the primary threat to New Orleans would come from the north, and made their defensive preparations accordingly. However, as Grant made some gains in the western theater, much of the city’s military equipment and manpower was sent upriver to stem the Union tide, leaving New Orleans no means to defend itself.

Fall of New Orleans

On April 16, 1862, the Union’s West Gulf Blockading Squadron under Admiral David Farragut pulled into position below Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip, the only forts guarding the city to the south. The gunboats Pinola and Itasca finally opened a small gap in the line of obstructions left by the enemy on the night of April 23. After a severe conflict with the forts and Rebel ironclads, at 2 o’clock on the morning of April 24, almost all of the Union fleet was able to pass.

When the Union fleet neared the city docks on April 28, Farragut sent Mayor John Monroe a note demanding “the unqualified surrender of the city.” The following day Farragut informed Monroe that New Orleans was now under Union control, and then sent a Marine detachment with two howitzers ashore to remove the Louisiana secession flag from the roof of the customs house.

The Union fleet had captured New Orleans without a battle in the city proper; thereby saving it from the destruction suffered by other cities in the American South. The following telegraph was forwarded to Union Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton:

I have the honor to announce that, in the providence of God, which smiles upon a just cause, the squadron under Flag Officer Farragut has been vouchsafed a glorious victory and triumph in the capture of New Orleans, Forts Jackson, St. Philip, Lexington, and Pike, the batteries above and below New Orleans, as well as the total destruction of the enemy’s gunboats, steam-rams, floating batteries (iron-clad), fire-rafts, obstruction booms, and chains. The enemy with their own hands destroyed from eight to ten millions of cotton and shipping. Our loss is 36 killed, and 123 wounded. The enemy lost from 1000 to 1500, besides several hundred prisoners. The way is clear, and the rebel defenses destroyed from the Gulf to Baton Rouge, and probably to Memphis. Our flag waves triumphantly over them all.

New Orleans Under the Union Army

Union troops under General Benjamin F. Butler occupied New Orleans on May 1, 1862, and issued General Orders No. 15, in which he forbade any plundering of public or private property. To the citizens, he declared martial law: imposing himself as the head of the government, “until the restoration of the United States authority. … All persons in arms against the United States are required to surrender themselves, their arms, equipments, and munitions of war.”

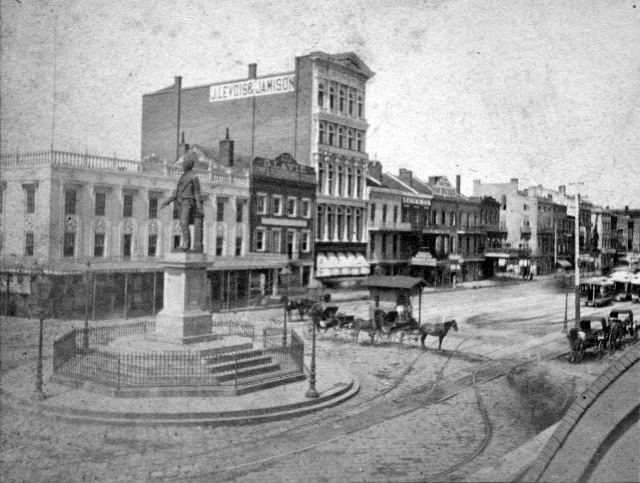

Image: Canal Street in Union Occupied New Orleans

Statue of Henry Clay in the foreground

Women of Civil War New Orleans

Butler demanded that all citizens must take an oath of allegiance to the Union, and the ladies of New Orleans immediately showed their distaste for the occupation forces. The women crossed the street to avoid greeting the Union men or passing under a Union flag, but their worst offense was spitting on the soldiers as they encountered them on the street. After two weeks of such treatment, Butler issued his infamous General Order No. 28:

As the officers and soldiers of the United States have been subject to repeated insults from the women (calling themselves ladies) of New Orleans in return for the most scrupulous non-interference and courtesy on our part, it is ordered that hereafter when any female shall by word, gesture, or movement insult or show contempt for any officer or soldier of the United States, she shall be regarded and held liable to be treated as a woman of the town plying her avocation [a prostitute].

This order provoked protests throughout the country and abroad, particularly in England and France. The locals nicknamed Butler The Beast; across the pond the London Review called him an uncivilized dictator:

If he had possessed any of the honourable feeling which is usually associated with a soldier’s profession, he would not have made war on women. If he had even been endowed with the ordinary magnanimity of a Red Indian, his revenge would have been satiated before now. It required not only the nature of a … pitiful kind of savage … to inflict an imprisonment so degrading in its character … accompanied by privations so cruel. … It is only a pity that so unadulterated a barbarian should have got hold of an Anglo-Saxon name.

Southern women were highly offended by the order. Catherine Devereux Edmondston referred to it in her diary as “cold-blooded barbarity.” Clara Solomon, a 17-year-old Jewish girl, expressed similar feelings, asking, “what anyway could a woman’s taunts do to [the Union soldiers].” New Orleans Mayor John Monroe refused to enact the order, and Butler quickly imprisoned him.

General Butler defended his actions in a letter, claiming “the devil had entered the hearts of the women of [New Orleans].” He argued that it restored order and prevented the violence that may have erupted if the insults had continued:

After that order, every man of my command was bound in honor not to notice any of the acts of these women. … What has been the result? Since that order, no man or woman has insulted a soldier of mine in New Orleans, and from the first hour of our landing no woman has complained of the conduct of my soldiers toward her, nor has there been a single cause of complaint.

Women Banished to Ship Island

In 1862 Eugenia Levy Phillips and her lawyer husband moved from Washington DC to New Orleans. Beast Butler accused Eugenia of laughing during a Union officer’s funeral procession. He arrested her and banished her to mosquito-infested Ship Island in the Gulf of Mexico, more than sixty miles from New Orleans. Eugenia responded that the island, “has one advantage over the city, sir; you [Butler] will not be there.” She served more than three months before returning to New Orleans, where cheering crowds welcomed her home.

In July 1862, Anne Larue wore Confederate colors and a secession badge, setting off a near-riot. Union troops arrested Larue. When Butler asked her why she had behaved in such a treasonous manner, she replied that “she felt very patriotic that day.” Butler sentenced Larue to two years at Ship Island, but she was released after only three weeks.

Butler Banished from New Orleans

Butler’s tactics worked to some extent, but not for long. Although very few New Orleans women continued to be politically active after Phillips and Larue were arrested, opposition to Butler’s methods mounted. In November 1862 President Lincoln appointed General Nathaniel Banks to command the Army of the Gulf. In December Banks sailed from New York to replace Butler. Despite his disappointment, Butler welcomed Banks to New Orleans on December 17, 1862 and briefed him on civil and military affairs.

Image: Union Navy ships capture New Orleans in April 1862, by Xanthus Smith

The people of New Orleans were overjoyed at Butler’s departure. One woman stated, “You may reach Yankeedom in safety – but remember, vile old coward, that day will come when you will be hunted down like a fox in your den, and retribution will surely fall upon you.” Confederate President Jefferson Davis, declared Butler “a felon, deserving of capital punishment” and issued an order stating that any officer who caught Butler should hang him immediately.

On December 24, Butler delivered farewell address to the people of New Orleans:

The enemies of my country, unrepentant and implacable, I have treated with merited severity. I hold that rebellion is treason, and treason persisted in is death, and any punishment short of that due a traitor gives so much clear gain to him from clemency from the Government.

General Banks softened some of Butler’s more controversial policies in an attempt to win Confederate support. Suppressed churches were reopened and the confiscation and sale of Confederate property was stopped.

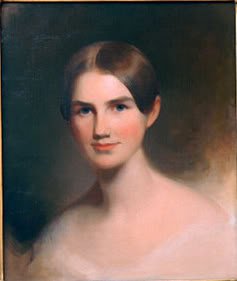

Mary Theodosia Palmer Banks joined her husband in New Orleans and held lavish dinner parties for the Union soldiers and their families. She produced concerts and plays as well; on April 12, 1864, she played the role of the “Goddess of Liberty” surrounded by all of the states of the reunited country.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Butler’s General Order No. 28

Wikipedia: New Orleans in the American Civil War

Historynet: The Beast Turned Loose in New Orleans

The “ladies” were not just spitting and sneering, they hurled the cntents of theeir chamber pots out windows at Union troops and officers, including David Farragut. It pput the eneral order in a slightly different light if you consider that these “adies” were hurling urine and feces at other people.