Wife of British General Thomas Gage

By John Singleton Copley

Margaret began to sit for Copley within three days of his arrival in New York City in 1771. She is depicted wearing an iridescent caftan over a lace trimmed chemise with a jeweled brooch and an embroidered belt. Pearls and a turban-like swath of drapery adorn her hair. Her sleeves are held up with ropes of pearls and her hair is wrapped in a length of green silk fashioned as a turban. Her languid and informal pose, shockingly different from the upright posture of Copley’s Boston sitters, underscores the sensuality of the image.

Margaret Kemble was born into a well-known family in East Brunswick, New Jersey, in 1734. Her father, Peter Kemble, was a wealthy merchant and politician; her grandfather was Stephanus Van Cortlandt, the Mayor of New York. Margaret was related through her mother, Gertrude Bayard, to the Van Rensselaers, the de Lanceys, and other leading New York families. Her ethnic lineage included English, Greek, Dutch, and French ancestors, making her rather exotic for her day. She was considered a beautiful and intelligent woman.

Thomas Gage was born in Firle, England, the second son of the first Viscount Gage. In 1728, Gage began attending the prestigious Westminster School, where he met such figures as John Burgoyne, Richard Howe, Francis Bernard, and George Sackville. Upon graduation, Gage joined the British Army, first as an ensign, and was promoted to lieutenant colonel in March 1751. His regiment was sent to America in 1755.

In December 1757, Thomas Gage spent the winter in New Jersey, recruiting for the British army. While it is uncertain exactly when he met her, his choice of the Brunswick area may well have been motivated by his interest in Margaret Kemble, a well-known beauty of the area. By February 1758, Gage was in Albany, preparing for that year’s campaign.

On December 8, 1758, Margaret Kemble married Thomas Gage, the couple played a prominent role in New York society for more than 10 years. They were a happily married pair, and observers often remarked on the closeness of their relationship and the apparent strength of their marriage. Five daughters and six sons were to be born to the couple.

By the time of their marriage, Gage had become a brigadier general. In 1760, he was appointed military governor of Montreal, a task Gage found somewhat thankless. Margaret came to stay with him at Montreal, and their first two children, Henry and Maria Theresa, where born there.

In 1761, Gage was promoted to major general, and in 1762 he was placed in command of the Twenty-Second Regiment, which assured him a command even in peacetime. In October 1763, Gage was promoted to commander in chief of the British North American forces, a position he held from 1763 to 1775.

Gage immediately left Montreal, and took command in New York on November 17, 1763. He spent most of his time as commander-in-chief, the most powerful office in British America, in and around New York City. While Gage was clearly burdened by the administrative demands of managing a territory that spanned the entirety of North America east of the Mississippi River, the Gages clearly relished life in New York, actively participating in the social scene.

During Gage’s administration political tensions rose throughout the American colonies. As a result, Gage began withdrawing troops from the frontier to fortify urban centers like New York City and Boston. As the number of soldiers stationed in cities grew, the need to provide adequate food and housing for these troops became urgent. Parliament passed the Quartering Act of 1765, permitting British troops to be quartered in private residences.

In the fall of 1768, British troops landed in Boston and marched to Faneuil Hall, causing great unrest. To calm the citizenry, the king ordered General Gage to Boston. Events moved quickly after his arrival. The nonimportation movement cut imports from Britain by nearly half in 1769. Thomas Hutchinson succeeded Francis Bernard as governor of Massachusetts, and the local citizens found the British troops in Boston to reinforce Hutchinson’s authority increasingly hateful.

On March 5, 1770, taunts from an angry mob caused inexperienced British soldiers to fire on civilians. The incident was dramatized in a provocative and deliberately inaccurate print by Paul Revere that established the Boston Massacre as a symbol of British tyranny. That same year, Gage was promoted to lieutenant general. Late that year, he wrote

“America is a mere bully, from one end to the other, and the Bostonians by far the greatest bullies.”

Thomas and Margaret Gage and their ten children returned to England in June 1773, and settled at the family estate in Sussex. While in England, they missed the Boston Tea Party in December 1773. In the resulting controversy, British forces shut down Boston Harbor until the colonists had made reparations in full for every leaf of tea lost.

In 1774, the British Parliament passed a series of measures known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts, as a way to punish the colonies, and specifically the Province of Massachusetts Bay, for this and other acts of protest against British colonial policy. In May 1774, King George III sent Gage back to Boston, naming him military governor of Massachusetts, with hopes that Gage could restore order to the colony, and enforce the Parliamentary acts.

Margaret Gage arrived in Boston in late 1774, sometime after her husband’s arrival. Although Gage had initially been respected by the colonists, he was also regarded with a measure of suspicion. Margaret was anguished over the conflict in the colonies and her divided loyalties. She hoped that her husband would not cause a conflict resulting in the loss of the lives of her countrymen.

In September 1774, Gage ordered a mission to remove gunpowder from a magazine in what is now Somerville, MA. This action, while successful, caused a huge popular reaction known as the Powder Alarm that prevented Gage from successfully executing other raids. This was in large part due to Paul Revere and the Sons of Liberty. The Sons of Liberty kept careful watch over Gage’s activities after this point, and successfully warned others of future actions before Gage could mobilize his British regulars to execute them. Gage was criticized by his own men for allowing groups like the Sons of Liberty to exist.

By 1775, tensions between the American colonies and the British government had approached the breaking point, especially in Massachusetts, where Patriot leaders formed a shadow revolutionary government and trained militia to prepare for armed conflict with the British troops occupying Boston. General Gage received instructions from Great Britain to seize all stores of weapons and gunpowder accessible to the American insurgents.

Tory Spies

The Tories – Americans who were loyal to Britain – had spies who monitored the activities of the colonists. Margaret Gage’s brother, Major Stephen Kemble, was General Gage’s Chief Intelligence Officer. He obtained the services of Dr. Benjamin Church, a member of the Provincial Congress and Committee of Safety, who was secretly spying for the British – the doctor had an expensive mistress and spying brought ready cash.

Thus, while the Patriot Congress met in Concord (October, 1774, and March through April, 1775), sworn to secrecy, Dr. Church regularly provided summaries of the proceedings to Gage.

From Tory spies, General Gage learned that the Massachusetts militia were storing arms and ammunition in Concord, about 20 miles northwest of Boston. He also heard that Samuel Adams and John Hancock were in Lexington.

Patriot Spies

By early 1775, the Boston rebels under Dr. Joseph Warren had an elaborate spy network to monitor British military activities. He received intelligence about British troop movements on April 18; to verify this information, Warren relied on a confidential informant, who was well connected to the top levels of British command. The informant confirmed that the British planned to seize Samuel Adams and John Hancock at Lexington, and then destroy patriot military stores at nearby Concord.

Based on this information, Dr. Warren sent Paul Revere on his famous Midnight Ride through the Massachusetts countryside to warn the Patriot leaders and the townspeople of Lexington and Concord of the British plans. Warren was killed a few months later in the Battle of Bunker Hill, and the true identity of his informant may never be known.

The Shot Heard ‘Round the World

On the night of April 18, 1775, General Thomas Gage ordered 700 British regulars to arrest John Adams and John Hancock in Lexington, and to continue on to Concord and destroy the military supplies the colonists had stored there.

About 5 am on April 19, the Redcoats arrived at Lexington to find 77 armed Minutemen waiting for them on Lexington’s common green. They ordered the outnumbered Patriots to disperse, and after a moment’s hesitation, the Americans began to drift off the green. Suddenly, a shot was fired from an undetermined gun, and a cloud of musket smoke soon covered the green. When the brief Battle of Lexington ended, eight Americans lay dead and 10 others were wounded; only one British soldier was injured. The American Revolution had begun.

When the British troops reached Concord at about 7 am, they found themselves encircled by hundreds of armed Patriots. They managed to destroy the military supplies the Americans had collected, but were soon advanced against by a gang of Minutemen, who inflicted numerous casualties.

The commander of the British force ordered his men to return to Boston, without directly engaging the Americans. The militia had its revenge, killing several British soldiers as the Red Coats hastily marched through town. As they retraced their 16-mile journey, their lines were constantly beset by Patriot marksmen firing at them from behind trees, rocks, and stone walls. By the time the British reached the safety of Boston, nearly 300 British soldiers had been killed, wounded, or were missing in action. The Patriots suffered fewer than 100 casualties.

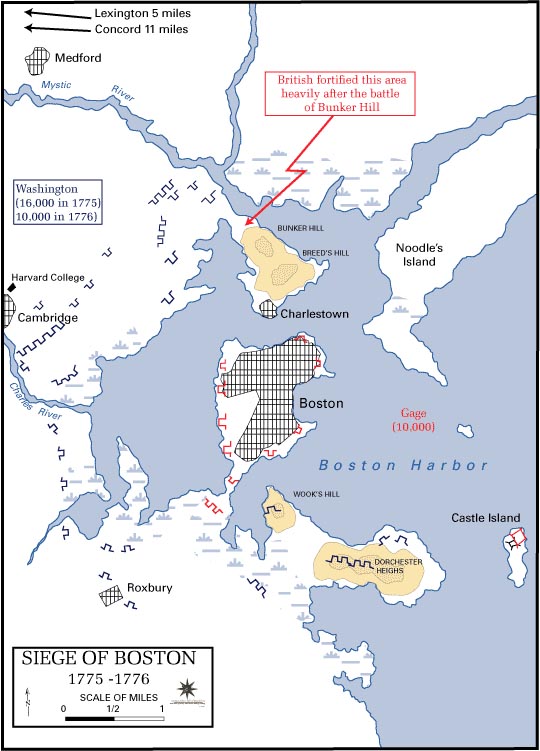

The Americans followed the British back to Boston, and occupied the neck of land extending to the peninsula the city stood on. This began the Siege of Boston. Initially, the 6,000 to 8,000 rebels (led mainly by General Artemus Ward) faced some 4,000 of General Gage’s British regulars, bottled up in the city. British Admiral Samuel Graves commanded the fleet that continued to control the harbor.

The British Army had failed to capture Hancock and Adams, and their search for weapons had been largely unsuccessful – the colonists had removed most of the supplies. They did destroy a small colonial arsenal and caused some damage to the town of Concord. No one doubted that the Patriots had received advance warning.

The warning had been sent days before the soldiers departed Boston. Because of this, General Thomas Gage was called into question, where he revealed he had told only one other person about the Concord march before revealing it to top officers. Many believed Gage had been betrayed by someone very close to him – his American-born wife, Margaret Kemble Gage.

In particular, Margaret supposedly warned Dr. Joseph Warren on April 18, 1775, that her husband’s troops planned to arrest the Patriot leaders at Lexington, and then raid the armories at Concord. Roxbury clergyman, William Gordon, wrote that Warren’s spy was

“a daughter of liberty unequally yoked in the point of politics.”

Several historical works have suggested that she was sympathetic to the colonial cause and may have supplied the rebels with military information. True, Margaret’s political sentiments were not always those of her husband, and she had long felt cruelly divided by the growing rift between Britain and America. One acquaintance noted that “she hoped her husband would never be the instrument of sacrificing the lives of her countrymen.”

There is no proof of her complicity, but Margaret was packed aboard a ship called the Charming Nancy and sent back to England, supposedly to “tend to the family estate.” The General remained in America for another long painful year. Thereafter, they were estranged, and their marriage deteriorated.

On May 25, Gage received about 4,500 reinforcements and three new Generals — Major General William Howe and Brigadiers John Burgoyne and Henry Clinton. With his new generals, Gage began to lay out a plan to break the grip of the besieging forces at Boston. They would use an amphibious assault to remove the Americans from the Dorchester Heights, or take their headquarters at Cambridge. To thwart these plans, General Artemus Ward gave orders to General Israel Putnam to fortify Bunker Hill.

On June 17, 1775, British forces under General Howe seized the Charlestown peninsula at the Battle of Bunker Hill. While they took their objective, they failed to break the siege. The Americans held the ground at the base of the peninsula. Gage called it, “A dear bought victory, another such would have ruined us.” British losses were so heavy that from this point, the siege essentially became a stalemate.

On June 25, 1775, Gage wrote a dispatch to England, notifying Lord Dartmouth of the results of the June 17 battle. This report repeated his earlier warnings that “a large army must at length be employed to reduce these people” and would require “the hiring of foreign troops.” Soon thereafter, Gage was recalled to England; he received the order in Boston on September 26, and sailed for England on October 11. Major General Howe replaced Gage as acting Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in the American colonies.

Thomas and Margaret Gage remained married, and settled into a house in London. While Thomas was presumably given a friendly reception in his interview with a sympathetic King George, the public and private writings about him and his fall from power were at times vicious. His health began to decline early in the 1780s.

General Thomas Gage died on the Isle of Portland on April 2, 1787, and was buried in the family plot at Firle.

Margaret Kemble Gage spent the second half of her life in England, and died at the age of 90 in 1824, surviving her husband by almost 37 years.

SOURCES

Thomas Gage

Women: Margaret Kemble Gage

Dictionary of Canadian Biography

Wikipedia: Margaret Kemble Gage

Hi, newer scholarship has come up about Mrs. Gage and put paid to the idea that she was unceremoniously shipped back to England and the marriage was over. This notion is a postwar American invention. She met him later that year, in October of 1775. He knew he was going to go back to Britain anyway, because of the debacle at Concord. Before that, not only Margaret Gage and his family left but also all the wives of the other British officers, since this was now a war zone. Furthermore, the Gages went on to have two more children, and they lived together at their estate until he died in 1787. Hardly a destroyed marriage. See: https://boston1775.blogspot.com/search?q=Gage

Hi…I’m in the midst of a novel about the unknown soldier buried in Lexington. My character is an orderly for General Gage and in that role works with Margaret Kemble. Different sources have her having seven, ten and eleven children. Can you help me substantiate how many please? Are there any biographies of Margaret. So far I have not located any.

Thank you for what ever help you can give me.

D-L Nelson