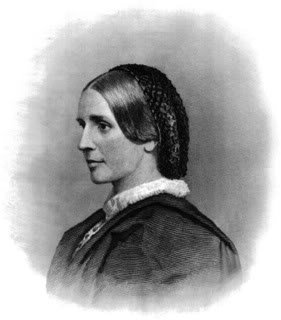

Adeline Blanchard Tyler, a Civil War nurse and hospital administrator, was born on December 8, 1805, in Massachusetts. Little is known of her early life, except that she married John Tyler in 1826, and they had no children.

Church Home and Hospital Marker

An Episcopalian Deaconess

After her husband’s death in 1853, Adeline became a deaconess of the Episcopal church, and traveled to Europe to take training as a nurse. Upon her return to Boston, she resumed her charitable activities in the role of deaconess and cared for the sick of her parish.

In the summer of 1856, she received a letter requesting her services for a small infirmary attached to St. Andrew’s Church in Baltimore, Maryland. It was the desire of Bishop Whittingham of that Diocese to establish there a Protestant Sisterhood similar to those already existing in Germany and England.

Mrs. Tyler was invited to become the superintendent of this order – a band of noble and devout women who wanted to devote their lives and talents to works of charity and mercy. Their mission was to care for the sick and to provide spiritual comfort.

Mrs. Tyler also administered the affairs of the Church Home, a charitable institution conducted by the sisterhood. Among other things, she devoted one day a week to visiting the Baltimore jail, at that time a crowded and squalid prison.

Church Home and Hospital was where Edgar Allan Poe died on October 7, 1849, and where many doctors were trained who served in the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War.

The American Civil War

Sister Tyler had been in Baltimore five years, tending to her various duties, when the storm that had so long threatened the land, burst forth in all its fury.

On April 15, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln issued his first proclamation, announcing the presence of rebellion, commanding the insurgents to lay down their arms within twenty days, and calling on the militia of the loyal states to provide seventy-five thousand men for the defense of their country. The order was promptly obeyed.

The Baltimore Riot

Immediately after the President’s call to arms, regiment after regiment was hurried forward for the protection of the Capitol, supposed to be the most vulnerable point. Among these was the Sixth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers.

On April 19th, this regiment was attacked by an angry mob in the streets of Baltimore, and several of its men were killed. This occurred on a Friday, the day Mrs. Tyler visited the jail. The news of the riot reached her as she was leaving home, and caused her to postpone her visit for several hours. When she finally went, she saw wounded men being conveyed to places where they might be cared for.

Concern for the fate of the men of her own home state, Adeline quickly concluded her duties at the jail, and sent a note to a friend, who summoned her to the Holliday Street police station. She sent for a carriage, and proceeded to the station house. By this time it was quite dark, and she was alone. She asked the driver to give her whatever aid she might need, and to come to her should he even see her beckon from a window, and he promised to do so.

She knocked at the door, and was assured that the worst cases had been sent to the infirmary, and that those who were in the upper room of the station house had been properly cared for, and were in bed for the night. She again asked to be allowed to see them, adding that the care of the suffering was her life work, and she would like to assure herself that they needed nothing. She was again denied.

“Very well,” she replied, “I am myself a Massachusetts woman, seeking to do good to the citizens of my own state. If not allowed to do so, I must send a telegram to Governor Andrews informing him that my request has been denied.” The police then admitted her.

Two soldiers were already dead. Two or three were in bed, and the rest lay in their misery upon stretchers. All the wounded had been drugged, and were either partially or entirely insensible to their miseries. Some eight or ten hours had elapsed since the wounds were received, but nothing had been done, except to stanch the blood by thrusting large pieces of cotton cloth into the wounds. Even their clothes had not been removed.

One of them had been shot in the hip. Another was injured in the back of the neck, apparently by a heavy glass bottle, because pieces of glass still remained in the wound. He lay in bed, still in his soldier’s overcoat, the rough collar of which was irritating the wound. These two were the most seriously hurt.

Mrs. Tyler, with the aid of her driver, obtained a covered furniture wagon and had the soldiers conveyed to the Church Home and Hospital. Here a surgeon was called, their wounds dressed, and she extended to them the care and kindness of a mother. In a month, they had recovered enough to return to Massachusetts.

For her efforts in behalf of the Massachusetts men, Sister Tyler received the personal acknowledgments of the Governor, the President of the Senate, and the Speaker of the House of Representatives of that state.

Camden Street Hospital

Soon thereafter, Mrs. Tyler helped establish a hospital in the National Hotel near Camden Station, but was asked to leave when she insisted that Confederate and Union wounded receive the same care. She then went to New York City to visit friends.

Chester Hospital

She hadn’t been in the city very long before she was urgently desired by the Surgeon-General to take charge of a large hospital at Chester, Pennsylvania, which had just been established and greatly needed the aid of women. She accepted the appointment, and went to Boston, where she selected from among her friends and others who offered their services, a corps of excellent nurses who accompanied her to Chester.

In this hospital, there was often from five hundred to one thousand sick and wounded men, and Mrs. Tyler made use of the ample stores and money supplied by her friends in the east for the use of her patients.

Naval School Hospital

She remained at Chester a year, and was then transferred to Annapolis, where she was placed in charge of the Naval School Hospital, remaining there until the latter part of May, 1864.

During that time, men from the prison pens of Andersonville and Belle Isle were brought there. Mrs. Tyler and her associates gave kind and tender care to these wretched men. Filth, disease, and starvation had done their work on these men. Emaciated, many of them too feeble for the least exertion, and their minds scarcely stronger than their bodies, they were indeed a spectacle to call for every effort of kindness.

In the spring of 1864, exhausted by her labors, Mrs. Tyler was obliged to send in her resignation. Her health seemed utterly broken down, and her physicians and friends saw an entire change of scenery as the best hope of her recovery. She had often been sick for some time, and her illness at last terminated in fever and chills. Her physicians advised a sea voyage as essential to her recovery.

European Journey

She left the Naval School Hospital on May, 27,1864, and set sail from New York on June 15th. The disease didn’t subside at once, and she endured extreme illness during her voyage. She was completely prostrate on her arrival in Paris, where she lay sick for three weeks before being able to travel by railroad to Switzerland to rejoin her sister. Mrs. Tyler spent about eighteen months in Europe, traveling over various parts of the Continent, and England, where she remained four or five months.

Home Again

She finally returned to her native land in November, 1865, to find the devastating war that had raged here at an end. Her health had been entirely restored, and she was happy in the belief that long years of usefulness yet remained to her.

Adaline Blanchard Tyler died in 1875.

SOURCES

Woman’s Work in the Civil War

Church Home and Hospital