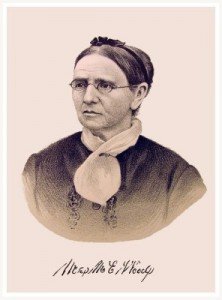

Among the heroic and devoted women who labored for the soldiers of the Union in the Civil War, and endured all the dangers and privations of hospital life, was Miss Melcenia Elliott of Iowa. Born in Indiana, and reared in the northern part of Iowa, she grew to womanhood amid the scenes and associations of country life, with a generous nature, superior physical health, and a heart warm with the love of country and humanity.

Her father was a prosperous farmer, and gave three of his sons to the struggle for the Union, who served honorably to the end of their enlistment, and one of them re-enlisted as a veteran, performing the perilous duties of a spy, that he might obtain valuable information to guide the movements of our forces.

The Civil War

At the beginning of the war, Melcenia was a student at Washington College in Iowa, an institution open to both sexes, and under the patronage of the United Presbyterian Church. But the organization of regiments composed of her friends and neighbors, and the enlistment of her brothers in the Union army of the Union fired her ardent soul with patriotism.

For many months, her thoughts were far more with the soldiers in the field than on her studies, and as soon as there was a demand for female nurses in the hospitals, she offered her services and was accepted.

During the summer and autumn of 1862, she was in the hospitals in Tennessee, ready on all occasions for the most difficult posts of service, ministering at the bedside of the sick and wounded, cheering them with her warm words of encouragement and sympathy and her pleasant smile.

In all hospital work, in the offices of nursing and watching, and giving of medicines, in the preparation of special diet, in the care and attention necessary to have the hospital beds clean and comfortable, and the wards in proper order, she was untiring and never gave way to weariness or failed in strength.

Memphis Hospitals

During the winter of 1862-63, she was a nurse at a hospital at Memphis, and rendered most useful and excellent service. In one of the hospitals, there was a sick soldier who came from her neighborhood in Iowa, whom she had known, and for whose family she felt a friendly interest. She often visited him in the sick ward where he was, and did what she could to alleviate his suffering, and to comfort him in his illness.

But gradually he became worse, and when he needed her sympathy and kind attention more than ever, the surgeon in charge issued an order that excluded all visitors from the wards, during those times when she could leave the hospital where she was on duty and visit her sick neighbor and friend.

The front entrance of the hospital was guarded, but she had too much resolution and too much kindness of heart to be thwarted in her good intentions. By scaling a high fence in the rear of the hospital, she could enter without being obstructed by guards. Aided by the nurses on duty in the ward, she made her visits in the evening to the sick man’s bedside until he died. It was his dying wish that his remains be carried home to his family, none of whom were present, and Melcenia undertook that difficult task.

Getting leave of absence from her own duties, without the needed funds for the trip, Melcenia made the journey alone, with the body in her charge – all the way from Memphis to Washington, Iowa, overcoming all difficulties of procuring transportation. By this act of heroism, she won the gratitude of many hearts, and gave comfort and satisfaction to the friends and relatives of the departed soldier.

Benton Barracks Hospital

Returning as far as St. Louis, she was transferred to the large military hospital at Benton Barracks and didn’t return to Memphis. Here for many months during 1863, she served faithfully, and was considered one of the most efficient and capable nurses in the hospital.

At Benton, she became associated with a band of noble young women, under the supervision of Miss Emily Parsons of Cambridge, Massachusetts, who had left her pleasant New England home to be at the head of the nursing department there. Warm friendships grew among these women, and Miss Parsons never ceased to regard with deep interest, the tall, determined girl, who never allowed any obstacle to stand between her and any useful service she could render to the defenders of her country.

During the summer of 1863, it became necessary to establish a ward for cases of erysipelas, a skin disease that was generating an unhealthy atmosphere. The surgeon in charge, instead of assigning a female nurse, called for a volunteer among the women nurses of the hospital.

There was naturally some hesitancy about taking so trying and dangerous a position, but Miss Elliott promptly offered her services. For several months she performed her duties in the erysipelas ward with the same concern for the welfare of the patients that had characterized her work in other positions.

The Refugee Home of St. Louis

Late in the fall of 1863, Miss Elliott yielded to the wishes of the Western Sanitary Commission, and became matron of the Refugee Home of St. Louis – a charitable institution that was designed to give shelter and assistance to poor families of refugees, mostly widows and children, who were constantly arriving from the exposed and desolated portions of Missouri, Arkansas, Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas.

They were sent north, often by military authority, as deck passengers on Government boats to get them away from the military posts in our possession further south. For a year, Miss Elliott managed the internal affairs of that institution with great efficiency and good judgment, under circumstances that were very trying.

Many of the refugees were of the class called the poor white trash of the South – filthy, ragged, proud, indolent, ill-mannered, given to the smoking and chewing of tobacco, often diseased, inefficient, and either unwilling or unable to conform to the necessary regulations of the Home, or to do their own proper share of the work of the household, and the keeping of their apartments clean and orderly.

It was a great trial of her Christian patience to see families of children of all ages, dirty, ragged, and ill-mannered, lounging in the halls and at the front door, and their mothers doing little better themselves, getting into disputes with each other, chewing or smoking tobacco, and leaving the necessary work allotted to them neglected and undone.

But out of this confusion Miss Elliott, by her efficiency and force of character, brought a good degree of cleanliness and order. Among other things, she established a school in the Home, gathered the children into it in the evening, taught them to spell, read and sing, and inspired them with a desire for knowledge.

At the end of a year of this work, Miss Elliott was called to the position of matron of the Soldiers’ Orphans’ Home, at Farmington, Iowa, which she filled for several months, with her usual efficiency and success. After long and arduous service for the soldiers, for the refugees, and for the orphans of our country’s defenders, she returned home to her family, and to the society and occupations for which she was preparing herself before the war.

SOURCE

Woman’s Work in the Civil War